John Bascom Heath: A Memorial Minute

John Bascom Heath was born in 1923 in Lawrenceville, New Jersey to Mary Darwin and Harley Willis Heath. Jack grew up on the campus of the Lawrenceville School from which he graduated and where his father taught science for many years. His undergraduate career at Yale was interrupted by a three-year stint in the military where he rose to the rank of Staff Sergeant in Patton’s Third Army and earned the Bronze Star. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Yale in 1946 and began his teaching career, first at Exeter in 1947 and then at Germantown Academy for one year, before returning to Exeter for good in 1949. For nearly 40 years, Jack certainly was a force for good at the Academy.

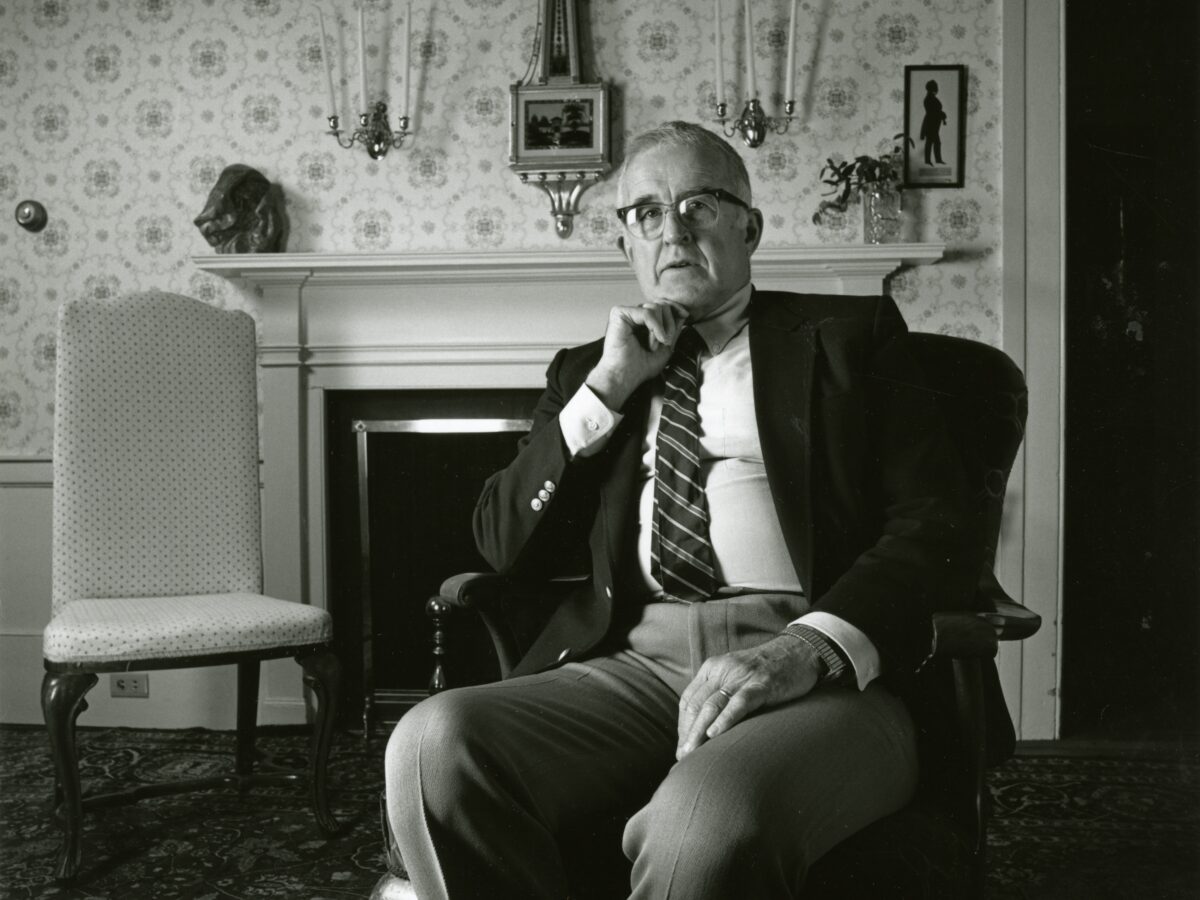

Principal Kendra Stearns O’Donnell described his exemplary service at Exeter as “rooted on traditional school ground: the classroom, the dormitory, the playing fields.” He was the “consummate school man.” History instructor Jack Herney recalls the figure Jack cut on campus: with his “rumpled sartorial style. . . he looked the picture of the absentminded, disheveled but wise savant.” Heath once wrote that “teaching, coaching, and doing dorm and committee work are demanding; but we do get good vacations, and ought to work hard in term time. The happiest people,” he continued, “work the hardest, or, to put it a better way, are the most involved, and I think the involvement causes rather than results from the happiness.” Jack was certainly involved at the Academy and in the Exeter community at large. By his own accounting, then, Jack was a very happy man, always looking to “put” the world he inhabited “a better way.”

