Public Service

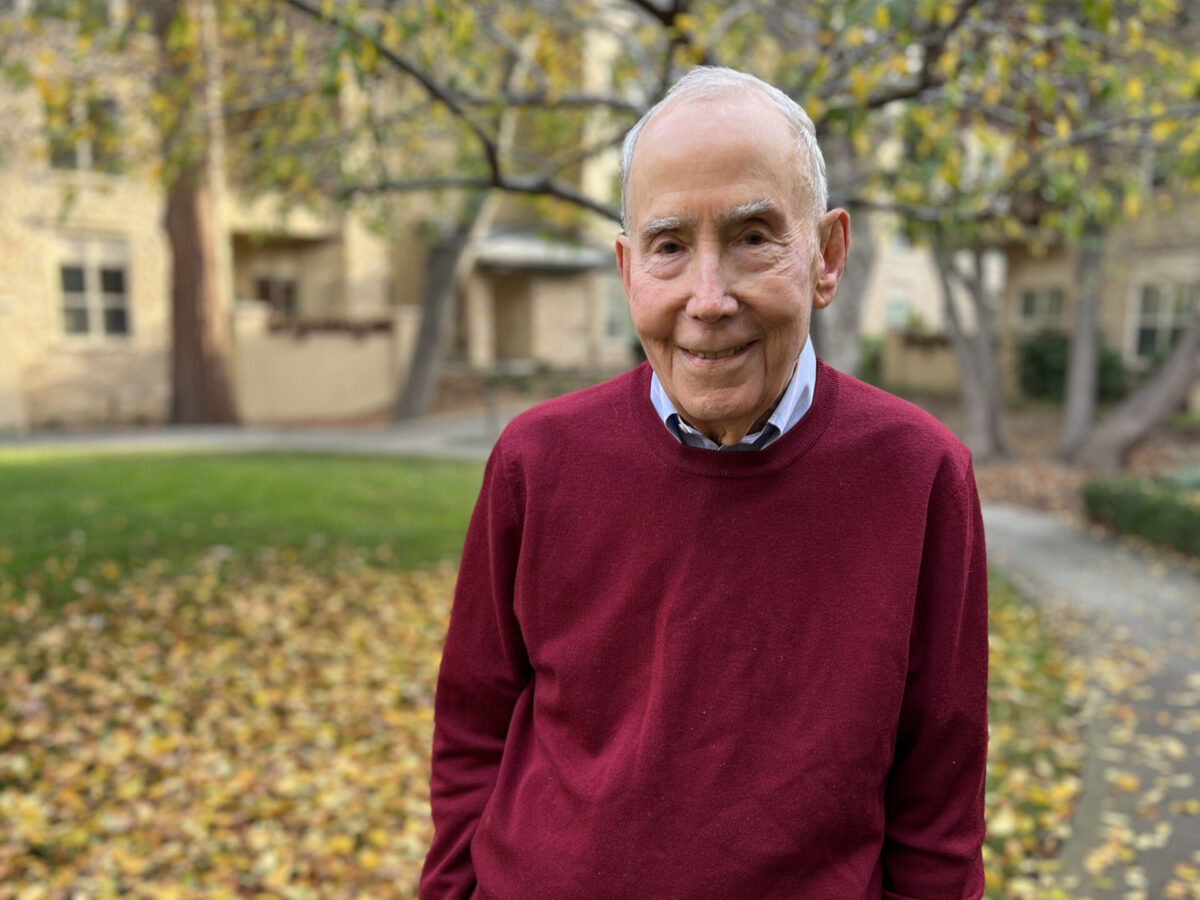

A conversation with statesman, educator and attorney Thomas Ehrlich ’52

Thomas Ehrlich ’52 has served in the administrations of six U.S. presidents — including as the first president of the Legal Services Corporation and the first director of the International Development Cooperation Agency, reporting directly to President Jimmy Carter. He was also dean of Stanford Law School, provost of the University of Pennsylvania and president of Indiana University.

He has authored, co-authored or edited 15 non- fiction books, written two novels and is finishing a third, Jewels.

We spoke with Ehrlich, 91, about his memoir, Learn, Lead, Serve: A Civic Life, released in December.

You talk about mentorship throughout the book. Is there one mentor who had the largest impact on you?

