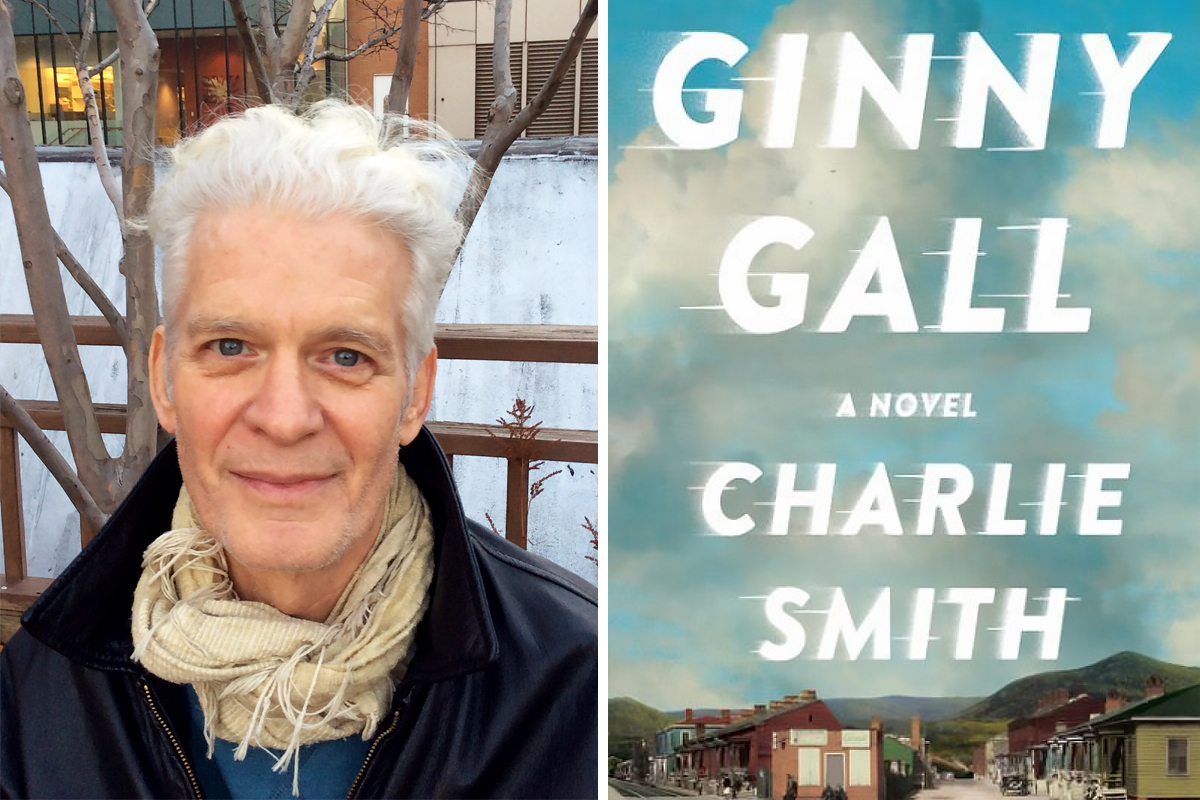

Charlie Smith

A Conversation with Charlie Smith ’65

The novel Ginny Gall, by Charlie Smith ’65, is both beautiful and harrowing. Smith, the author of eight novels, a book of novellas, and eight books of prize-winning poetry, tells the story of Delvin Walker, an African-American born in Tennessee in 1913. Young Delvin loses his mother when she flees their home after being accused of murder; is taken in by the kind and literate Cornelius Oliver; has to hightail it out of town after a skirmish with a white boy; and rides the U.S. railroad system in a bid to find a home, a place, his life. The novel sprawls across the America of Jim Crow and the Great Depression, steeped in the segregation, violence and destitution of the era, while vibrantly capturing the making of a man — and a writer.

Q: This could have been a novel about the breaking of a man, but you took it in a different direction. Where did this story come from? How did you decide where it would go?

Smith: Well, I’m not really a writer who forecasts his novels; I just start off writing. But this novel does have a kind of faint template: There are certain skeletal bones that reference the Scottsboro Boys in Alabama in 1931, nine young black men who were pulled off a train, accused of raping a couple of white women and thrown into prison. Those facts were more than I usually have to go on when I start writing.

