Icon Ginsburg's portrait the work of Constance Beaty '73

Alumna's likeness of late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg will hang in Supreme Court.

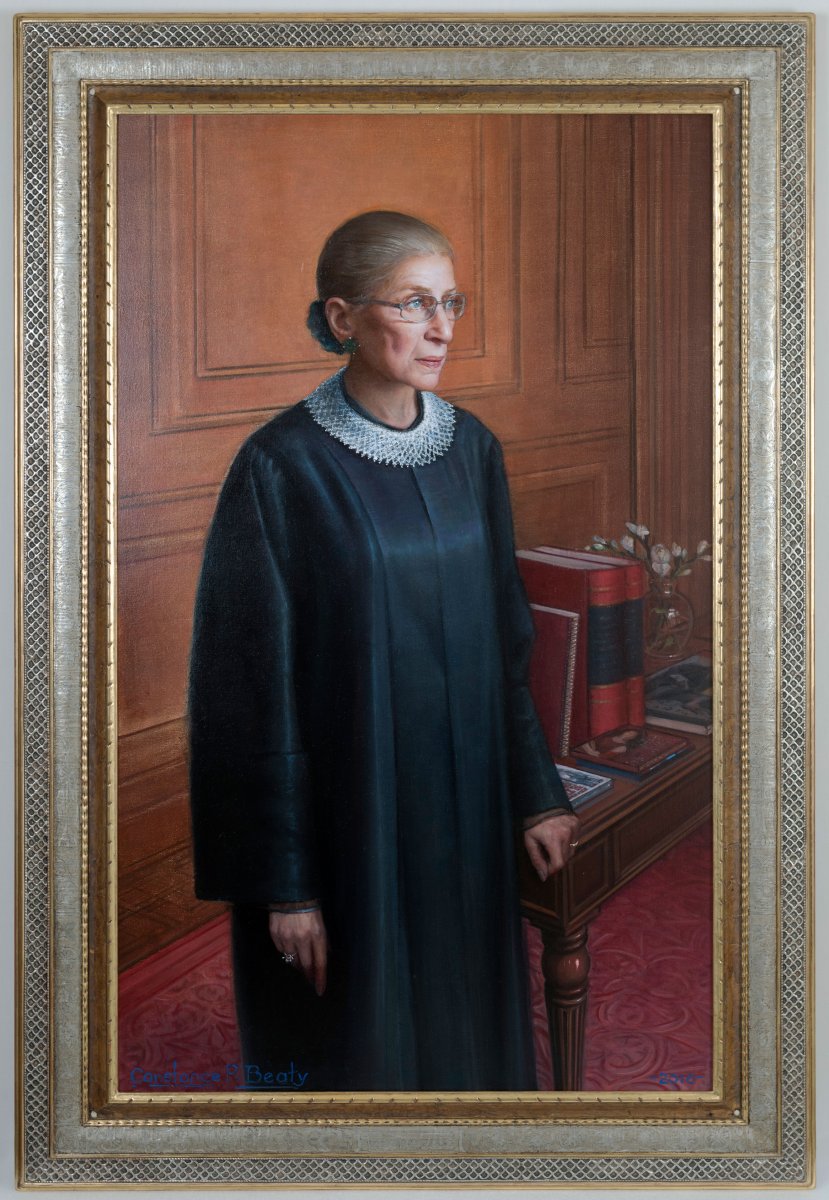

Kim Beaty's portrait of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is displayed in the Supreme Court's Great Hall as the justice's casket arrives for a brief ceremony Sept. 23, 2020. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

On Sept. 23, a brief ceremony of repose for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was held in the Supreme Court’s marbled Great Hall. Watching over the proceedings was a 2016 oil portrait of Justice Ginsburg painted by Constance “Kim” Beaty ’73 that is slated to be the official portrait of the justice and hang in the Court in perpetuity.

Beaty’s selection as official portraitist requires rewinding to the 1960s, when she and Jane Ginsburg, daughter of the future jurist, met as classmates at Manhattan’s Brearley School, where they were until Beaty left and enrolled as an Exeter upper. A few years after her mother was appointed to the Supreme Court, Jane reached out to invite Beaty to put her name in to paint a portrait of the justice for Columbia Law School, where she had taught. Justice Ginsburg liked that painting so much, she told Beaty her name would be at the top of the list for her official Supreme Court portrait.

