Shout-outs and big ups

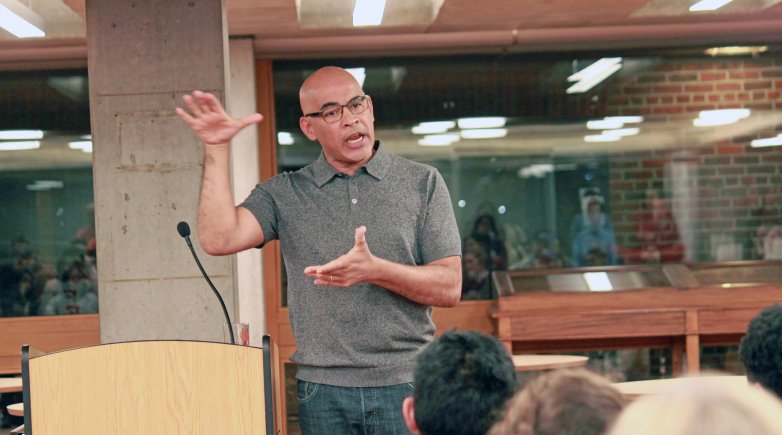

A conversation with poet and English Instructor Willie Perdomo.

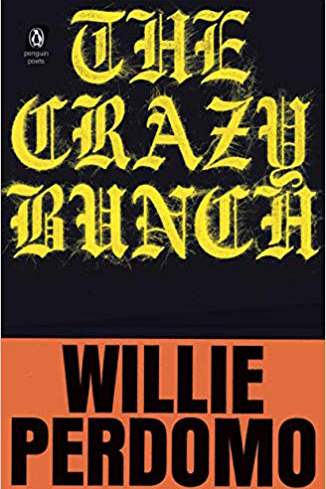

Willie Perdomo writes poetry like he’s laying down a song track. Verbs, adjectives, prepositions, nouns — these are the drumbeats, vocals, synths, guitars. In his fourth book, The Crazy Bunch, released this spring by Penguin, Perdomo’s dexterous poetic style practically break-dances off the page. Which makes sense, especially when you think of this collection as a soundtrack to the sweet and tragic summer his titular crew came of age in East Harlem in the early 1990s, just as rap and hip-hop music took hold of their neighborhood.

Perdomo is the author of the National Book Critics Circle Award finalist The Essential Hits of Shorty Bon Bon; the PEN/Open Book Award-winner Smoking Lovely; and Where a Nickel Costs a Dime, a finalist for the Poetry Society of America’s Norma Farber First Book Award. His writing has also appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Norton Anthology of Latino Literature, Poetry and African Voices.

Now in his sixth year as an instructor of English at the Academy, Perdomo continues to perfect his craft. We grabbed coffee with the poet just before he headed off to the Montalvo Arts Center in California, where he will complete a summer residency as a Lucas Artists Fellow.

Q: You introduce your collection with the quote "to be our own, to be electric, fresh... ." It’s a line Walt Whitman wrote in a letter to Ralph Waldo Emerson back in 1855. Why resurrect it here?

Willie Perdomo: That word "fresh," it stuck out for me. And then the idea of the expansiveness of the liberated new verse that Whitman was advocating. Laying claim to that part of what it means to live in a democracy where your language is not constrained by any kind of law.

Q: You mention the "Poetry Cops" over and over in Crazy Bunch. Who are they? Do they lay down the law for your poetry?

Perdomo: The cops are there to probe a little bit, trigger off the memory. Clearly the book, as much as it is about a weekend in the life of these young men and this crew at large, it’s also a book about writing poetry. There’s a body of folks who act as gatekeepers in these worlds, where they tell you what you can and can’t do in terms of writing. What’s shunned upon and what’s not. The cops represent that in many ways.

Q: As an English instructor, are you a poetry cop?

Perdomo: As a teacher, my approach is not a correctional approach that way, but I am thoroughly invested in providing you with the right skills so that you can get your line across, get the sentence building into the next paragraph, and that paragraph building into the next. The level of focus and concentration and intentionality that goes behind writing even 500 words, that’s what you look for.

Q: I had to look up a lot of words while reading your poems.

Q: I had to look up a lot of words while reading your poems.

Perdomo: When you get your proofs from the copy editor at the publishing house, they usually have a list of terms that they highlight. These are the terms that come up throughout the manuscript that they either researched or couldn’t find. I was in awe. It was five or six pages long, if I remember, and that’s when I knew I was in a good place. The language was that specific.

