Exeter returns to the 'front lines' of climate change

Eighth annual Climate Action Day raises awareness of challenges to the environment.

Students help to plant a variety of flowers and shrubs to attract bees, butterflies and other pollen-carrying species as part of Monday's Climate Action Day programming.

Relegated to Zoom for two successive springs, Exeter on Monday brought the action back to Climate Action Day.

Hundreds of PEA students, faculty and staff fanned out across campus and locations around the Seacoast to study challenges to our environment and, in some cases, literally dig into the problem. Now in its eighth year, Climate Action Day is intended to raise awareness of climate change, teach students about their natural world and reflect on environmentalism as an integral part of human existence. This year’s programming included projects such as planting pollinator gardens and pulling invasive weeds along with a keynote address from Daniel Schrag, the director of Harvard University’s Center for the Environment.

For 2020 and 2021, Climate Action Day was contained to the virtual space. The traditional and more robust program resumed this year as the Academy continues work on an ambitious climate action plan that will set the school on a path to zeroing out its carbon footprint and setting sustainability goals for generations of Exonians to come.

'Opportunities to lead'

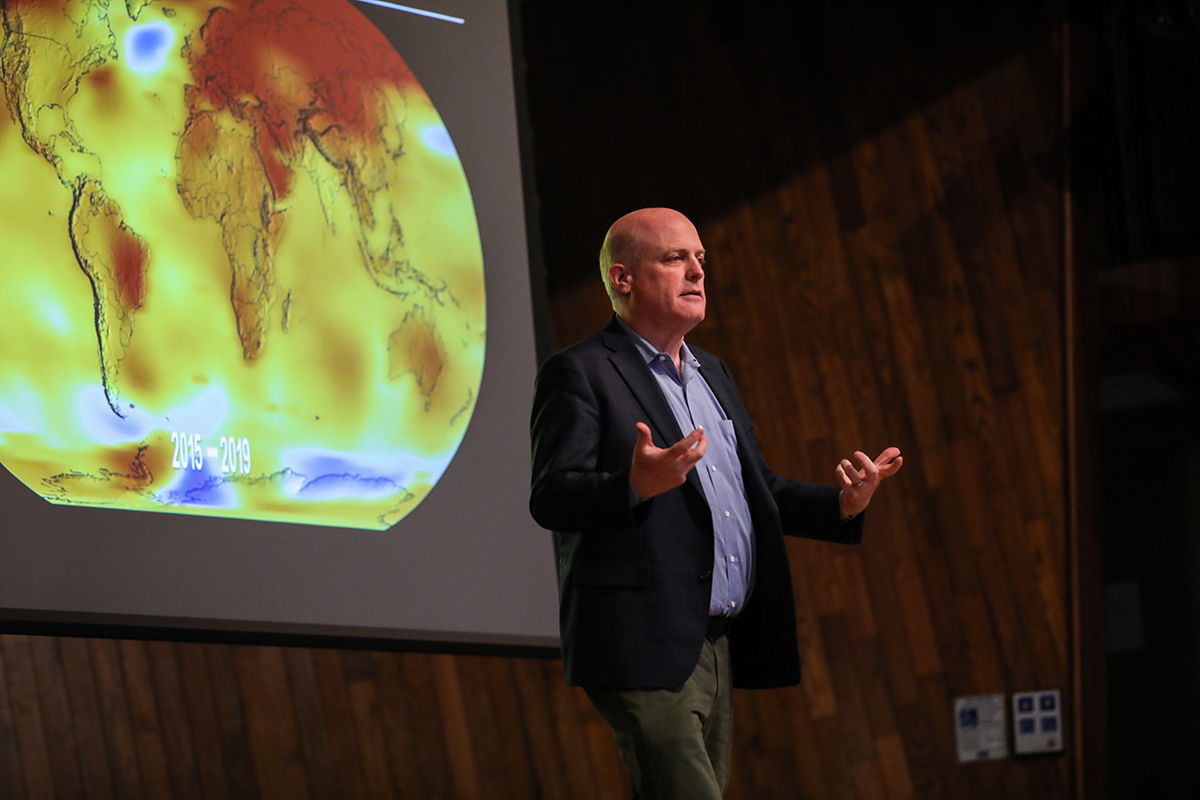

The day opened with Schrag's sobering assessment of Earth’s current and coming predicament — and of humankind’s inability to grasp the enormity of the problem.

The issue of climate change, he said, requires collective action and long-scale commitment, two things humans are not very good at.

Schrag also discussed climate injustice, something he is focused on exposing and helping to alleviate. “The issue is one of fundamental unfairness,” he said. “Most of the people affected by climate change did very little to contribute to the problem in the first place.”

He said confronting the problem of climate change requires global action, a difficult sales pitch to developing nations who are to date mostly not responsible for the carbon emissions warming the planet. “All of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa together are responsible for 1 percent of carbon dioxide emissions. Telling India, Asia or Africa they have to reduce their emissions seems a little bit capricious.”