“Justice Ginsburg was a person of her word,” says Beaty, adding, “I always thought it would not have been unlike the justice to have tried to choose a woman” for the job.

The process began in 2014, on a quintessentially humid D.C. summer day.

“I said, ‘Justice, I’d love to be able to get up higher than you. Would you mind terribly if I stand on your desk?’ And she looked a little startled and said, ‘Um, no. That would be fine.’” So, Ginsburg moved some files and Beaty removed her shoes and climbed up on the mahogany desk. In the patter she uses to keep her subjects —or, as she calls them, “victims” — engaged and awake, Beaty asked Ginsburg what case was most memorable to her, as either a success or a failure.

“She very quietly looked me in the eye and said, ‘Well of course, the ERA’,” referring to the Equal Rights Amendment, which was approved by Congress in 1972 but fell short of ratification by the states. “And I said, ‘Oh, of course. You don’t think it’ll come back again?’ And there was a terrible pause, and she looked at me again and said, ‘Not in my lifetime.’ Which is prescient and terrifying.”

Over the two years it took Beaty to complete the 30- by 40-inch painting, they would have many such conversations.

“She was obviously fiercely intelligent, but she had enormous thoughtfulness,” Beaty recalls. “She was extremely concise in her way of speaking. She would look at you for a minute, and then when she spoke, what she said came out in a fully formed paragraph of thought. She spoke very deliberately and quite slowly, and then she would stop — and if you weren’t careful, you would step on her next thought. You couldn’t just jump in there — she might not be done!”

The portrait is formal; Justice Ginsburg chose to wear her robes rather than street clothes. She also selected the location, and — with some prompting from Beaty — the iconography: a couple of Jane’s legal texts; a copy of Chef Supreme: Martin Ginsburg, a cookbook tribute to her late husband; and CDs produced by her son James are all visible in the painting, along with a bouquet of freesias, her favorite flower. A commissioned frame echoes many of the themes in the portrait, including her iconic lace collar.

The portrait is formal; Justice Ginsburg chose to wear her robes rather than street clothes. She also selected the location, and — with some prompting from Beaty — the iconography: a couple of Jane’s legal texts; a copy of Chef Supreme: Martin Ginsburg, a cookbook tribute to her late husband; and CDs produced by her son James are all visible in the painting, along with a bouquet of freesias, her favorite flower. A commissioned frame echoes many of the themes in the portrait, including her iconic lace collar.

