I came back here to teach because I felt that the institution values what I value — openness, dialogue, genuine humanity, a belief in goodness — and I saw that there was a lot of change that could happen. I like to be an advocate for change. "

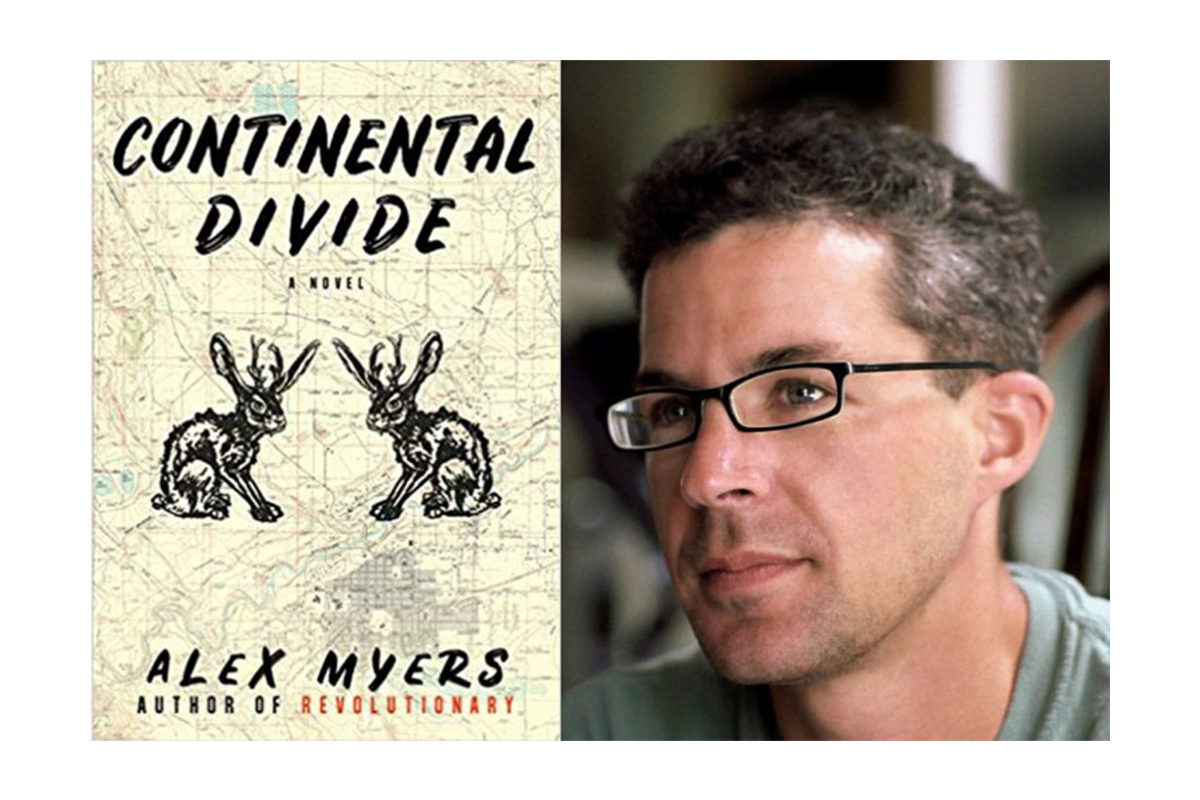

Alex Myers

Alex Myers fights for inclusivity, equality and plain old human goodness. Myers was Exeter’s first openly transgender student, attending as a girl for three years and returning for his senior year as a boy. Today, he shares his values by advocating for others, teaching English and writing fiction.

“Writing has helped me understand my gender and my identity in a way that I don’t think I would have been able to if I’d just talked about it,” Myers says. His debut novel, Revolutionary, mined the story of Deborah Sampson Gannett, America’s first female soldier, and was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award in transgender fiction.

His new novel, Continental Divide, published last fall, hits closer to home. Drawing on his own experience during a challenging summer in Wyoming, Myers introduces readers to Ron — formerly Veronica — a transgender teen. Ron ventures out West where he lands work at a dude ranch and finds himself battling bigotry from co-workers. It’s an experience that proves exhausting, overwhelming and life-threatening, but Ron, like Myers, perseveres. Myers’ well-crafted narrative contains immersive descriptions of Ron’s new world, from air filled with foreign scents (“I breathed in sage and the sharp resin of pine”) to detailed touches that evoke a canny immediacy, as when Ron finds himself in a group of Forest Service firefighters tucked into their sleeping bags “like rows and rows of string beans.” We caught up with Myers, now in his fifth year teaching at the Academy, in between dorm duties to chat about his life and body of work.