Q: It’s amazing that you could hold a vernacular note for that long and it doesn’t feel outdated.

Perdomo: That’s gratifying to me as a writer because you want it to be fresh, as we used to say, "Funky, funky fresh with the funky style."

Q: Was it fun to write about this "funky" time?

Perdomo: I was up at 11, 12 at night working on [this collection.] There’s music playing in the background from that era. Next thing I know it’s 4 or 5 in the morning. I’m dancing and revising. So, yeah, in that moment, the process was extremely fun because I could see it. I could see it blossoming. I feel like I was far enough removed from say, the night that Dre died, that I could write about it. I had the proper distance, physically in New Hampshire, and then temporally, because it was 20-something-odd years ago.

Q: You dedicated the book to your son. Why?

Perdomo: I think because it was at his age where I started wondering about what it means to belong. What are the masks we put on to be accepted at his age, 16? How does one define one’s masculinity? There are some things I might not be able to relay in the father-son dynamic that I’ll be able to relay as a poet to a reader, whereby if you’re looking for some sort of truth about my life, some of it is in there. Yeah, this is what your dad experienced. You should know that about me. So, when I’m giving you feedback, or I’m giving you advice, or suggesting something, it comes from an informed place, one who has been confronted with tragedy and love and joy and coming of age and confusion and conflict.

Q: Can you tell me about that time, as you write, "This is before the world went 2.0."

Perdomo: There were no cellphones then. Maybe the computer was just about to become part of our public consciousness. There was no sense of binary as a code, really. When it comes to identity, I don’t think it was as fluid. We were firmly entrenched in our young manhood, in our maleness and being Puerto Rican and being black in our culture. But this is a time where you had to wait for a phone call. Your network, as it were, your feeds, your narrative life was happening in front of the candy store. The way you heard stories was happening on the stoop.

Q: You started as an undergrad at Ithaca College, but didn’t stay long.

Perdomo: I was bored and my dream to be a published writer was humongous. My dream was just running wild. I was thirsty. I wanted to know. I wrote a couple of short plays. I wrote some poems for a lit mag and then an alternative newspaper, shot a short film, stuff like that. Even though I wasn’t going to class, I was still involved in my artistic life. Then I tried again at City College, where I met Raymond R. Patterson, who’s no longer with us. He changed my life.

Q: He was your teacher and mentor?

Perdomo: He taught me how to keep a notebook and he gave me a book that became my bar. A book called Cane, by Jean Toomer. It was written in 1923 during the Harlem Renaissance. It’s a hybrid book, basically. It was postmodern before they had a term for it. But the idea of hybridity, that a book can be more than just one thing, that has been my bar since.

Q: What was the most difficult poem to write?

Perdomo: The poem about Dre. That moment where we laughed initially when we saw him run down the street naked and high on angel dust. Then we laughed when he ran back. Then we heard that he had thrown himself off the rooftop of his six-story building, which was across from mine. We all grew up in the same complex. The idea that one minute you’re laughing, and the next it’s not so funny.

Q: What’s the genesis story of the entire collection?

Perdomo: The book started [in faculty housing], at 16 Tan Lane, in the living room at the Doctor’s House. My wife and I were watching a documentary about [rapper] Nas’ iconic hip-hop album Illmatic. It really triggered a current of memory that was filled with sadness, because a lot of the people that I knew who were casualties of the drug war came to mind. I missed my childhood friends, and I missed them for all of their joy and pathology. There were memories that were surfacing that I used as focal points for the larger arc of the book. I cried before I started the book. Then I hugged my wife and I ran to my study and I opened my notebook and the first stanza of "In the Face of What You Remember," which is the opening poem of the book, came out word for word as you read it.

Q: Where else did you draw inspiration?

Perdomo: One of my favorite movies is Cooley High. This book served as a love letter to Cooley High and hip-hop music, to the innovators like A Tribe Called Quest and Wu-Tang Clan. As hip-hop starts to innovate and offer testimony to what is actually going on in your neighborhood, on your block, in your country, and doing it with a jazz bass in the background ... that was interest- ing to me. Then there are poets that I read and reread. They all take different approaches to growing up young, male, black and Latinx in America. People like Reginald Dwayne Betts and David Tomas Martinez. There’s a whole category now of dysfunction that these poets are exploring.

Q: Would you put yourself in that genre?

Perdomo: Oh, yeah. At this point, I’m an OG in that world

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the summer 2019 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.