A Hero’s Life

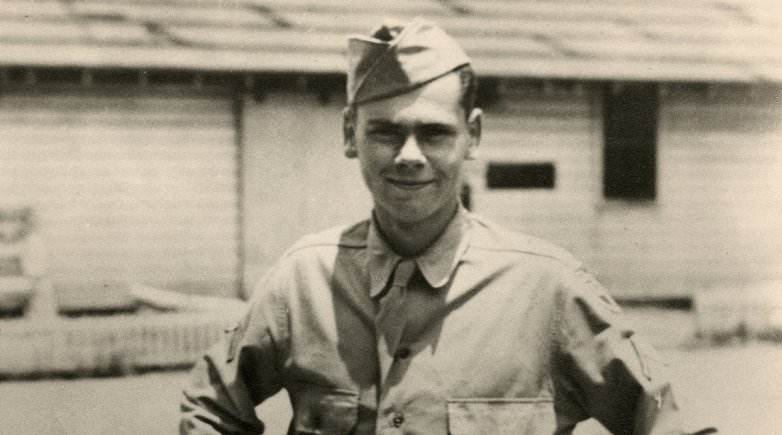

Stephen Crabtree ’42 inspires a new financial aid fund.

There were approximately 300,000 American combat deaths in World War II. Among them was Stephen Mason Crabtree, Exeter class of 1942. These tragedies are remembered with statues in town squares and on memorial walls across the country. Steve’s name appears in Exeter’s Assembly Hall, in Dunster House at Harvard, in Grace Episcopal Church in Newton, Massachusetts, and on an engraved brick outside the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

Each of the losses represents a unique human story, most of which, seven decades later, have passed into history. An epitaph at the Gettysburg Museum and Visitors Center perfectly captures the effects of these individual tragedies. Referring to the great number of deaths on both sides during the Civil War, it reads:

“Every name is a lightning stroke to some heart, and breaks like thunder over some home, and falls a long black shadow across some hearthstone.”

Such was the strike inflicted on the Crabtree home in Newton Centre, Massachusetts, when news of the combat death of 20-year-old Stephen, the family’s youngest, arrived in April 1945.

Preserving the human story of Stephen Crabtree is the motivating factor in establishing the Stephen Mason Crabtree, Class of 1942, Financial Aid Fund at Phillips Exeter Academy. Hallmarks of his brief life were leadership, patriotism, duty, and quiet accomplishment, all traits that came to full bloom in his Exeter years.

The “Class History” section of the 1942 PEAN traces the changes in aspirations of students who’d entered the Academy in 1938, overlaid with events unfolding in Europe, where expectations of peaceful lives become radically altered in the course of the ensuing four years.

Amid World War II, Exeter students in the winter of 1942 were conducting blackout and building evacuation exercises. Courses in first aid and airplane trigonometry were offered. New students arriving from England reported the suffering and destruction in their homeland. Debate societies strongly disapproved of Hitler’s policies, reflecting the prevailing campus sentiment of the day.

Such was the environment from which Steve graduated, and which he found at Harvard, where he enrolled as a premed student. An honor student at Exeter, Steve achieved the same distinction at Harvard. Nonetheless, the war pulled deeply at his sense of patriotism, and he left college to enlist in the Army at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, in February 1943.

He chose to serve in the most basic manner — as an enlisted infantryman. It wasn’t a glamorous choice, and Steve would have had many easier and safer avenues available. He would not have been drafted because he suffered from poor vision, but he memorized eyesight examination tables in order to pass the exam. And as a premed student he could have exempted himself, as the country expected a shortage of physicians. But he persisted in a cause he believed was right.

Persistence is a trait Steve also displayed at Exeter. He was a gifted student, but the Academy challenged him. During his first visit home, his father asked him what he had learned. Steve said, “I learned how to work and I learned how to worry.”

As an upper, Steve applied to an advanced biology course being offered at Cornell that summer, but he was rejected on the grounds that the class was intended for advanced college students who had already excelled in higher-level biology courses. Steve appealed to his Exeter biology instructor, who, in turn, contacted Cornell and suggested that they reconsider Steve’s application, which they did. Steve completed the summer course and finished at the top of the class. Then, in a typical display of adventurism, he rode his bicycle from Ithaca, New York, to his home in Massachusetts.

Leadership and earning the confidence of his peers were also characteristics Steve evidenced at Exeter when, in 1939, he was elected to the school’s Senate, a position he had not sought, but in which he served.

By all accounts, Army life agreed with Steve. He was first assigned to the 10th Mountain Division at Camp Hale, Colorado, then to the Army Specialized Training Program at the University of South Dakota, and, finally to I Company, 386th Infantry Regiment, 97th Infantry Division in 1944. Initially, the 97th was intended to be part of the invasion forces for Japan. Training was conducted along the beaches and seaside cliffs in southern California. However, due to the unexpected losses suffered in the Battle of the Bulge, the 97th was redirected and was deployed for Europe in February 1945.