As a high school senior, what was it about Exeter that made you feel comfortable enough to be openly transgender?

People here, unlike in a lot of the rest of the world, listen. That’s one of the best things about Harkness: You have to listen for the system to work. I felt that I always had a voice. Even when people didn’t really want to listen to me, there were contexts in which they had to, and where, in turn, I had to listen to them. I had to learn to articulate myself, defend myself and be a good human. I came back here to teach because I felt that the institution values what I value — openness, dialogue, genuine humanity, a belief in goodness — and I saw that there was a lot of change that could happen. I like to be an advocate for change. That’s so intensely frustrating on a political level; it’s much easier in a community like Exeter.

How much of this new novel is based on your own life?

The skeleton of the story was based on my experience; the fictional flesh includes the characters and a lot of the minor incidents. I did head out West, I had gotten a job as a cook on a dude ranch in Wyoming. But after a couple of weeks I was fired. A friend of mine sent a postcard that mentioned that I was trans and the boss fired me on the spot. I did get a job with the Forest Service, but I did not come out to everyone there. I was very much in stealth mode and it both felt awesome — in terms of realizing that I could do that — and terrible and confining because I was continuously hiding and hounded by this secret, wondering what they would do to me if they found out.

Why did you choose that particular experience to turn into a novel?

It’s just one of those magnetic times in my life that I always come back to. …I loved that summer. It was such a beautiful place and so formative. It was so personally challenging for me to go there. It’s always been one of those times that thinking about it, even after all this time, can still bring me to the verge of tears. And I feel unbelievably lucky: it wasn’t but four months after I got back that Matthew Shepard was murdered. I just remember hearing about that, having that absolute stomach-drop moment of, “That could have been me.”

As a teacher, how do you share your experience with others?

I try not to pull my personal story into the classroom. It’s in the dorm that I talk most about my personal life. There, I’m a person rather than just a teacher and the kids are very curious. I also run an affinity group for transgender and nonbinary students, and that’s a great place to share.

How do you keep your writing and your teaching separate?

The great thing about Exeter is the student-centered learning. Whether I’m teaching preps how to craft a paragraph or working with seniors to improve their fiction, I always deflect the conversation back to them. If they say, “You’re the professional writer, how do you do this?” I’ll say, “I can tell you what I do, but I’m more interested in you telling me how you’re figuring this out.” It’s about making them do the work. I’m the mean teacher that way.

Were there faculty members whose support had a particular impact on you?

Carol Cahalane was probably the first person who ever used the word “transgender” around me. She knew how to pace conversations with adolescents. She didn’t push them to say something they weren’t ready to say, but communicated that she was available when you were ready to talk. She cared; that meant a ton. In terms of writing and a role model in the classroom, Fred Tremallo. He was one of those teachers who never looked at his roster very closely. When I showed up in his class my senior year wearing a coat and tie, he never realized that I hadn’t [always] been a boy. Early on, someone misgendered me in class and Tremallo said, “Why on earth would you think Alex is a girl?” After class, I explained the situation to him and he said, “I have no idea what you just told me, but I’m going to figure this out.” I had very open conversations with him and he urged me to write about my experiences.

What is your next book, The Story of Silence, about?

It’s a historical fantasy, a retelling of a 13th-century French poem in which a king decrees that women can’t inherit. As a result, a count decides to raise his daughter as a boy. Nurture and Nature personified argue with each other: “He’s mine, I made him what he is.” “She’s mine, I formed her.” There’s this understanding of gender that I found super-fun to play with.

What’s the thread that ties your work together?

I think when life is working well, one thing feeds another. Often times what I’m reading feeds what I’m teaching; what I’m teaching feeds what I’m thinking about; and what I’m thinking about feeds what I’m writing. By doing all these things, I nourish myself. There are some days when it absolutely doesn’t work, but mostly, if I can carve out a little bit of time to be creative, I’m happier on a day like that. But I think I could never be a writer who does nothing but write. I’m usually pretty happy to close my computer and go to class.

— Daneet Steffens ’82

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the winter 2020 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.