Beyond the table

Exeter students feed their hunger for discovery with passion projects outside the classroom.

Team VERTEX earned a spot at the robotics world championships in its first year of competition.

Not every inspiration occurs at the table.

Harkness works up an appetite for ideas and possibilities, for figuring out how things work and why things happen. That hunger for understanding continues to grow beyond the classroom door. Like a flame given oxygen, Harkness and its lessons spread.

Whether it’s inventors flocking to Design Lab during open hours or a blossoming poet filling her free blocks with verse, Exeter students are constantly exploring. Many of their biggest discoveries and brightest ideas are of their own making. Our fledgling robotics team tried-and-erred its way straight to the world championships. The collapse of a family beehive inspired a trio of seniors to study causes and seek solutions. Two members of the class of 2019 took advantage of the senior independent study program to pursue their arts in self-designed projects.

They represent a culture of invention and ingenuity at Exeter. Here are their stories.

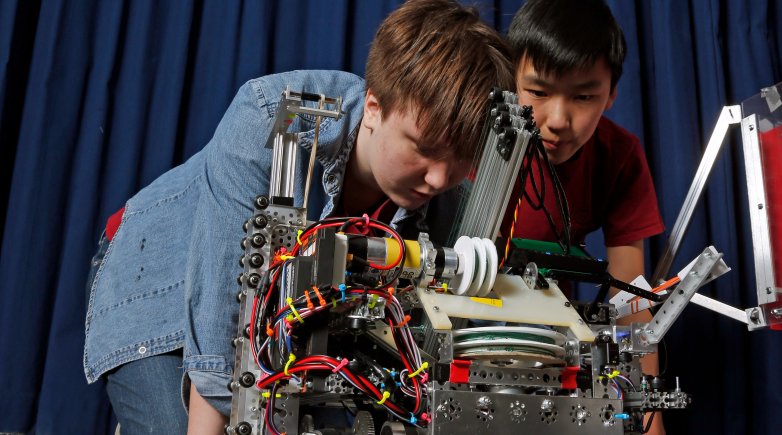

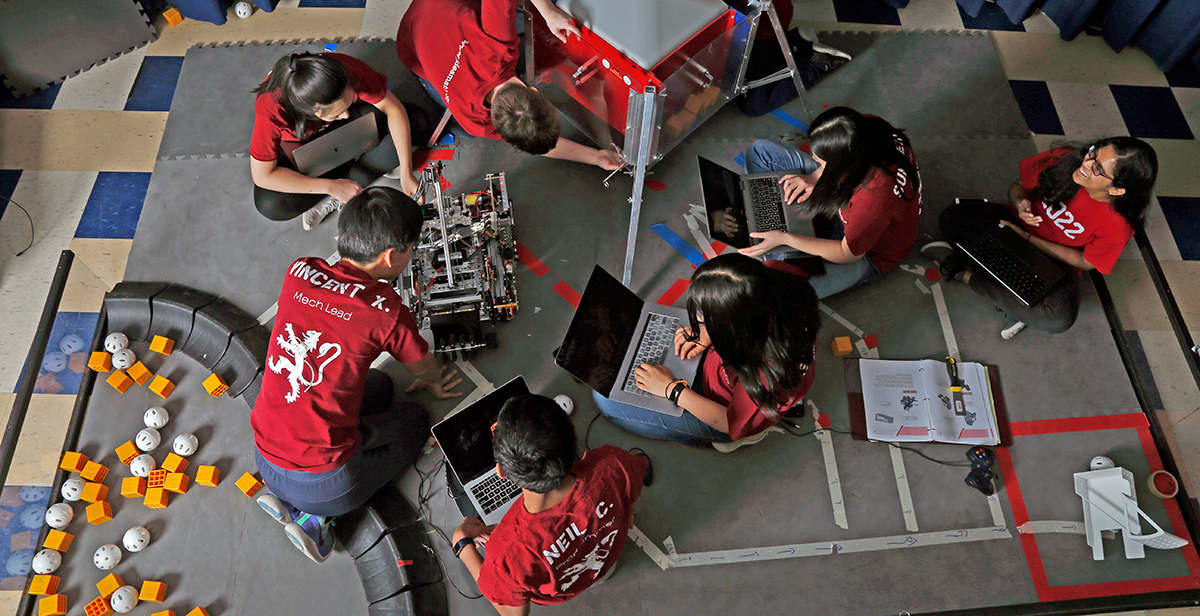

Rookie robot team has all the right stuff

By Nicole Pellaton

“They are VERTEX!” shouts the ref in a red Hawaiian shirt as he announces this match of Rover Ruckus, the regional FIRST Tech Challenge event held in February. He points to three Exeter students wearing protective goggles, nervous smiles, and red T-shirts emblazoned with VERTEX and the lion rampant: Vincent Xiao ’22 and Joy Liu ’20 (robot drivers) and Neil Chowdhury ’22 (match coach). Whoops from the crowd of thousands resound through Southern New Hampshire University’s athletic complex as VERTEX’s partner for this match and their two opposing teams are introduced.

As the racing bugle sounds, the teams’ four robots, simulating lunar rovers, drop from their tethered parking spots on the red landing craft to start their three-minute navigation of the pitch. The rovers, with long metal extenders and heavy-duty wheels, are designed to pick up “minerals” (in reality, Wiffle balls and plastic cubes) and deposit them in designated spots. After 30 seconds of entirely autonomous driving, buzzers blare and the driver-led portion of the match begins.

Clutching an Xbox controller wired to an Android phone that communicates with a second Android on the rover, Xiao gives robot 15534 a burst of speed. Its intake pulls in two balls, maneuvers one into the robot’s carrying cabin and releases the second back to the “crater.” 15534 swiftly backs up 4 inches, extends a long ladderlike arm above the landing craft and tilts the ball onto the craft’s roof. It bounces off. Again 15534 tries, this time with a cube. It goes in, but to the wrong spot. Two more attempts and success. “Nice job!” intones the ref.

The VERTEX alliance has won the round.