Harkness’ experiences at St. Paul’s and at Yale shaped his thinking about education. Not a natural student, he struggled to maintain his grades and to adjust to the competitive environments at both institutions. When considering his gift to Exeter, he told Lewis Perry, “I want to see somebody try teaching—not by recitations in a formal recitation room where the teacher is on a platform raised above the pupils and there is a class of 20 or more boys who recite lessons. . . . I think the bright boys get along all right by that method, but I am thinking of a boy who isn’t a bright boy—not necessarily a dull boy, but diffident, and not being equal doesn’t speak up in class and admit his difficulties.”

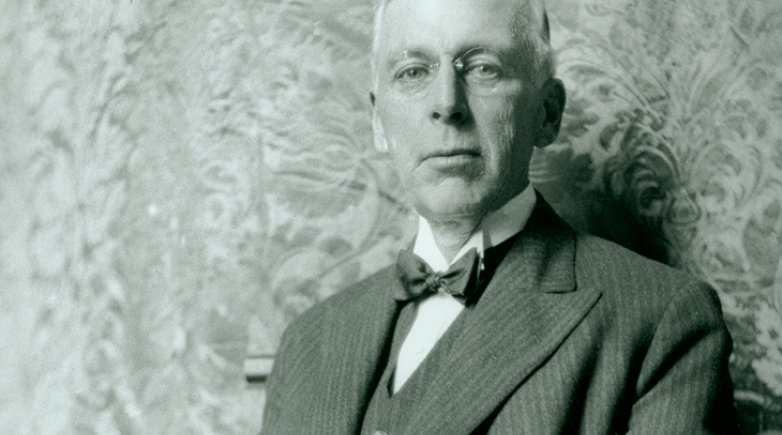

Although Harkness made gifts of up to a quarter-million dollars to Phillips Andover, Lawrenceville, St. Paul’s, Taft, Deerfield Academy and the Hill School, his gift to Phillips Exeter was his largest to a secondary school. It was also the gift that most clearly reflected his concept of a new approach to education and the one calculated by Harkness himself to have the greatest impact.

Exeter before Harkness

A century ago, in the years before the Harkness gift, lives of Exeter students were radically different from those of today. Classes were large (with 25 to 35 students in a section) and were taught recitation style, with the teacher lecturing to students who sat in rows. Teachers called boys by their last names, and when students wanted to get the teacher’s attention they did so not by raising their hands, but by snapping their fingers. In his 1923 history of Exeter, Lawrence M. Crosbie noted: “The casual visitor to a recitation in the Academy is always startled and sometimes shocked by the old Exeter custom of snapping the fingers. If the boy hesitates in his recitation, a fusillade of snaps from those who know or think that they know rings out. It is often disconcerting to a new boy, but he soon learns to stand his guns, no matter how fast the musketry rattles about him.” Students who did well in this environment were known as “sharks.”

Principal Harlan Page Amen, who led the Academy in the years before Lewis Perry took the helm, captured the prevailing spirit of Exeter in a reflection published in The Exeter Bulletin in 1906. “Too much intellectual and moral flabbiness is found in the students in our secondary schools,” Amen asserted. “The Academy’s demand for earnest study and manly conduct must, of course, be enforced by the designation of a penalty. The ultimate, if not immediate, fruit of idleness or misconduct is separation from the school.” Amen summarized his principles with the motto disce aut discede — learn or get out.

Also contributing to this stern atmosphere was the lack of a centralized residential or social life. Because there were not enough dormitory rooms on campus, most students lived in rooming houses in town. It was possible for students to attend classes and return to their rooming houses, having little interaction with the instructor or fellow students. For many students, the Exeter community consisted of the boarders with whom they shared their rooming houses.

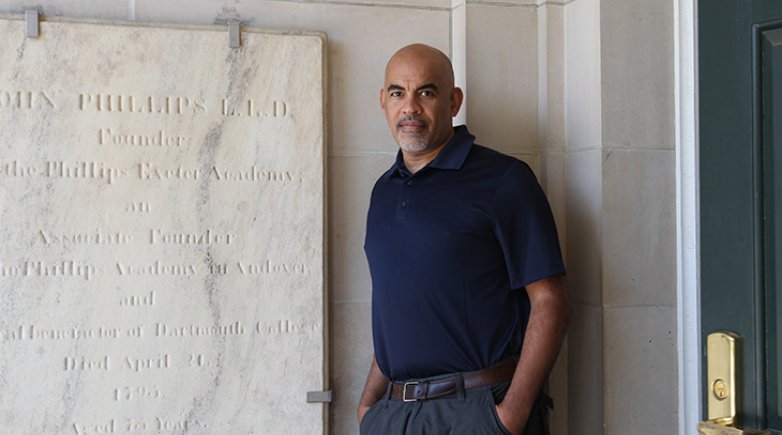

This was the world Lewis Perry entered when he became the eighth principal of Phillips Exeter in 1914, leaving behind a position on the faculty at Williams College as an instructor in English and elocution. Principal Amen had overseen the addition of a number of new buildings and the expansion of the campus, but the need for dormitory space remained a serious problem, and the Academy was in precarious shape financially. Two weeks after Perry’s election as principal, the Academy Building (the main classroom building on campus) burned to the ground. Perry immediately took on the task of rebuilding. Throughout the 1920s, he spearheaded fund-raising drives to reduce the Academy’s debt and make improvements to the physical plant.

