Independent spirits

Exonians making their mark in the craft alcohol world.

The picturesque Vermont city of Vergennes sits along the shore of Otter Creek, some seven miles upstream from where it empties into Lake Champlain. On a sunny day in late spring, a visitor can spend a pleasant while exploring the historic town center, with its refurbished Victorian-era opera house, nationally recognized ice cream shop and small but verdant City Park, among other attractions. Take a short drive down Main Street and across the creek and you come to a modest three-story building painted white. You’ve arrived — ideally thirsty — at the headquarters of Lost Lantern Whiskey, a leader among the growing number of independent bottlers of whiskey in the United States.

Started in 2020 by Vermont native Nora Ganley-Roper ’04 and her husband, Adam Polonski, Lost Lantern picks up on the Scottish tradition of independent bottling and reinterprets it in a distinctly American style. The company buys barrels of whiskey from different distilleries to resell under its own label, either as single-cask offerings or as blends.

“We want to bring this model to the U.S. in a really definitive way,” Ganley-Roper says while standing at the warm blond wood bar in the tasting room at the front of Lost Lantern; the production facility is at the back. Behind the bar, bottles filled with liquor in hues ranging from light maple syrup to deep amber reflect the sunlight. “There are other people starting to do it,” she adds, “but we want to be on the forefront of defining what the independent bottling tradition looks like here.”

Ganley-Roper grew up just 13 miles from Vergennes, in Middlebury. She came to Exeter as a new lower, fulfilling what had become something of a family tradition. Her mother, Barbara Ganley ’74, was one of the first four-year female students to graduate from Exeter; her maternal grandfather, Al Ganley, taught history at the Academy from 1964 to 1986. At Exeter, Ganley-Roper played violin in the orchestra and studied dance with longtime instructor Linda Luca. She also took every physics class offered. “In my very advanced physics classes, I was average, but then you realize later, once you leave, that average for Exeter is actually exceptional,” Ganley-Roper says.

Ganley-Roper grew up just 13 miles from Vergennes, in Middlebury. She came to Exeter as a new lower, fulfilling what had become something of a family tradition. Her mother, Barbara Ganley ’74, was one of the first four-year female students to graduate from Exeter; her maternal grandfather, Al Ganley, taught history at the Academy from 1964 to 1986. At Exeter, Ganley-Roper played violin in the orchestra and studied dance with longtime instructor Linda Luca. She also took every physics class offered. “In my very advanced physics classes, I was average, but then you realize later, once you leave, that average for Exeter is actually exceptional,” Ganley-Roper says.

After graduating from Barnard, she worked in finance for several years before parlaying her love of wine into a job at the premier New York City retailer Astor Wines & Spirits, where she rose to become a sales manager. Later, she honed her business acumen working at two start-ups in New York City. “I love building,” she says. “I love the process of creating processes and efficiencies, hiring people and all of that.” In 2018, Ganley-Roper and Polonski, a journalist and senior whiskey specialist at Whisky Advocate magazine, packed their belongings into storage and embarked on an eight-month road trip around the country. They visited more than 100 distilleries in a bid to explore the full landscape of American whiskey before founding their brand.

A key to the independent bottling tradition is transparency: The name and location of each distillery is listed on every bottle. Though good whiskey — particularly bourbon, a uniquely American spirit — has traditionally been associated with Kentucky and Tennessee, today roughly 2,600 U.S. whiskey distilleries stretch coast to coast, including Virginia, Colorado and California. Lost Lantern’s mission is to shine a light on the ones they believe are deserving of wider notice. The company works with more than 30 distilleries from about 20 states and is always looking for what’s new and noteworthy. “Good whiskey is just the baseline of what we do,” Ganley-Roper says. “We also want to be able to talk about the people that make the whiskey, the climate where it’s made, the processes they use that might be unique to what they’re doing.”

Among Exonians, Ganley-Roper is not alone in making her name as an entrepreneur in the nation’s growing craft alcoholic beverage industry. Whiskey in particular is enjoying a surge in popularity, with sales of American whiskey reaching $5.3 billion in 2023, according to the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States.

These are also boom times for smaller makers of wine, beer and other craft spirits. In such a crowded field, the most compelling entrepreneurs are those who focus on creating high-quality products that reflect who they are and what they value. They also succeed in blending an independent spirit with a deep connection to a community, and in creating — and articulating — strong visions and authentic stories behind their brands.

