Tinker time

Design thinking class places experimentation and empathy at the fore.

In INT554 Design Thinking: Creative Workshop, weeks of brainstorming, planning, false starts, resets, feedback and perseverance culminate in one final work period. The mood in the Design Lab is unmistakable: It’s crunch time.

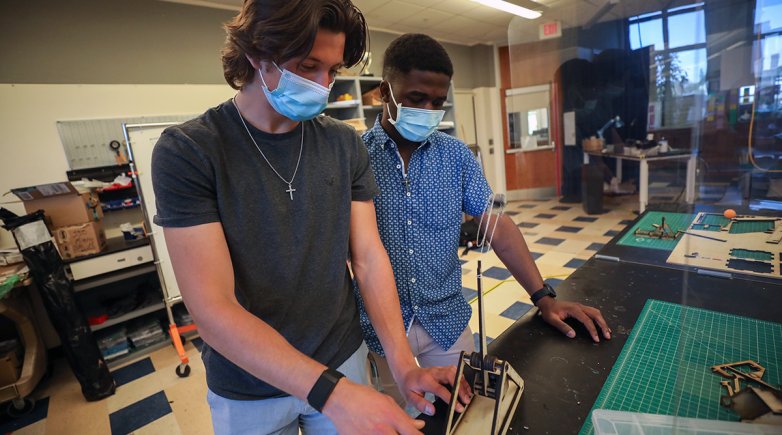

Students hover over high tables, collaborating like a team of surgeons, a quick trim of a jagged edge here, two, make it three, more dabs of glue there. The operation? Building toys for grade-schoolers.

In their second of three projects for spring term, 11 students working in three groups are developing concepts for a candy dispenser, a pinball machine and two small-object launchers — all inspired by Tinker Crates, a subscription service that provides young people interested in STEM with interactive projects that are as fun and rewarding to build as they are to play with.

“A lot of what students are doing when they’re designing is trying to choose among a variety of different ideas that are possible,” Instructor in Science David Gulick says. “It’s not necessarily that one’s right or wrong, but they’re trying to find their way through a variety of potential paths.”

The brainchild of Gulick and Instructor in History Meg Foley, the course traces its roots to the modern hub of innovation: Silicon Valley, California. In 2015, Trustee Jennifer Holleran ’86; P’11, who at the time was working for Mark Zuckerberg ’02 and his wife Priscilla Chan’s nonprofit Startup:Education, invited Exeter faculty including Gulick and Foley to tour a handful of Bay Area schools with curriculums based on the design thinking method. Key components of the problem-solving process include creating prototypes to be tested by a desired demographic and making refinements based on feedback.

Holleran is delighted to learn that the course, now in its fifth year, is flourishing as a space where students have the opportunity to add new ways of thinking to the Academy’s traditional pedagogy. “To teach the students to think about others and to listen in that way is very consistent with Harkness and comes through in design thinking, too,” Holleran says. “Harkness is so powerful, and we should never lose touch with that, but I think there’s an extension for the modern era that we’re in, which is, how do you actually then put things into action in the world?”

The wind up ...

Inside the Design Lab, James Manderlink ’21 tinkers with the tension on the arm of a table-top trebuchet. Spokesperson Nick Wang ’21 says the working title of their creation is “Build and Yeet.” “Yeet,” he explains, is “a fun way to say ‘huck.’”

The group is creating with fifth graders in mind and has already received feedback from their demographic. Teams sent early prototypes to children within the Exeter community along with videos outlining the steps for assembly. The kids replied with videos of their own, detailing their experience building and playing with the toys. If not for the pandemic, students would spend time with the children as they built and played with prototypes, taking notes on pain points and what looks promising.