Steve was one of 14,000 enlisted personnel in the division, and he became one of its 188 combat deaths on April 10, 1945.

Disembarking at Le Havre, France, in February 1945, the 97th traversed France and Belgium into Germany, through Aachen, and on to the Rhine, all war-torn areas.

On April 3, he wrote his mother, “Dear Mom, I am in [Germany], and as I am in the Infantry you can imagine what I will be doing. Right now things are happening so fast that it is difficult to keep the correct mental perspective.” Cheerfully, on April 4 he wrote, “I am fit and well and think of you and home always. Send some chow!”

But later he wrote, “It isn’t until you get over here and start playing for keeps that you realize what they have done, and are still doing to you personally.” He refers angrily to “privation, pain, and suffering.”

Steve’s unit eventually came under enemy fire at Neuss, near Dusseldorf, Germany. They crossed the Rhine south of Bonn and made their way north to the Sieg river. Steve volunteered for hazardous night patrols across the Sieg, locating enemy positions.

I Company went on offense on April 10, crossing the Sieg river on small rubber boats and proceeding northwest with the goal of taking the city of Solingen. They were a part of the Ruhr Pocket, an operation in the Ruhr area intended to destroy the last of Germany’s industrial capacity.

I Company advanced northwest through up-sloping woods onto an open plain at Ober Hulschied, a small crossroads, when they hit a German strong point and were attacked. Twelve Americans were wounded and four were killed — including Steve.

He was killed instantly by a shell burst from an 88-mm cannon. Frank Lazlo reported that both he and Steve hit the ground, almost side by side, at the same time. There was an explosion. Frank got up and Steve didn’t. Two other fellow soldiers, Paul Piccard and Jim Moore, saw Steve lying dead on the ground with a hole in his helmet. A few weeks later, the war in Europe was over.

At the time of his death, Steve was doing exactly what he wanted to be doing: playing a role in a just and important cause. By choice he was not a bystander, but neither was he ambitious for notoriety. A monument at the Antietam Battlefield is engraved, “Not for Themselves but for Their Country” — a definitive American creed that Steve carried into harm’s way in Germany in 1945.

The first in I Company to receive the Combat Infantryman Badge, Steve was awarded the Purple Heart posthumously. His battalion commander wrote that “his excellent traits of character set the example for all the men of his organization” and that “he was a man who wasn’t satisfied with the best; he wanted to do better.” His company commander wrote that “[Steve] was one of the best soldiers I commanded. He was very well liked by all his comrades and a natural leader.”

Stephen Mason Crabtree was born on August 30, 1924, in Brookline, Massachusetts. His father, Dr. Harvard H. Crabtree, was a prominent urologist in Boston. Dr. Crabtree rose from humble beginnings in Hancock, Maine, to graduate summa cum laude from Harvard College and Harvard Medical School. He lamented that his years at Harvard were very difficult, as he lacked the preparation enjoyed by most of his classmates. Wishing a better collegiate experience for his own sons, he enrolled Harvard H. Crabtree Jr. (class of 1937) and Stephen at PEA.

Stephen Crabtree was my uncle, and Dr. Crabtree was my grandfather. Steve died before I was born. As a boy and young man, I spent many weeks and months living at my grandfather’s house at 1029 Beacon Street in Newton Centre. I learned much about my Uncle Steve from my grandfather during those times. I have seen the indelible grief such a loss inflicts on a family.

Later, I had several occasions to attend I Company reunions and to meet and visit with several men who served with Steve. To a person, they confirmed every one of Steve’s traits and characteristics that his father had conveyed to me years earlier. I visited the area and site of his death on two occasions. On the second visit, in 1995, I was accompanied by David Robinson, a sergeant in I Company.

Interviews during the 1990s with several of Steve’s Army colleagues consistently portray him as a regular guy, one of the team, even though the rest of the team didn’t have backgrounds of Exeter and Harvard. He fit in. He was liked, respected and trusted. Similarly, Steve enjoyed the camaraderie of enlisted life, as evidenced by him repeatedly declining offers to enroll in Officer Candidate School. He felt a loyalty to his peers.

Steve’s mother wrote to the Academy in May 1945: “We are increasingly grateful to you all at Exeter for giving Stephen his happiest years. The many interests and plans, fostered by association with friendly, understanding teachers and comrades, filled him with a zest for life and appreciation of solid worth wherever found.”

Archival material related to this narrative is maintained at PEA. Annually, on the anniversary of his death on April 10, the Academy will fly the American flag that accompanied Cpl. Crabtree’s remains as they were transferred home after the war.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the spring 2018 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.