For Fritz Hatton ’72, the story behind his family-owned wine label, Arietta, combines his lifelong love of classical music with his pursuit of the heightened sensory experience and fellowship that sharing a great wine can bring. The brand’s name comes from the Arietta movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Opus 111. “It starts with a very serene arietta, or little song, which is followed by four variations of increasing layering and complexity,” Hatton explains. “Finally, the last variation takes the arietta heavenward. … It’s almost nirvana, in the Tibetan sense of a place of expanded consciousness and enlightened pleasure.”

At Exeter, Hatton played the piano and the French horn; among his fondest memories are performing with the New Hampshire Symphony in front of his fellow students in Assembly Hall and conducting the Richard Rodgers musical The Boy Friend in one of the school’s first coed drama productions. While in college, Hatton got a summer job helping a family friend open a wine and cheese shop in his hometown, Grand Haven, Michigan. He experienced a “wine epiphany” one humid night that summer, sitting on a porch overlooking Spring Lake and drinking a 1966 Corton Clos du Roi.

“It’s that moment of great discovery, which is not just the sense of the wine itself, but the sense of the socialization that it provides of bringing you together with people,” Hatton says. “Over the years, of course, one seeks to re-create that experience throughout life.”

In 1980, Hatton made the jump from wine retail to working at Christie’s, where he helped to establish the U.S. branch of its commercial wine auction program. As he rose in the management ranks, he also trained and worked as an auctioneer, eventually focusing exclusively on wine. By the late 1990s, he was one of the country’s premier wine auctioneers for both Christie’s and Zachys.

In 1980, Hatton made the jump from wine retail to working at Christie’s, where he helped to establish the U.S. branch of its commercial wine auction program. As he rose in the management ranks, he also trained and worked as an auctioneer, eventually focusing exclusively on wine. By the late 1990s, he was one of the country’s premier wine auctioneers for both Christie’s and Zachys.

Through his friendship with John Kongsgaard, a longtime Napa winemaker and co-director of the Napa Valley Chamber Music series, Hatton got an opportunity he couldn’t pass up: the chance to create and bottle wine from a block of Cabernet Franc grapes on the Hudson Ranch, situated in the rolling hills and cooler climate of Napa’s Carneros District. Since that first vintage was bottled in 1996, Arietta has become known for producing Bordeaux-inspired wines in the heart of one of California’s most prestigious winemaking regions.

“I grew up drinking mostly French wine for the first 20 years of my legal drinking … so my palate is tuned to European examples,” Hatton says. “We try to make the wines a little bit brighter, more food friendly, not too massive, and that’s our style.”

Hatton and his partner, Caren, purchase fruit from the finest vineyard blocks in Napa to make their Arietta wines. They have remained what Hatton calls “asset light” by not buying their own vineyards. “We’ve kept production to 3,000 cases, so it’s small and very personal,” he says. “We make wines to our taste, and we just have to find enough people who agree with our taste to buy the wine that we can’t drink.”

They’re in good company: Of the more than 11,000 wineries in the United States, 81% produce less than 5,000 cases annually, according to the nonprofit Craft Wine Association. This small scale has allowed Arietta to find its niche, especially thanks to recent legislation meant to benefit smaller craft makers and businesses.

They’re in good company: Of the more than 11,000 wineries in the United States, 81% produce less than 5,000 cases annually, according to the nonprofit Craft Wine Association. This small scale has allowed Arietta to find its niche, especially thanks to recent legislation meant to benefit smaller craft makers and businesses.

“It’s not easy,” Hatton acknowledges. “Family brands are largely disappearing in Napa because the costs are so high and the channels of distribution are shrinking. We’ve really been saved by the gradual changes in the laws of permitting direct-to-consumer sales in most of the states.”

In addition to its flagship red blend, H Block, Arietta’s portfolio has four other red wines — Merlot Hudson Vineyards, Cabernet Sauvignon, Quartet and Variation One — and one white, On the White Keys. The names, as well as the labels, reflect Hatton’s twin passions and help tell the authentic story behind the brand.

“If you know wine, you’ll pay up to a certain amount,” Hatton says. “Above that, it’s all about the romance, the story, the people and the experience you had enjoying that bottle.”

