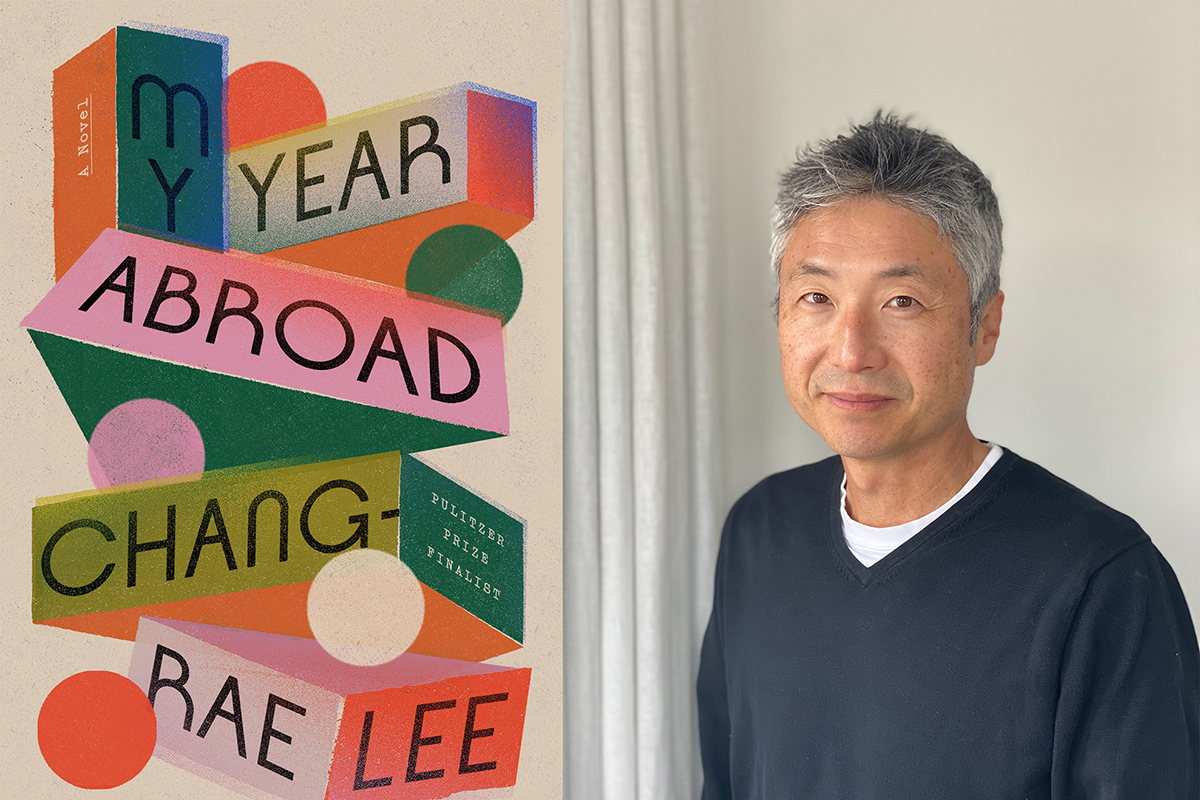

Chang-rae Lee

Chang-rae Lee, whose family came to America from Korea when he was 3, published his first novel, Native Speaker, in 1995. In the 25 years since then, he has continued to use his writing to explore the themes of immigration, assimilation, Korean history, the American Asian experience and dystopian America. His work has garnered multiple honors, including the Heartland Fiction Prize, a PEN/Hemingway Award and the Dayton Literary Peace Prize. He is currently the Ward W. and Priscilla B. Woods Professor in the English Department and Creative Writing Program at Stanford University. He has just been given the Award of Merit for the Novel from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, for recognition of a writer’s lifetime achievement, and he was elected to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences in April.

Lee’s latest novel, My Year Abroad, tackles the myriad experiences of college student Tiller Bardmon after he meets the mesmerizing Chinese entrepreneur Pong Lou. The ensuing whirlwind of business politics, ineluctable family ties, immigration histories, glitzy casinos, wild surfing and a home-based supper club has a jazzier, more eclectic feel than his earlier narratives, but delivers the same provocative punch. We chatted with Lee via Zoom about this book, his teaching role and his memories of Exeter.

My Year Abroad is picaresque, serious, seriously funny and downright scary. What was your starting point?