Jack’s numerous titles at the Academy reflect the range of his contributions. He was appointed the Thomas S. and Elinor B. Lamont Professor of English. He served as English Department Chair from 1973-1983, the Dean of Faculty from 1983-1987, and Acting Principal for one year when Principal Stephen Kurtz took a sabbatical. From 1956-1971 he was varsity head coach of the soccer team, where his wing players would often hear him shouting “Gotta have it” from the sidelines, pushing them to hustle after every ball. He also coached basketball and baseball, serving as Commissioner of Club Baseball from 1962 1973. He spent the 1967-1968 school year teaching in Barcelona, Spain with the School Year Abroad program. Jack also served as adviser to the Exonian and on countless committees: the Academy Planning Committee, the Faculty Affairs Committee, the Appointments and Leaves Committee, and the Student-Faculty Committee on Student Life, to name just a few. He received the Faculty Prize for Academic Excellence in 1967 and the Rupert Radford Faculty Fellowship Award for distinguished and faithful service in 1988. It is no wonder that Jack was also an honorary member of the Class of 1952 and was recognized in 1991 with the Founders’ Day Award.

Jack was also a distinguished public servant in the town of Exeter, and he was once called “the most respected man in town.” He and his wife Patty ran the Cub Scouts for two decades. Jack brought soccer to Exeter, founding the first youth soccer program and introducing it to Exeter school system. He was a School Board member, spokesperson for the Exeter Voter League, president of the Rockingham County Trust, secretary and board member of the New Hampshire Farm Museum, and Secretary of the Exeter River Watershed Association. He served in the New Hampshire House of Representatives, as well.

For many summers he ran Kamp Kill Kare, a summer camp for boys in St. Albans, VT, where his father had also worked.

After those summers in Vermont, from 1979-1983, Jack worked as director of the Exeter Writing Project, a precursor to many of our summer institutes for educators. Barbara Ganley, an attendee who was also a former student of Jack’s at the Academy, describes his impact in that summer program:

And so once again I became his student, but this time of his secrets to teaching. How unexpected. How remarkable. He likened teaching to coaching sports, helping students learn to love the practice, to open up the sentence itself to learn about the full essay. Just as a pitcher throws pitch after lousy pitch day after day to get any good – a writer must stand out in that field to be struck by lightning.

On the practice field of Jack’s English classroom, students encountered a teacher who pushed and encouraged them to stand out in that field day after day. He held his students to high standards, and his compassion guided them to become more competent writers and more perceptive readers. Philip H. Loughlin ’57 credits Jack for instilling in him a lifelong love of literature. And Tom Gross ’70 shares that Jack “was always very kind to me and seemed to take a genuine interest in trying to help a not-very-good student.”

Reflecting on her time as a Prep in Jack’s English class, Barbara Ganley shares: “Without him, I wouldn’t have made it through my Prep year much less go on to teach writing or to become a writer myself. . . . [A]s I sit at my writing desk, I remember his urging me to reach for a sentence as clean as a bone. To work for it. And of his quiet encouragement that of course I could do it.” Vinson Bankoski ’81 recalled similar guidance.

“Mr. Heath’s English class,” he writes, “helped me identify what Exeter was really about and why I was really there.” After reading aloud in class a draft of a paper he had written about his grandfather who recently passed away, Vinson took in Jack’s feedback and sat down to work at his revision:

And so once again I became his student, but this time of his secrets to teaching. How unexpected. How remarkable. He likened teaching to coaching sports, helping students learn to love the practice, to open up the sentence itself to learn about the full essay. Just as a pitcher throws pitch after lousy pitch day after day to get any good – a writer must stand out in that field to be struck by lightning.

Jack’s son Sam relates the experiences of author Dan Brown ’82 his Lower year in Jack’s class. On Dan’s first composition, alongside the red C-minus, Jack had written in all capital letters “KEEP IT SIMPLE.” This was Jack’s “essential philosophy,” Sam explains. You can hear echoes of that philosophy each fall when Dan Brown speaks to the Prep class about writing.

“Sometimes,” Jack wrote in 1956, “when a class is just right – the boys are attentive, even the silent member of the class has something to say, and the bell rings unnoticed, [I am] sure there is no better way to make a living.” Other former students recall Jack’s sense of humor. David Lamb ’58 visited campus on a whim while passing through in 1981, twenty-three years after he had been kicked out during his senior year for running a gambling ring in his dormitory. David, a successful journalist at the time, was invited to sit in on a faculty meeting. He writes: “Several heads, now covered with gray hair or little hair, turned toward my seat in the back of the room. ‘Why, Lamb,’ said my former English teacher, Mr. Heath, as though he had seen me only yesterday, ‘I thought you’d be at the dog track today.’”