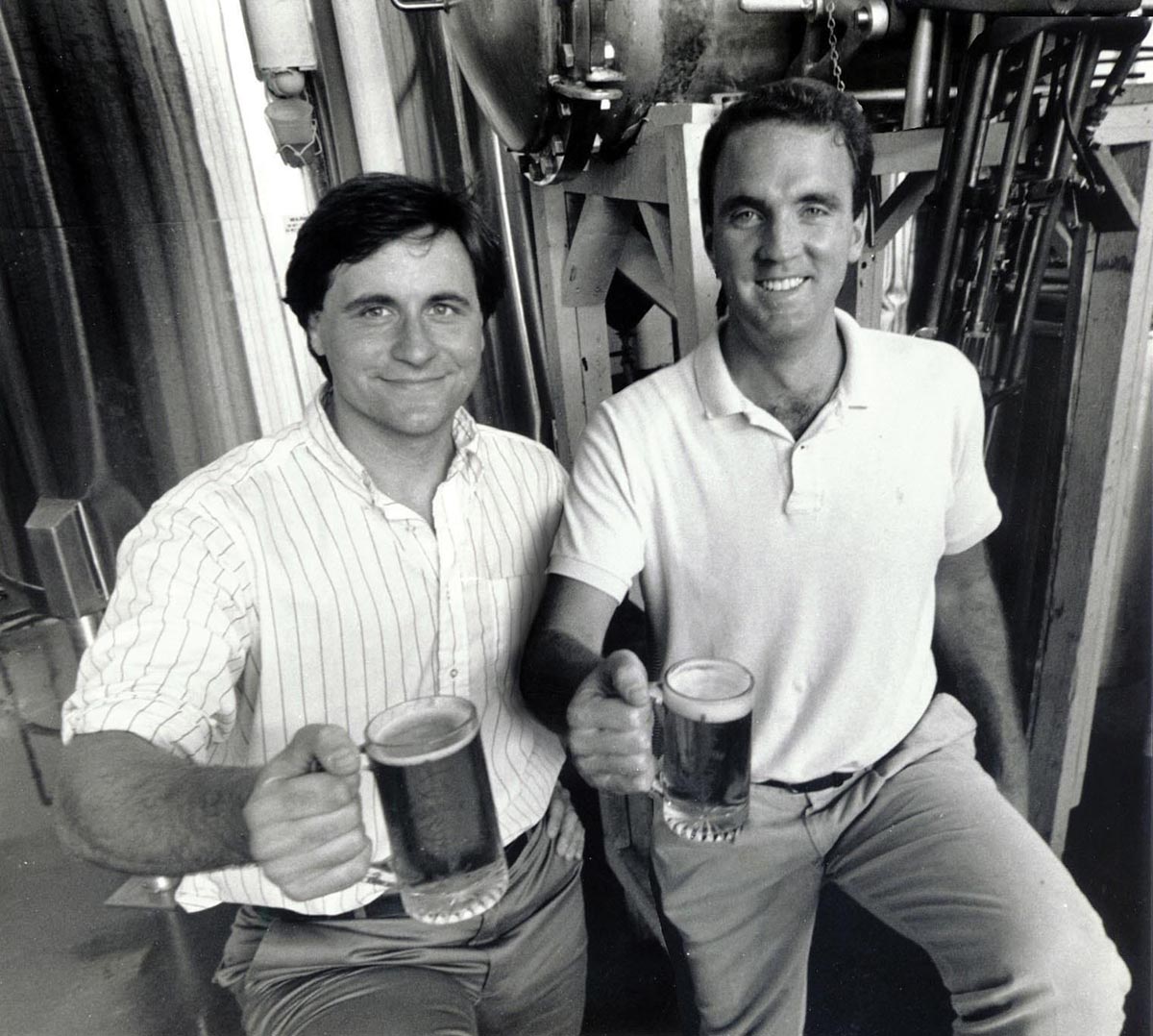

Rich Doyle ’78 knows the effect that authenticity — and the willingness to take risks — can have in starting a successful brand. In 1986, he co-founded Harpoon Brewery in Boston with two friends from college and business school at Harvard. It was inspired by the drinking spots they had visited during summer travels in Europe.

“Communities really feel pride in and rally around their local breweries there,” Doyle says. “I got the idea of trying to start a brewery that would mean something to the local community, that people would come and visit and be part of.”

Although craft brewing is now a huge industry in the United States, Doyle had hit on something relatively new at the time, especially in New England: Harpoon received Brewing Permit #001 in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. After producing its original Harpoon Ale in 1987, the brewery was soon introducing innovations such as the Winter Warmer, spiced with cinnamon and nutmeg, and the region’s first India Pale Ale, or IPA, which is now a staple of the craft beer industry.

Harpoon’s first Octoberfest in 1990 drew some 2,000 people to their brewery. Since then, the crowds have only grown, displaying the community spirit Doyle envisioned. “At our beer hall in Boston, we used to get 2,100 people on Saturdays, and there was a line to get in,” Doyle recalls. “It became more than I ever thought it would, and it was a great experience.”