Schrag doesn’t sugarcoat his message but he left his Exeter audience with some inspiration. “It’s really easy to feel small, powerless, throw up your hands and just see what happens,” he said. “But I think there are plenty of examples of people who have managed to inspire people to take action and change the way we think about this problem.

“There are opportunities to lead the world forward.”

Planting and plucking

After the keynote address, the Exeter community divided into small and larger groups for hands-on activities. On the south side of campus, a group of around 40 students gathered to plant trees, native shrubs and flowers behind the school’s tennis courts.

Bernadette Norton, a horticulturalist in the Facilities Management department, kicked things off by listing some of the plants that the students would be working with, including echinacea, milkweed, winterberries, bay berries and asters. Standing in a rectangular plot of straw-like grass dotted with dark green pots, she gave a brief tutorial on how to plant.

“This has got really good soil on the top part here, but the next layer will be crushed stone, and below that are bigger stones,” Norton explained. “So, when you dig the hole, you want to make sure it’s not too deep.”

After Norton’s introduction, the students got to work. “I think we have over 100 plants right now, so everybody’s expected to plant at least two,” said Armanee Stenor ’23, one of the leaders of the “Native Shrub and Pollinator Garden” project. Stenor and Ty Carlson ’22 organized the project as the service component of their Biology 470: Human Populations and Resource Consumption course.

“We’re planting flowers and a few shrubs as well, all focusing on different things that would attract pollinators,” Carlson added, referring to bees, butterflies and other pollen-carrying species that are vital to the survival of many plants and crops. “[We focused] on having a lot of flowering, a lot of different colors.”

Working alongside them in the garden was a group who signed up for a separate tree planting project, led by three students who also took Human Populations and Resource Consumption. “One of the best ways to solve climate change — at least that we can do on a small scale — is planting trees,” said Barron Fisher ’22, one of the project leaders. “We thought it’d be really fun to get out here for Climate Action Day and do a hands-on project.”

Nearby, another group of around 20 students focused on removing garlic mustard, an invasive species prevalent in the area, from along the fence lining the back of the athletic fields. As piles of the leafy greens mounted, project leader Montana Dickerson ’23 predicted that the day’s climate activism might produce an unexpected bonus. “After you pull it, you can actually use it for food,” Dickerson said, mentioning garlic mustard pesto as one potential recipe. “Hopefully we’ll be able to salvage some of this and upcycle it into something you can eat.”

Poetry: a growth industry

It can be hard to find poetry in a row of turned-over soil, but 120 members of the class of 2025 could draw the connection between the work they’re studying in the English classroom and the work they did Monday on Saltonstall Farm in neighboring Stratham.

The common text for ninth-graders this term is “Lace & Pyrite: Letters from Two Gardens,” a correspondence of poems between poets Aimee Nezhukumatathil and Ross Gay. The series of epistolary poems, exchanged in 2011 and published three years later, was written between Nezhukumatathil’s flower garden in New York state and Gay’s fruit and vegetable garden in Indiana.

On Monday, the ninth-graders’ muse was kale. Armed with scores of seedlings provided by their hosts, the students lined a long garden row and transplanted the kale, which — with the cooperation of Mother Nature — will be ready for harvest in 60-80 days. Compost was generously applied to the pipsqueak sprouts, with each prep digging their hands into a wheelbarrow filled with the rich mixture.

“What is compost exactly,” asked one wary new farmer.

“Organic material,” answered English Instructor Duncan Holcomb.

“Organic material as in …?” the inquiry continued.

“As in everything you need to create life,” Holcomb said.

After getting their hands dirty, the students heard from their hosts about crop lifecycle, pest and weed management and the fertilization their plantings require. Saltonstall Farm is owned and operated by Sophie Saltonstall ’07 and her husband, Kyle. Sophie Saltonstall — whose great uncle was the ninth principal at PEA — grew up on the farm; she is the third generation of her family to serve as steward of the property.

On the 'front lines'

Just six miles north of campus lies the Great Bay, a 6,000-acre tidal estuary and, as Kelle Loughlin of the Great Bay Discovery Center described, an asset in navigating the effects of climate change. Speaking to a group of 20 students along the rocky shore, Loughlin explained that as ocean levels rise, in-land ecosystems that can accommodate saltwater will become the “front lines” of defense against rapidly encroaching coastlines.

Monday, the students focused their attention on land, hunting for and removing invasive species on the discovery center’s campus. Loughlin presented a slideshow of the day’s most-wanted plants, including bittersweet and wild garlic. Loughlin discussed how another invasive species in the area, the multifloral rose, has put environmentalists in a predicament. The shrub has become a food source for the endangered New England cottontail.

Equipped with gloves, shovels and clippers, the students spread out in search of their targets. As students dug and clipped, garlic shoots were set aside to be sampled on top of baked potatoes provided by the center as a parting treat.