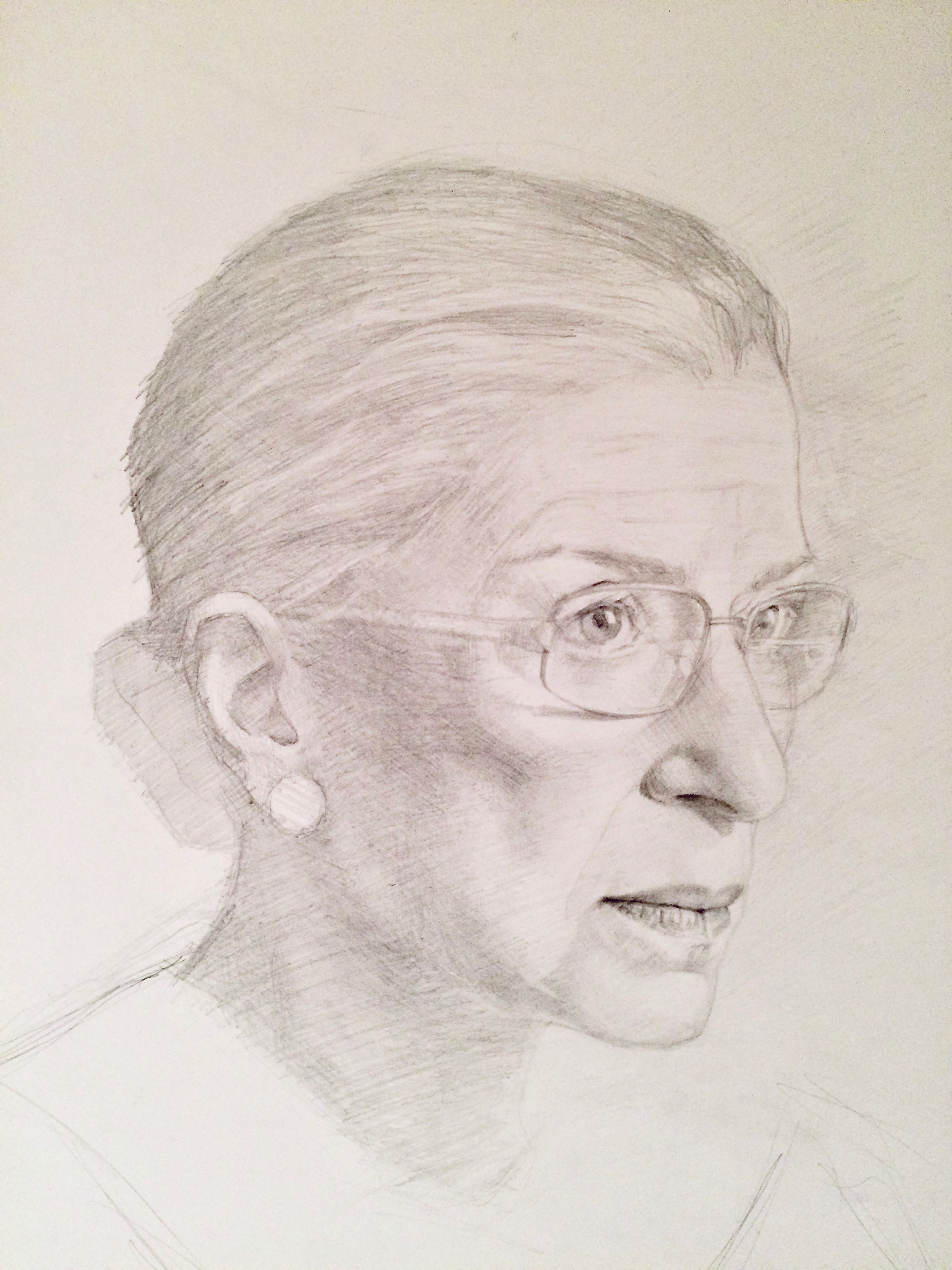

Ginsburg approved the final product, though Beaty was partial to another, a much less traditional extreme close-up of the justice’s head.

“She really had the most beautiful eyes of the most extraordinary color. Most people didn’t have the opportunity to see her up close,” says Beaty by way of explanation for her preference for that portrait, Large Oil Sketch: Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The justice eventually donated it to the Brooklyn Museum.

Beaty hadn’t planned on a career in portraiture. At Yale, she studied French literature and wrote a thesis on Molière. The granddaughter of composer Richard Rodgers and daughter of writer and composer Mary Rodgers, Beaty was perhaps destined to spend a decade on and off Broadway. Ultimately deciding her heart wasn’t in acting, she enrolled at the National Academy of Design School of Fine Art and studied under Ronald Sherr, future portraitist of Justice Anthony Kennedy and both presidents Bush.

Returning to school in her late 20s meant Beaty was focused.

“That was the advantage of being older: I thought if you’re going to put your eggs in the artist basket, you’d better learn to be good at this!” she says. “I did exactly what I was told, and pretty soon people started giving me money to do it. I never looked back.” But women who entered the portraiture business at that time found themselves up against a glass ceiling — without a solid resume, says Beaty, you  couldn’t get the best portraits, and vice versa. She quickly discovered that as C.P. Beaty, however, she could not only enter shows, the traditional starting point for an artist’s career, she’d win prizes, too.

couldn’t get the best portraits, and vice versa. She quickly discovered that as C.P. Beaty, however, she could not only enter shows, the traditional starting point for an artist’s career, she’d win prizes, too.

Today, Beaty, who has one adult daughter and lives in Vermont, chairs the board of the Dorset Theater Festival. She had been planning to expand her in-studio teaching until the pandemic hit, and is focusing instead on a series of portraits of young women.

“I think the young women coming up are really quite extraordinary. They’re this interesting marriage of feminism and femininity,” Beaty says, adding that she’s doing the series for fun, but may create a show with it in future. Among the three paintings she’s close to completing thus far: a portrait of Clara Spera, lawyer and granddaughter of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Exeter is celebrating 50 years of coeducation. See more coeducation news and learn about upcoming coeducation events.