Doyle stepped down as Harpoon’s CEO in 2014 as the company, at the time the 12th-largest craft brewer in the United States, transferred to employee ownership. After more than 28 years, he was ready for a new adventure. “I did 25 Octoberfests, and we did five events a year,” Doyle says. “I just thought, is the 39th going to mean that much to me? When you ask yourself questions like that, it’s time to go.”

His next venture, Enjoy Beer, aimed to partner with local craft brewing brands (like Abita, based in New Orleans) to consolidate costs and nurture their growth. The craft beer business had exploded: The Brewers Association estimates that as of 2023, 9,761 craft breweries were operating in the United States, representing about 24% of the U.S. beer market. With the knowledge gained from building a small regional brand like Harpoon into a national contender, Doyle knew he could help shepherd other independent brands through the growth process.

“There were all these small breweries popping up, and the big [beer brands] were starting to compete more heavily in the craft area,” Doyle recalls. “The idea was if you had a confederation of regional breweries, they could better defend themselves and prosper.”

Doyle worked on Enjoy Beer for a couple of years, but it ultimately proved difficult to build momentum. “The pricing got so bid up, we couldn’t conglomerate” other brands, he says. He’s now an investor in six companies, including Hero95, a beer company, and No Sleep Beverage, a holding company in the spirits and wine industry, in which he is also active. In addition, he teaches at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand, where he spends a month or two in the winter as an Entrepreneur in Residence.

Doyle’s advice to the brands he’s involved with now reflects his years of experience in an ever-expanding, ever-changing industry. “One thing that invariably comes up is focus,” he says. “Don’t be mile wide, inch deep. Don’t go everywhere and not be significant.”

He credits Exeter for instilling the internal clock that allows him to continue to be as effective as he was in founding and running businesses. A four-year senior and varsity athlete and captain in soccer, basketball and lacrosse, he also learned a lot about teamwork, collaboration and competition. “What I always said to people in the beer business — we had a lot of athletes who worked at our place — is that it’s very much like a sport, except there’s no clock,” Doyle recalls. “Game’s on all the time.”

Back in Vergennes, Nora Ganley-Roper is behind the bar guiding a novice through an Intro to Whiskey Flight that showcases four types of single-cask whiskey: a Kentucky straight bourbon, a California straight rye and two types of single malt.

“The idea is that if someone walks in here and says, ‘I don’t know anything about whiskey,’ then they can walk out and be like, ‘I really like bourbon,’” Ganley-Roper says. “There are rarely opportunities to taste different styles of whiskey that are very classic next to each other.”

As the flight progresses from the classic rich flavor of the bourbon through the bracing tang of rye and on to the single malts, Ganley-Roper offers a dropper with some water to adjust the whiskey to taste. McCarthy’s Oregon Single Malt lingers the longest, with its distinctive smoky flavor from the peat used to malt the barley. By way of contrast, a blend of single malt whiskies from Whiskey Del Bac in Arizona and Santa Fe Spirits in New Mexico substitutes mesquite wood for peat. The result, called Flame, was named the best American blended malt at the 2024 World Whiskies Awards.

Ganley-Roper and Polonski opened the first bottle of Lost Lantern whiskey at their pandemic-delayed wedding in 2020, a small ceremony in the backyard of her parents’ house in Weybridge, Vermont. Since then, as the company has grown, they’ve taken their production facilities and bottling in-house and work with retailers that can ship to customers’ doors in 40 states. At the tasting room, whiskey aficionados and newbies alike can choose from some 50 varieties.

After capturing numerous awards for individual whiskies, Lost Lantern won its biggest accolade in 2023, when it was named Independent Bottler of the Year at the global Icons of Whisky Awards, given by Whisky Magazine. Ganley-Roper traveled to London to accept the award at a gala celebration, taking her place alongside leading whiskey makers from Scotland, England, France, Japan and other countries.

At that very British occasion — the dress code was “lounge suit” — Ganley-Roper stood out. “I’m excited to be one of the few women because I think there is a lot of opportunity to bring in women to drinking whiskey,” she says. “I take a lot of pride in trying to be visible, and just have it be more normal that a woman owns or runs a whiskey company.”

Beyond offering great taste, expertise and a passion for the product, any successful independent maker of whiskey, wine or beer must find an authentic way to connect with consumers and create a community. Near the end of the tasting, Ganley-Roper offers one simple reason she believes Lost Lantern has been able to attract attention in a crowded craft spirit market.

“People buy our whiskey because they trust us,” she says. “I think that deep understanding of the place and the people and the process has been so much a part of building that trust.”

Editor's Note: This article was originally published in the Summer 2024 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.