Getting at the truth

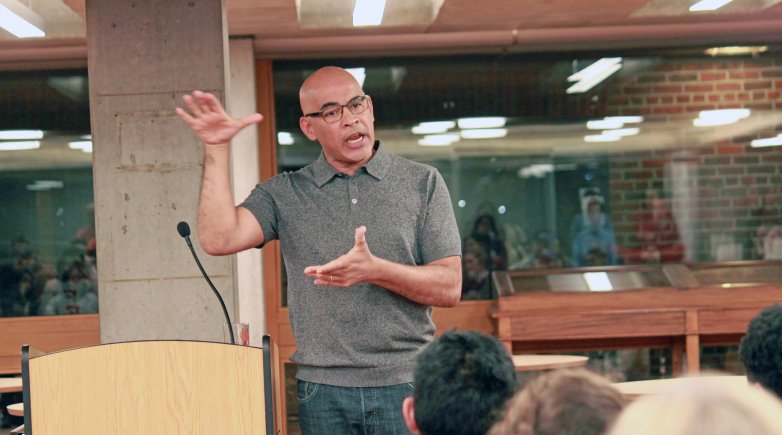

A conversation with professor and author Kim McLarin ’82.

Kim McLarin crafts stories that make the personal universal. With all of the vulnerability and honesty of a diarist, and the tenacity of a seasoned journalist, McLarin draws on her own experiences to explore race, rejection, parenthood and mental health in her latest work, “Womanish: A Grown Black Woman Speaks on Love and Life.”

In 13 frank essays, the 54-year-old author deftly dispels memes (“Who says online dating doesn’t work for black women?”), digs into cultural stereotypes (depression is some “white folks mess”) and invites readers along on her search for “a slice of the truth.”

“Womanish” is McLarin’s sixth book — including a memoir and the critically acclaimed novels “Taming It Down,” “Meeting of the Waters” and “Jump at the Sun.” She is a former staff writer for The New York Times, The Philadelphia Inquirer and the Associated Press, and regularly appears on the Emmy Award-winning television program “Basic Black.” We caught up with McLarin, now an associate professor of writing at Boston’s Emerson College, between classes to hear about “Womanish,” just as it hit bookstores this winter.

Q: Can you tell me about the book’s title, “Womanish”? What does that term mean?

McLarin: I grew up in the South, in Memphis, and the term “womanish” comes from a black folk expression. To be acting “womanish” means to be acting grown. Usually, it’s said by black mothers and grandmothers to a very young girl or their daughters. “Oh, you’re acting womanish,” which means you’re acting grown, you’re acting like you have more maturity and more thoughtfulness than you should at your age.

Q: Is it a positive word?

McLarin: It’s generally a kind of loving cautioning, a warning to stay in line. I’m using it in the sense of being fully in command of your womanhood. Audacious. Bold. Thoughtful. In the black community, there’s also an expression “grown ass.” Like, “You’re grown ass.” That’s a positive. That doesn’t just mean you’re old, that means you’re grown, that means you have embraced what it means to be an adult. In America, we celebrate perpetual adolescence.

Q: You are embracing your adulthood in this book.

McLarin: People want to be young, like youth is some-thing to be celebrated. I’m saying exactly the opposite, that we should celebrate true maturity and thoughtful-ness. Wisdom comes with age, if you live right. That’s what the book is about.

Q: You share really personal thoughts, like feelings of suicide. Is it difficult to write about that?

McLarin: The essays are personal, but they are not, strictly speaking, personal essays. So even though the me in these essays is me, it is not a totality of me. I have no fear about exposing myself because I know that what other people think they know is both true and untrue. My model for what makes a powerful essay is James Baldwin, one of the great voices of the 20th century. He wrote through his own experience, but he wrote something larger than that. So even though I’m writing about my experience with depression, I’m really asking bigger questions about what it means for a human being to be depressed. In my opinion, that’s what a good essay does. It starts with the personal, but it doesn’t end there.

Q: Do you think about what the people reading your work will think about you?

McLarin: No. I have something that is very useful for a writer, a kind of amnesia. It’s like I forget the fact that maybe someday other people are going to read this. I really just am so focused on trying to get at the truth of what I’m trying to say. I cannot tell the truth about the society in which I live, or the world in which I operate myself, if I also don’t tell the truth about me. I just can’t do that.

Q: What do these essays reveal about you that is true?

McLarin: That I’m human.

Q: There’s truth in all of the data you add to your essays as well.

McLarin: I worked as a journalist for 10 years and so I understand the persuasive power of statistics. I use them both to back up what I’m saying and also to solidify the point that this is not simply my interpretation. We understand the truth both through our own discernment and through whatever evidence we can marshal to support that discernment.

Q: If the job of the writer isn’t to answer the question, but to ask the question precisely, what questions are you asking in this book?

McLarin: I’m asking about depression, about mass incarceration, about true sisterhood between black women and white women. I’m asking how some children fall through the cracks and some children are saved. My children are both in college, whereas my sister’s child is in prison. We come from the same family. How does that happen? The luck of circumstance? I go to Exeter, my child goes to Harvard. What kind of society allows the luck of the draw to determine not only an individual’s fate, but generations’ and generations’ and generations’ fates?

Q: Coming to Exeter was a matter of luck? Can you tell me more about that?

McLarin: I was in junior high and an alum came to the school to talk about Exeter. I didn’t know where New Hampshire was, literally. But my mother, who was trying to protect us all from the ravages of being poor and being black in Memphis, Tennessee, saw this opportunity and said, you’re going. But it was strictly the luck of that alum coming to my school and me being present that day, and me taking the material home, and my mother having the wherewithal to recognize the opportunity. That’s just a series of luck, right?

Q: Would you say you are telling your story for a particular audience?

McLarin: I don’t think about that consciously while I’m writing. But I do make sure that I am not subconsciously doing that, if that makes sense. Because we are, as black writers in this country, the default, the dangerous default that we can often fall into, is to write for what Toni Morrison calls the white gaze.

Q: You mean writing specifically for white people?

McLarin: That’s the only thing that I check myself on. Am I writing to explain black people to white people? That is something I do not want to do.

Q: You write in many different formats — novels, essays, newspaper articles, radio shows.

McLarin: And I’m writing my first play, too! I think different kinds of writing engage different parts of the writerly brain, and you want to keep them all active. You use your imagination more in a novel and you use your analytical brain more in an essay. A play is a completely different thing because it’s all relying on dialogue. And you have to get the point across in an hour and a half. I usually have at least three projects going.

Q: Did you always want to be a writer?

McLarin: I knew when I was 10 or 12 that I wanted to be a writer. I loved books, I loved reading. It was one of the things that saved me during a challenging childhood.

Q: Was writing a strong suit of yours at Exeter?

McLarin: I had an English teacher, Mr. [Douglas] Rogers. He gave us an assignment to write a movie review. I don’t remember which movie I wrote about, but I remember the first line: You would think that people would have had enough of silly love movies. It was a play on the Paul McCartney song. He thought that was the cleverest thing and he told me at the end of that semester, “You are a writer.” He didn’t say you can write. He said, “You are a writer.” I will never forget that.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the spring 2019 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.