My father. We were as close as father and son could be — we skied together, played together, read novels together. I can still remember reading The Once and Future King with him. He was always there, always supporting me and a model of what a father, a husband and a caring civic person should be. Other mentors have had a shaping influence on my life including Judge Learned Hand, for whom I was a law clerk, and Under Secretary of State George W. Ball, for whom I was a special assistant during the escalation of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

You tell a story about your grandmother giving you a biography of Louis Brandeis, an attorney and associate justice of the Supreme Court. Did that shape your decision to use your abilities for the public good?

Yes, I still have that blue-bound copy of that biography. Brandeis was a great public servant in the best sense. And service was an important part of Exeter for me as well. In my memoir, I call Exeter my ‘best education’, and that’s not hyperbole. Harvard and Harvard Law School were wonderful, but Exeter and the dedication of the teachers 24/7 to their students, of whom I was privileged to be one, was just amazing and transformative for me. Non sibi was at the core, and that really shaped me — it shaped my sense of who I am, how I want to relate to the world around me. I think of the times when I have had the good fortune to be involved in public service, and I really owe much of that to Exeter. This is what Exeter expected of us as students — to think not just about ourselves, alone — and that’s just the way you behaved. When you learn that and behave that way, or try to at least, as an adolescent, it’s built into your character as you grow up and grow older.

It seems like Exeter shaped you emotionally, as well as intellectually.

It did very much, yes. Intellectually, it certainly did in history and in English. We wrote a lot and I’m still writing now. I’m 91 years old, and here I am, writing away, working on my third novel. Exeter is where I learned to read and write, to write and enjoy.

For your Harvard thesis, you researched a survey of family farmers that was done by the Department of Agriculture. You say it was an early awakening for you to the importance of public policy shaped by public opinion. How does it frame the way you look at what’s happening in our country today?

I’m deeply disturbed by what’s happening now. The Trump administration’s assault on our democracy is terrifying. I taught for many years a course called “Democracy in Crisis” at Stanford, so I’m familiar with past crises. And of course, we did have a civil war. This is not a civil war, but I am devastated by seeing what’s happening in terms of an elected president seeking to destroy much of the social fabric of our country, as well as its leadership in the world. Since I oversaw the Agency for International Development, its destruction is a particular blow to me. Millions of people are dying because of that action.

Do you see a future way of managing our way out of this?

I have hope. I quote one of my professors, Sam Huntington at Harvard, who wrote a terrific book American Politics: The Promise of Disharmony. He ends by saying,“Critics say that America is a lie because its reality falls so far short of its ideal. They are wrong. America is not a lie; it is a disappointment. But it can be a disappointment only because it is also a hope.” I have hope. I believe we will have a pendulum that swings back toward the middle, that those in Congress will say, “We’ve got to stand up and stop what’s happening.” But the carnage that’s happening

— America’s place in the world will never be the same.

In your many roles in six administrations, was there one in particular that has stayed with you?

Well, they all stay with me. But the one that shaped me most was the Legal Services Corporation, because when I became dean at Stanford Law School, I had no real idea that 40-plus million poor people had no access to justice. It concerned me, which is why I thought, “If I can have a chance to do something about that, I want to do it.” I spent three-plus years listening to poor people all over the country, hearing their stories of how a crisis would happen if they didn’t get a Social Security check or got evicted, and how important it was to have a lawyer, and what a difference that person could make by listening and devoting their lives to helping poor people. That also shaped my approach to others less fortunate and my character.”

You’ve become particularly focused on instilling young people with awareness around community service, public service and civic learning. Do you think that that’s our most hopeful way forward?

I do. I think it’s essential. That has been my passion since the mid-’80s when I was at the University of Pennsylvania, but it’s certainly increased in that the only significant organizations outside of the universities that I’ve helped to run are ones dedicated to preparing college students to be actively, responsibly engaged in public policy and politics. If we don’t do a better job of that, we’re going to suffer more. It’s important not just to serve in a community kitchen, but to ask: “What public policy changes are needed so that community kitchens are no longer necessary?”

— Daneet Steffens ’82 is a books-focused journalist. She has contributed to the Bulletin since 2013.

This article was first published in the spring 2025 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.