In the presence of poets

Reflections on the impact of the Lamont Poetry series.

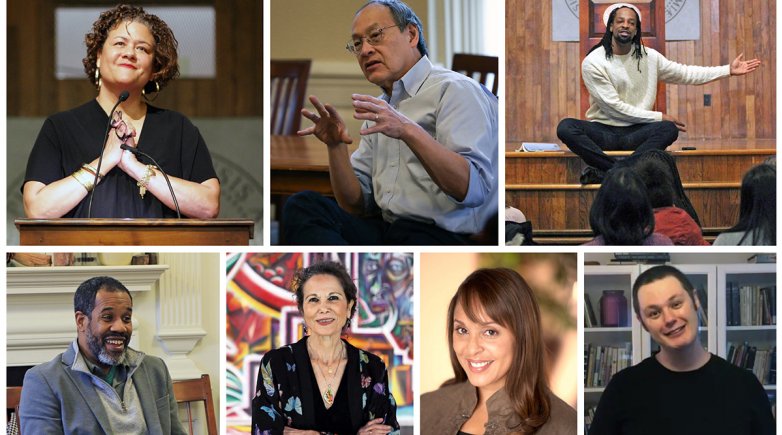

Recent Lamont Poets, clockwise from top left: Elizabeth Alexander, Arthur Sze, Jericho Brown, Ilya Kaminsky, Natasha Trethewey, Julia Alvarez, Gregory Pardlo. (Trethewey photo/Joel Benjamin, Alvarez photo/Brandon Cruz González/EL VOCERO DE PUERTO RICO)

It makes sense that the Academy’s twice-yearly Lamont Poetry Series readings fit so well within the frenetic groove of Exeter. Harkness, after all, is fundamentally an act of listening, attention and empathy — what is required to be truly present at a reading. In the crowded Assembly Hall on a weekday night, our community is unanimous: We all dedicate our undivided attention, and the poet dedicates theirs. We are most Exonian when we are listening.

Exonians, past and present, have so much to be grateful for in the programs that bring the foremost writers of our time to campus. Pore over the library’s archive of Lamont Poets and see what you find — Mark Doty, Allen Ginsberg, Philip Levine, Patricia Smith, Natasha Trethewey, Julia Alvarez, just to name a few — and one can see the legacy of literature carved into Exeter. Climb the concave steps to Assembly Hall and know that the weight of these names once imprinted on the marble you are ascending. Stand on the assembly stage and look out, underneath glaring stage lights, and think of the figures who have once stood on the same wooden floorboards as you now stand.

After a term of impassioned discussion over an author’s body of work, to see the writer — to know there is a real, breathing person behind their work who will answer your every question, comment and note — is an immense privilege. It is one thing to read "Beyond Katrina" in class. It is another to ask Natasha Trethewey a question about how the alternating prose/poetry structure informs the development of generational trauma in the Gulf Coast, to see her nodding in recognition as you speak, to see the slight pause of deep thought before she responds, to hear an answer you can’t wait to discuss in your next English class.

This live interaction is inseparable from the Exeter English experience. As a prep, good writing seems to exist on a completely other plane as to be achievable. But the opportunity to interact with master writers in almost casual exchanges has de-abstracted the deft composition of their work. I am nowhere close to approaching the agile expertise of these writers, but hearing their voices and lived experiences reminds me that they are real people, not ideas. I leave each reading with a mind full of possibility.

And this is not to say the Lamont Poet is only for writers. After a coffee discussion with Viet Thanh Nguyen in The Exeter Inn’s quiet alcove on the psychopathy of war and colonization, I have a refreshed, empathetic perspective to bring to my next history class. I can’t say that Arthur Sze’s explanation of parallel lines intersecting in the infinite as a metaphor for possibility has improved my calculus grade, but it has shown me the power of mathematical thought to model abstract concepts of humanities precisely. When I ask Ilya Kaminsky what he means when he says political and he chooses the original etymology — the Greek πολις, which simply refers to communal gatherings without the complex connotations of modern politics — I have a new dimension to bring to my Greek class discussion on Plato’s "Crito." Every crevice of Exeter’s interwoven intellectual web feels the impact of the writers we bring.

Inaugural Lamont Poet Jorge Luis Borges once said, “Art is fire plus algebra.” Our instructors teach us algebra throughout the term — the mechanics of a poet’s work. But then we bring the fire right to our campus and watch it glow in our Assembly Hall. We are so close to the fire it almost burns.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the winter 2021 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.