On high school campuses where many students may not align with a single religion, broadly scoped classes like Religion 597 offer another avenue for understanding what it means, at the deepest level, to be a person. “When I think about teaching religion to adolescents, I think about ferreting out, identifying, naming, discussing and comparing the personal and practical pieties, the value systems by which our students live, that which they hold most dear in their hearts, what’s really real for them, what really matters, what constitutes the center of meaning for them — all of which is encapsulated for me in the term ‘religion,’” Vorkink says.

An Episcopal priest and ardent world traveler, Vorkink has taught philosophy and religion at the Academy since 1972. He graduated from Yale and earned a divinity degree from Union Theological Seminary in New York. When he was 20, he spent a summer in Florida volunteering for Martin Luther King Jr. “Working closely with King showed me a different side of religion, namely, religion as praxis, or the practice of faith,” he says. He went on to study philosophy and religion at Harvard, leaving the doctoral program ABD (without writing his dissertation) to come to Exeter. Then in 2015, Vorkink wrote his thesis, entitled “Know Thyself: Why and How to Teach Religion and Philosophy to Secondary School Students,” and fulfilled the final requirement for his doctorate.

A key part of Vorkink’s unwritten lesson plan for the Silicon Valley course was to help students figure out how all of their individual choices in this technologically charged world pertain to their philosophical search to “know thyself.” “In a generation where our influences have expanded from our parents to millions of online users around the world, it has become harder for us to determine our own morals and make our own decisions,” Mia Kuromaru ’19 says. “This class helped me realize that every student should understand the importance of their own autonomy.”

Classmate Tina Wang ’19 noticed her habits changing throughout the term. “I’m much more aware of my own technology use now,” she says. “I often find myself pausing to think about the ethical dilemmas behind news stories I see. … This course pushed me, it taught me to question and challenge what we too often blindly accept.”

Vorkink was pleased to hear that what the students were learning in the classroom carried over into their everyday lives: “Probably the most encouraging comment any student made, and I heard it again and again in different contexts during this course was, ‘You know, I never thought about that.’ That was encouraging in terms of why the course was valuable to offer. … It made them think.”

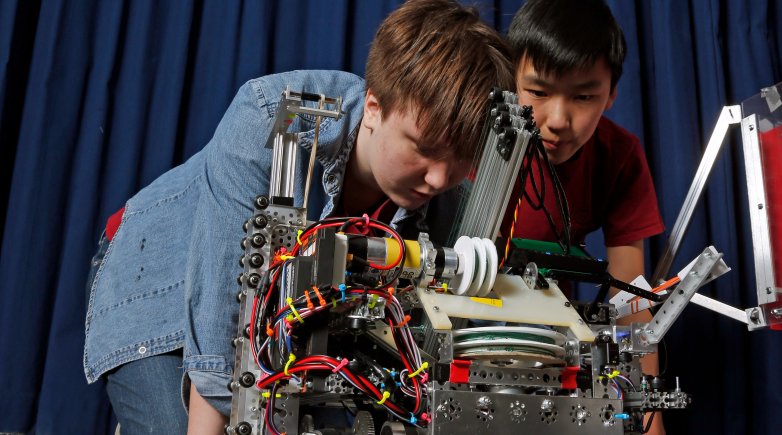

In a final act of reflection inspired by Jill Lepore’s New Yorker article “What 2018 Looked Like Fifty Years Ago,” Vorkink asked the students to imagine the technologies of 2069. Some prophesized a data-driven society completely devoid of privacy, while others saw the end of livestock farming in favor of cellular cloning of lab-grown meats. Many noted an increased reliance on robots to perform low-level jobs and the replacement of traditional “screens” with holograms. Each futuristic prediction was placed in the Academy Library vault as a time capsule, waiting to be opened during the classmates’ 50th reunion.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the summer 2019 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.