One of the things that I wanted to do was write an imagined biography of a young man in peril in the South, the extreme difficulty that someone can find himself in — not of his own making — and how he responds to it. As far as the character being a writer, it wasn’t something that I thought of before I started the book, but as I moved along, I found myself interested in the side of Delvin that would culminate in someone who was becoming a writer. So I went along in that way, and that’s what followed.

I generally write prose tragedies — I’ve been writing them for 30 or 40 years. But part of what I decided to do when I was imagining this book was [to try] to write a book that didn’t culminate in tragedy. Or not that only. To make a road of troubles and pain and confusion but always with a snaking bright line through it to amendable possibility and freedom, or the chance of them.

Q: I’m interested in the idea that you didn’t plan on Delvin being a writer, because he was such an early reader: His mom takes pride in his literacy and he tells her, “It’s like I can tell the secrets now.” I took it as a lovely indicator that to be a writer, you’ve got to be a reader. But you didn’t plan for that?

Smith: Many readers are not writers; it doesn’t automatically follow. But someone who was smart was more interesting to me than someone who was not smart. So having this particular character and an interest in this particular character’s development — as a man of intelligence and as a man with the ability to see and be aware of things, to observe — that was what was part of it.

Q: And that’s something that comes through so palpably, the way you capture Delvin’s excitement and curiosity. Your language reflects that, and it doesn’t change when things take a darker turn. Even the bleakest parts of the book had this sort of light shining on them because of the way you used your language. Did you maintain that language to show how Delvin’s mind works?

Smith: Some of that is simply the way I write. I write pretty dark books — but this one is very light-spattered despite all the trouble and grief—it’s kind of a square dance compared to the books I usually write. But the juxtaposition of dark and light is an important part of how I approach a novel, and some of these decisions are intuitive decisions, they’re not something that I organize ahead of time. So the lightness you’re referring to is somewhat characteristic of how I write novels, but it’s also characteristic of this particular person — Delvin Walker — of how he experiences life.

I think what is steadfast and kind of wonderful about him is that he has a quality in him which is not just some kind of dumb adherence to a plan, or some stubbornness or even some kind of roguish wiliness that lets him slip the noose time and again. It’s something deep in his own heart that is a kind of lightness, or at least he sees a light. It’s not something that he holds on to as one would hold on to part of a religion or something like that, but a part instead of humanness that is naturally evoked in him — what would be called character, I guess, and what literature itself expresses, which is, in turn, the moral reliance that we find in literature.

Q: This book is steeped in a universal element, the recognition of the absolute necessity of being able to connect with others, whether it’s through Delvin’s experiences in prison, or his conversation with the old Confederate who says, “It’s good to get the human touch as often as you can.”

Smith: Yes, well, that’s interesting to Delvin, that’s something that he found out and came to know. And I think part of it was that he was a boy who became a man who had lost his mother at a very young age in a kind of violent way — she was there one moment and then she was gone, and there was no way to contact her. That loss was a powerful part of his life throughout his life, and probably would have something to do with him being willing to reach out to others, to want to seek a connection that had been lost to him in a very terrible way.

Q: When did you start writing both prose and poetry?

Smith: I started writing stories when I was a young boy, but I started writing poems when I was at Exeter. A lot of what Exeter’s English classes consisted of was being assigned some kind of story to write just about every week. That routine of having to write stories was a great help to me. I was pretty buffaloed by studies of grammar and things like that, which Exeter didn’t do much of — it was mostly reading books and writing, and that suited me wonderfully. And I had a class in which we were assigned to write a poem every week and I became very interested in that. When I discovered poetry — through a very ordinary anthology that we had freshman year at Exeter — I was just knocked out. It was just so great. Up until then the best thing in my life had been sports; I was a wrestler at Exeter. That poetry class gave me the sense that it was possible to actually write a poem, not just read one. I think I was the first one asked to put his poem on the blackboard for the first assignment and I put on a four-line poem about the rain that the class had quite a laugh about.

Q: That was your first appreciation as a poet?

Smith: Yes, that was the first: the laughingstock. They laughed because it was so terrible! Still, it didn’t set me back.

— Daneet Steffens ’82

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the winter 2017 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.