It started with the character of Pong Lou. I had befriended this fellow in Princeton, and I was so taken by him and his life. He was my age, a newer immigrant — I wouldn’t actually call him Chinese American, I would just call him Chinese — and had multiple enterprises, small but significant, as well as having a day job at a pharmaceutical company. I loved his energy, his courage and his exuberance for the chase, that anything in this world was open to him if he applied himself. That was a kind of immigrant that I had not really been familiar with. My view of immigrants comes from a very different time in American culture. My family and I, we were mostly isolated, wary, often cowed, not because the community had malice toward us, but because of language issues, cultural issues. This fellow really inspired me. I decided to write a novel about him, a different kind of immigrant story.

How did the book take on its expansive shape?

Once I started to write this character, flesh him out, I realized I wasn’t going to be satisfied with just a ‘new-striver-immigrant’ story. I began considering why I was so enraptured by him. I loved the fact that he was not really rooted, but still very comfortable. And I realized that I needed another character in this novel, someone who was going to be taken up and inspired by this fellow. So I paired him with someone younger, someone who’s just on the brink of finding out lots of things about himself, who’s about to emerge into the bigger world.

Family and food have been major elements in your work. Did you know that this book was going to embrace those elements, too?

Not at all! I knew that Tiller and Pong would have a business adventure, that they would have some kind of product, some sort of mercantile activity, but I had no idea what that was going to be. Once I started to investigate-slash-create Tiller, I thought, “He’s looking to consume and taste, to just stuff himself with the world.” I realized that that was something that Pong could be into as well: maybe he has a product, maybe he has stores, maybe he has all these ventures that cater to people who are ravenously consuming. I then realized that this was going to be a book about visceral sensation. Tiller wants to taste the world, but, you know, there’s an unspoken pact there that the world will taste you back. For better or worse.

This book is packed with wordplay. Was it fun to write?

I never have fun in the actual act of writing, but I did enjoy afterward having written those words. I understood that that was part of the character and psyche of Tiller, that he had a lot of range, a lot of different sources for his language — high, low, popular, academic, rude, profane. I liked the idea that this palate of language was there, very wide, very colorful. It was something that I did not allow myself in other books because of their nature.

Why did you allow yourself to go there now?

In some ways, this is my most personal novel. There’s a melody to Tiller and cadence and rhythm — the way he thinks and expresses himself — that’s probably as close to mine as any character I’ve ever written. The other books are also me, but because of their characters and subjects, they employ a different kind of music. People would always be surprised after reading my books that I wasn’t such a dour, serious guy. This one is more in tune with who I am.

You’ve mentioned that Island of the Blue Dolphins was a childhood favorite. Is there some connection between that book’s main character, Karana, and your Victor Jr.?

Absolutely! And also, to Tiller. It’s not just about self-taught learning, it’s about the sense of being orphaned. Immigrants can feel a little orphaned in new cultures: I couldn’t go to my parents and ask for guidance — they didn’t even speak the language. You’re kind of on your own. I’ve always identified with kids who have to be this way, not strict autodidacts, but who are curating their selves — in education, culture, style.

Have your books helped you figure out your place in America?

No. I don’t feel any more resolved or sure about my identity than before I wrote Native Speaker. This is something I experience with my students, too: I teach an Asian American autobiography class and the students always think, “I’m going to take this class, write about myself and figure things out.” They soon realize that there are so many more areas, facets, places in their identities and in their lives that they have not yet explored or considered or reckoned with, that it’s just about continuing to build self. I certainly feel that way; I’m still building my identity.

How did Exeter impact your life?

Sitting around that Harkness table, I learned to not be satisfied with the first best answer. As a writer, I always have an immediate idea for this sentence, this character, this description, but Exeter was the first place that really trained me to be open to other answers or responses. It was always surprising where enlightenment came from, in those classrooms. Sometimes it would be from a quiet student, sometimes it was the teacher, often it was from the folks who always spoke up. But it was always unlikely and surprising and cool.

Do you duplicate that approach in your classes?

I absolutely do. I tell my students, “I’m just one of you. I hope that you will all guide the discussion to wherever it’s going to go.” I really loved that about Exeter, that most of the teachers weren’t strict or parochial in what they were going to discuss. And isn’t that what an artist, a writer, needs to learn? People always ask me, “Do you plan out your books?” and I say, “Well, only in the most general way.” If it has any life, if it has any vitality, it’s only because you discover those things along the way.

—Daneet Steffens ’82

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the spring 2021 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.