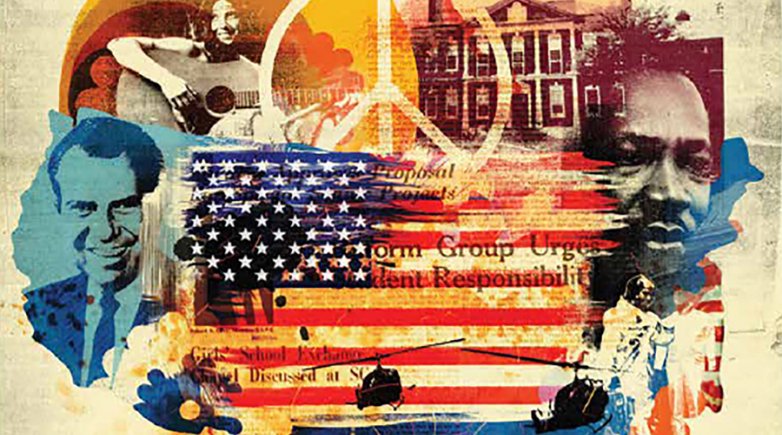

A random survey of The Exonian newspapers published from January 1968 to September 1968 yields the following headlines:

“PEA Succumbs to Feminism”

“Religion Department to Introduce Philosophy Course, Co-ed Classes”

“Mrs. Cunningham, Math Instructor, Named First Woman Faculty Member”

According to Heskel and Dyer, in After the Harkness Gift, the question of coeducation at Exeter first arose in the early 1950s — “… years before it became a focus of discussion at similar private academic institutions elsewhere.” Day’s immediate predecessor, the prescient and iconic William G. Saltonstall ’24, had been eager to transform Exeter into a “national high school,” and for some in his administration, admitting girls seemed like a logical progression. Detractors argued that females would pose too great a distraction, and the matter was eventually jettisoned, only to resurface again a decade later.

By the time most of the class of ’68 arrived at Exeter in the autumn of 1964, small numbers of girls had been attending Exeter’s summer session since 1961, and the trustee-appointed Academy Planning Committee, chaired by Science Instructor C. Arthur Compton, was recommending that the Academy add 250 girls to the school’s population. Coeducation was in the offing; it was just a matter of how and when. The fact that the idea was moving ever closer to becoming a reality, however, did little to allay the vexation of boys who, in 1968, found no girls on campus with whom to learn and socialize.

“The most challenging aspect of being a student at Exeter or other fancy prep schools during the mid- to late-’60s is that there were no females, period. None,” Scheer asserts. “This was a very strange way to live, especially given that most of us had come to Exeter from coeducational environments or had at least been to summer camps where girls were present. This kind of separation felt unnatural from the very first day for most of us.” Caplan agrees, adding that “students were all for coeducation, which probably had to do as much with instinct and longing as with how it would inevitably impact the school.”

Indeed, polls from the era indicate that a vast majority of students — and faculty — were in favor of admitting girls. Results of a survey published in the winter 1969 issue of the Bulletin show that 88 percent of students, 77 percent of faculty and 51 percent of alumni (with much stronger support from those who had graduated after World War II and the Korean War) supported coeducation.

Fortunately for Exeter, but perhaps not so much for students of the late 1960s, the coeducation matter reached its apex in the early days of 1970. After nearly two decades, numerous studies and a proposal, as late as the spring of 1968, to establish a boarding school for girls in close proximity to PEA, Exeter’s Trustees finally approved a plan to admit day student girls to the Academy in 1970 and boarding girls the following year.

While not a direct beneficiary of coeducation, Caplan was later able to observe its effects on the Exeter community. “In 1979-80, I was a White House Fellow, and from that point, every three to five years, I was invited back to Exeter as a guest of the History or English departments. In this way, I got to see the evolution of coeducation, which I believe made more of a difference in the ambience of the school and its level of happiness than anything else.”