That sense of humor served Jack well in his administrative roles. Former counselor, Mike Diamonti, remembers his interview for a faculty position in 1983: “Knowing I had no prior boarding school experience, Jack explained the core teaching, coaching, and dorm responsibilities. I replied that although I liked sports I had never coached and wasn’t sure I could take on that responsibility, even at the club level. Jack replied by saying, ‘there are only two things you need to know about coaching. When you win you say, coaching shows, and when you lose, you say coaching isn’t everything.’

Former Chief Financial Officer Jim Theisen spoke about working with Jack in the year when Principal Steve Kurtz was on sabbatical, leaving the Academy in Jack’s capable hands. Jim went to Jack on a delicate personnel matter. “Jack listened intently and confirmed it was a big issue,” Thiesen explains. “He said let us both sleep on it and confer tomorrow. I left and slept like a baby knowing it was now on his plate. Returning the next day I could tell him the problem resolved itself and did not need his help. He said, ‘Good, I forgot you talked to me.’ It was the best MBA management lesson I got…and from an English teacher!” Jack Herney confirms that Jack’s style was to “never rush into any decision. He made decisions based on the evidence he had at hand, and he didn’t look back or second-guess himself.”

A father-figure to many students and a mentor to many colleagues, Jack was also a devoted husband and father to four boys. In 1947, he married his beloved wife Patricia Espy Kreutzer. All four Heath sons (Jeffrey ’67, John ’70, Samuel ’72, and Harley ’75) attended the Academy and played varsity soccer. Jack served as dorm head of Wheelwright Hall for twenty-three years. When Jack dug out a piece of lawn in front of the faculty entrance to plant irises, he may have been the first faculty member to plant a garden on campus. Colleagues marveled at his green thumb and stewardship of natural spaces, qualities that guided his work on the first piece of property he ever owned – a house and nine acres in Newfields where the family moved in 1968. “People would be amazed,” Jack once told his son Sam, “at what happens when you put a seed in the ground and you water it.”

One of the seeds that was planted for Jack in his youth was the power of community. He lost both of his parents by the time he was eighteen, and the Lawrenceville School community was there for him. As you have heard this morning, Jack brought his full self to serve the Academy community. One Thursday morning as he neared retirement, Jack opened up to the community in a Meditation delivered in Phillips Church on December 10, 1987. He spoke of his relationship with death, referring to himself throughout in the third person:

I have a dear friend who all his life has known that he is going to die. At age twelve he learned that mothers die of breast cancer, and at eighteen that fathers die of strokes. By the time he was eighteen, two of his high school classmates had already been shot down flying in the Canadian Royal Air Force. . . . A man in his sixties is a fool not to realize he is going to die. Most of the time my friend. . . knows it logically but not emotionally. He does not constantly or often think about death in the abstract or even of his impending death. For example, on the day he suddenly and soberly realized that he had lived longer than his father, he went out into his woods as usual, as he had done four or five times a week for ten years, even in winter, and worked for an hour or two by himself chain-sawing red-oak logs and hauling them out by hand one at a time to the sunning place. He is a quiet but serious woodsman—a pure amateur who believes in self-sufficiency without land-abuse, and in silent, solitary meditation….. But now when he is about to go out in the woodlot to cut and haul firewood he tells his wife that he is going out. Or, if she is not home yet, he leaves a note on the clipboard in the kitchen: ‘in woods sawing 2:45.’ He could not have done that ten years before. And even now he thinks it more considerate than practical. She worries about chainsaws.

Whether he was caring for his family, students, colleagues, town, country, or for the land, Jack committed his whole self. He believed, Sam tells us, that we “must accept people as they are” and “hold everyone,” including ourselves, “to the highest standards of integrity.” In closing, an image of Jack moving between the work that he loved seems fitting. This, too, comes from his son, Sam: “How many times did I watch him come home between classes, switch into muddy overalls, and hoe a few rows of beans or take down a couple of trees before putting back on his khakis, tying his bow tie, and returning to campus for a 5:25 class. He never raced, he puttered, with purpose, and he finished what he began.”

Jack died May 28, 2018, at the age of 95. He is survived by his sons Jeffrey, of Ann Arbor MI and Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso; Samuel, of Exeter, with Sandra del Alczaar and their children Aymara and Santiago; and Harley, of Wolfeboro NH, with Stacey Lessard and his children Rory and Addie.

I move that this Memorial Minute be spread upon the minutes of the faculty and a copy sent to the family.

Respectfully submitted,

Brooks Moriarty

This Memorial Minute was first published in the spring 2025 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.