A fateful friendship

When Phillips Andover received a substantial gift from a benefactor in the late 1920s, English instructor Frank Cushwa reportedly said to Lewis Perry, “We’re beaten. Exeter can never catch up.”

An article in The Atlantic Monthly published after the receipt of the Harkness gift reports Perry’s response: “ ‘Don’t be too sure,’ said Dr. Perry, in that calm, deliberate tone of his, bland and sanguine, which Young Men in a Hurry find so exasperating. ‘Don’t be too sure. Wait and see.’ ” The article goes on to comment: “Then came the 150th anniversary of Andover (1928) and Perry was invited to speak . . . What he said was that Exeter was little sister Cinderella, and that she was pleased to be asked to Andover’s grand party . . . unbeknownst to anybody, there was a catch in that speech . . . For little sister’s coach-and-four was waiting just around the corner of the next three years.”

Perry served as principal through June of 1946, a remarkable tenure of 32 years that spanned two world wars and the Depression. A beloved and revered leader, he shepherded Exeter through difficult times and oversaw a period of substantial expansion to the physical facilities and curriculum. Of all his achievements, however, none has been more enduring than his role in obtaining and implementing the Harkness gift, which shaped the physical dimensions of the Exeter campus as it is known today and instituted a teaching method that continues to influence educators.

Harkness might have been expected to make a major gift to St. Paul’s, his alma mater, but he chose Exeter in part because of his friendship with Perry. The men met at a wedding in St. Paul, MN, in 1902. Academy English instructor Richard F. Niebling, in an article for The Exeter Bulletin published in 1982, described theirs as “a lifelong friendship between two quite divergent personalities (perhaps the best after-dinner speaker in America, and a man who hardly ever spoke in public).” The Perrys often visited the Harknesses at their vacation homes in Connecticut and Charlestown, SC. Sharing a love for the theater, Perry and Harkness regularly met in New York to take in the latest productions on Broadway. Harkness recruited Perry to serve on the board of the Commonwealth Fund, further cementing their mutual respect.

Remembering Harkness after his death, Lewis Perry wrote: “I had never known in the early days that Ned Harkness was such a rich man. At this period I was an instructor at Williams, and whenever I came to New York Ned Harkness and I dined together and went to the theater. I always insisted that if Ned got the tickets, I paid for the dinner. Years after, out of the clear sky, Ned said: ‘You know, Lewis, that there is no man in the world I care for more than you. Do you want to know why? . . . Because you were such a damn fool that you did not know I had money.’ ”

Perry also recalled dining with Harkness the same night that the papers which created the Commonwealth Fund were signed. “He was very happy that night and welcomed the thought of what the Commonwealth Fund might accomplish,” Perry wrote, “but he was never overly optimistic about what his gifts would bring to pass. His was a wise and realistic attitude on the subject of giving. The road of a philanthropist is not always smooth, but Mr. Harkness always had in mind the good of humanity, and this consistent attitude made him the great humanitarian he was . . . Both [Edward and Mary Harkness] helped an infinite number of individuals, the type whom organizations do not assist, and they always helped in a quiet way unknown to any but the beneficiary.”

Harkness was motivated to make his major gift to Exeter because he trusted Perry’s judgment and ability to make good use of the money. “Exeter got the money,” Perry was later quoted as saying, “because Mr. Harkness knew we wouldn’t splurge with it.” Perhaps Harkness also realized that his close relationship with Perry could give him a degree of influence and oversight he might not have at another institution. However, it appears that in the end he chose Exeter because he believed, with its history and reputation, it was a school positioned to lead others. Harkness clearly saw his gift to Exeter as only the beginning. It was his hope that the method of teaching he helped introduce at the Academy would become a model for schools nationwide.

Change at the college level

In addressing the needs of secondary schools, Harkness was taking a logical next step, building on gifts he had earlier made to Harvard and Yale. Both independent secondary schools and colleges had seen steady growth in the early 1900s, without making many accommodations for the larger enrollments. Harkness wanted to address the problem of classes that were too big and based on a rote approach to learning and the problem of inadequate housing and a decentralized—or nonexistent—campus life, problems he saw as inextricably linked. He was particularly concerned about the segregation that occurred between the full-paying students and scholarship students, based on the housing they were able to afford off campus. A residential campus with housing for all would promote greater equity, encourage a closer relationship between teachers and students, and establish a cohesive social life allowing students of all backgrounds to interact on a regular basis.