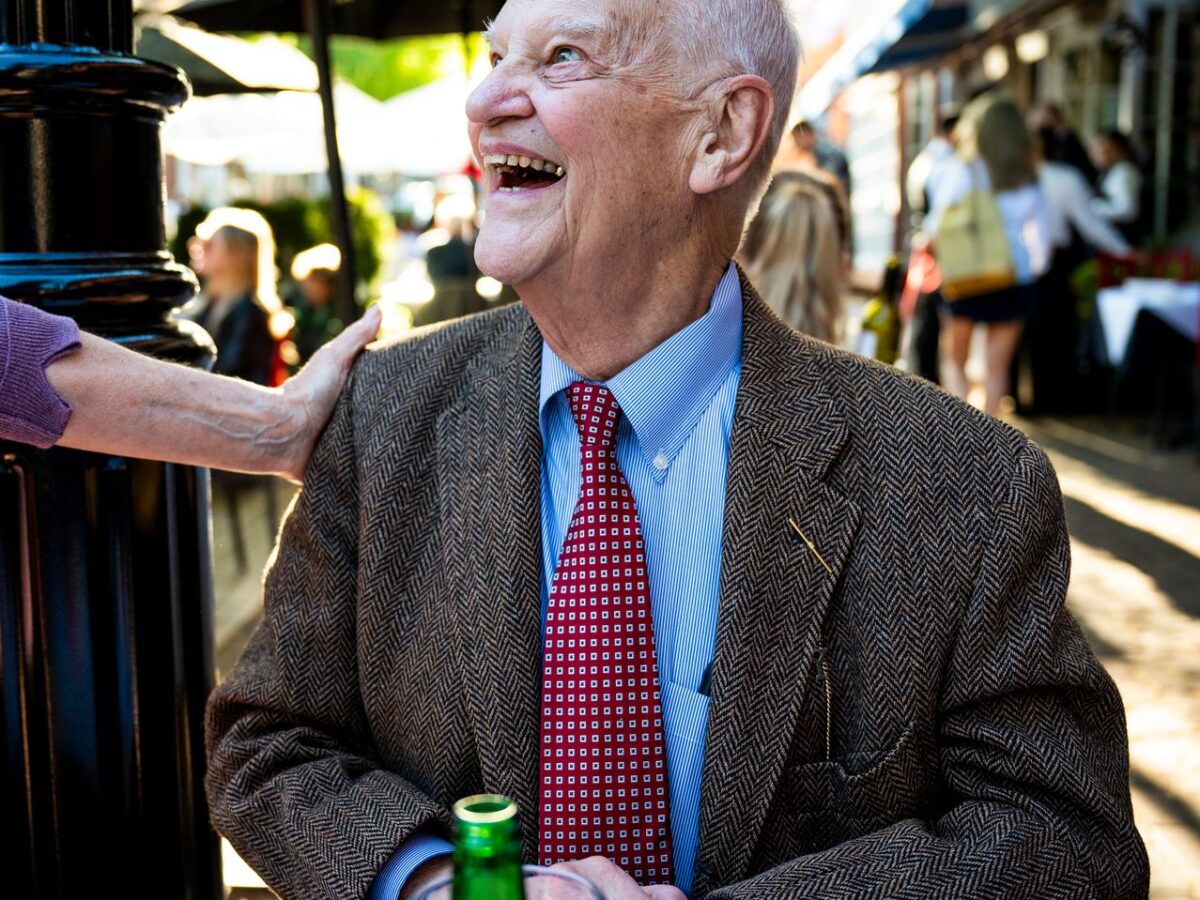

Peter Hutt ’52: ‘Never say no’

It was milk that brought Peter Barton Hutt to Exeter, and it was milk that launched his career in food and drug law.

The son of a dairy retailer just north of Buffalo, New York, Hutt became an Exonian thanks largely to the foresight of H. Hamilton “Hammy” Bissell ’29. A legendary admissions director, Bissell made sure there was a place for the young “milkman” on campus, even though Hutt failed not only part of the entrance exam, but also one of three summer school classes he was required to enroll in. “I don’t know what he saw in me, but he changed my life forever,” Hutt says.

Hutt found Exeter academically rigorous and demanding, but he says that was precisely what prepared him for the rest of his life. “I could never have accomplished what I have done if I did not have my Exeter education,” he says. “I owe everything to Exeter.”

That trajectory took Hutt to the law firm of Covington & Burling in Washington, D.C., where he spent his professional life, save a four-year stint as chief counsel for the Food and Drug Administration in the early ’70s. At the FDA, Hutt created the now ubiquitous nutrition label, defined the systematic regulation of over-the-counter drugs, was responsible for legislation related to medical devices, promoted regulations to define “imitation” foods, and brought the FDA into compliance with the Freedom of Information Act.

“I had to begin the first day overruling 100 years of FDA jurisprudence,” Hutt says with a laugh. “I just started dictating regulations day and night.” Getting things done is Hutt’s polestar: “I say, at least once a day, ‘Never say ‘no.’”

When he returned to private practice, Hutt, a father of four, added law professor and author to his lengthy curriculum vitae. It includes more than 100 appearances before Congress, 35 seats on biotech boards, election to the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Medicine, (now the National Academy of Medicine), and serving on a 1976 National Institutes of Health advisory committee that established guidelines for recombinant DNA technology.

At 89, he still teaches at Harvard Law School and is the lead co-author of the fifth edition of Food and Drug Law: Cases and Materials, which he has been co-writing since 1980, when only two law schools nationwide offered courses addressing the subject. “I said we’ve got to do a casebook so we can elevate food and drug law to an academically respected and important area of law,” he says. “It should be taught everywhere in the country.” Today it is — a professional legacy that delights Hutt.

Although he calls himself the “classic example of the law of unintended consequences,” there was a time when practicing law was not in his plans. His post-Exeter journey took him to Yale, where he joined the Navy ROTC and expected to serve in the Navy. An honorable discharge derailed that dream and he matriculated at Harvard Law. In his third year there, he says, his father began “pestering me with questions about food law.”

Fortuitously, Hutt saw a small written notice that the FDA’s chief counsel would be lecturing on campus, so he went in search of information for his father. The chief counsel offered not only answers, but also a fellowship to an NYU master’s degree program to study food and drug law. “I always ask, where would I be and what would I be doing if I hadn’t seen that notice?” Hutt says.

He spent the year at NYU “having fun” researching English food and drug laws from the Magna Carta to 1800 before boarding a train in 1960 for D.C., where he began knocking on doors. One belonged to a partner at Covington & Burling, then home to the largest food and drug practice in the city, with a mere three lawyers in the field. The partner, disdainful that Hutt hadn’t been on the Harvard Law Review, asked what he had done instead. “I said, ‘I published an 80-page article on federal milk marketing orders,’” Hutt says. “It turned out he knew a lot about milk marketing orders, but I knew more than he did. Four days later, I had the job offer.”

Other than the FDA interlude, Hutt has been practicing food and drug law at Covington & Burling ever since. He says he’ll think about retiring when he hits 100 — his mother lived to 107, so he feels the odds are in his favor — but he’s in no rush. “Why would I want to go grow roses when I can continue to do things?” he says. “I hope I go as I am finishing my last footnote.”

— Sarah Zobel

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.