Knocking down the patriarchal system in favor of one in which everyone has a voice is not only more equitable — it’s better for our mental health.

That’s where writer and psychoanalyst Naomi Snider is coming from in Exeter’s next virtual discussion before next month's symposium, “From ‘Studying Her Absence’ to Finding Her Voice: 50 Years of Coeducation at Exeter.” Snider lectures publishes on the intersections of social injustice and psychological struggle with a particular focus on the tensions between patriarchy and democracy at both the personal and political levels. Her published works include the 2018 book, Why Does Patriarchy Persist?, co-authored with feminist developmental psychologist Carol Gilligan who, in 1982, published the groundbreaking In A Different Voice.

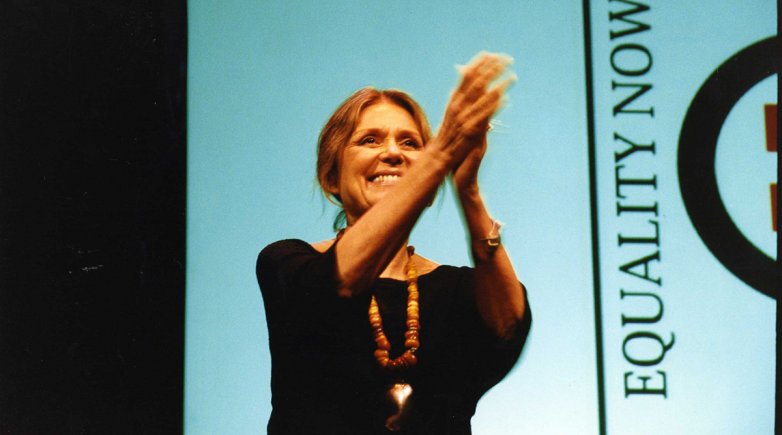

Snider will perform a reading and then join a conversation at 4 p.m. ET, Sunday, March 7. Her virtual visit is part of a series of discussions in the windup to an April symposium to be headlined by feminist trailblazer Gloria Steinem.

We chatted with Snider about her work and her visit:

Q: How did you originally become interested in the topic of your session?

A: I was a lawyer trying to forge a career in human rights, often feeling a sense of a frustration with how the system works, but without quite having a name to put to it. I was going to NYU to do a master’s in law, and a course called “Resisting Injustice” caught my eye: it was about literature and the law and psychology and finding your voice. It was co-taught by Carol Gilligan. As part of the curriculum, we read Carol’s 2002 book The Birth of Pleasure, and if I can pinpoint a moment where this question, “Why does patriarchy persist?” came alive to me was reading this book. It documents some of Carol’s discoveries in her research around children and developmental crises. We know that there’s this crisis in development that happens to boys and girls in different ways at different stages: in adolescence, at about the age of 12 girls are twice as likely as boys to suffer from mood disorders — depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation — and we know that boys around the age of 4 to 7 start having issues of acting out behaviors, more externalized mental health problems. This book captures Carol’s discovery that boys and girls were coming up against something in our culture that they were responding to that was causing these mental-health crises, and that something is patriarchy.