History

History

in Focus

Examining the Academy’s connections to slavery and its path forward

Her name was Dinah, and she lived with a man named Cuffee on the edge of the thick woodland that once covered the Academy fields, just steps from where The David E. and Stacey L. Goel Center for Theater and Dance now stands. In the mid-19th century, the elderly Dinah made a living selling cake and ale to the boys who attended the Academy, as well as any others who made the pleasant walk from the center of town to Cuffee’s Woods, as they were known.

By 1879, when a local resident recounted his memories of Dinah and Cuffee in the Exeter News-Letter, the couple had long since died, leaving few traces of their presence behind. But Dinah’s story is worth remembering not only for its connection to the history of Exeter — the town and the school — and her role in the day-to-day lives of some of the earliest students at Phillips Exeter Academy. As a young woman, she was one of several individuals previously acknowledged in Academy histories to have been enslaved by Exeter’s founder, John Phillips.

In January 2020, with the support of Exeter’s Trustees, Principal Bill Rawson ’71 announced the formation of a steering committee to examine the ties between Phillips Exeter Academy and the institution of slavery. At the time, he wrote, “The work contemplated by this charge will provide a more complete and complex understanding of the early history of our school, will expand the voices involved in helping us understand and tell that history, and thereby will advance the mission and values of our school and our commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion and a deep sense of belonging for all members of our community.”

But the COVID-19 pandemic delayed the committee’s progress. In May 2023, Rawson issued an expanded charge fort he Committee to Study Slavery and Its Legacy at Exeter, co-led by Director of Equity and Inclusion Stephanie Bramlett and Magee Lawhorn, head of Archives and Special Collections, and made up of Exeter faculty, staff, alumni and students. That fall, the committee embarked on the first phase of that charge, which included reporting on the known information about Exeter’s history and connection with enslaved people; developing recommendations for appropriate recognition to help the community understand this history; and collaborating with the Exeter Historical Society to incorporate the history of enslaved people in the town of Exeter.

“Telling these stories is a way to honor the people who made Exeter what it is today,” Bramlett says. “It’s powerful to know the stories of the people who came before us, and to consider the way their legacy shapes our current experiences.”

In undertaking this effort, Exeter joined a growing movement among educational institutions. When Universities Studying Slavery, a consortium led by the University of Virginia, expanded its membership to private high schools, the Academy signed up, as did peer schools including Andover and Loomis Chaffee. The consortium has more than 100 members in six countries, including Brown, Georgetown and Harvard.

Histories of the Academy have documented John Phillips’ ownership of several individuals during much of his life, including 1781, the year he founded Exeter with his second wife, Elizabeth. Although slavery does not appear to have been associated with the physical construction of the school and he was not an enslaver at the time of his death, “that [John Phillips] owned and kept slaves for at least a part of his life, with no thought of there being anything morally wrong about it, is a matter of record,” Laurence M. Crosbie wrote in The Phillips Exeter Academy: A History, published in 1923.

In 1743, Phillips married his first wife, Sarah Gilman, the widow of his cousin Nathaniel Gilman, who had owned and operated a general store. Sarah, who was 16 years older than Phillips, brought her significant estate into the marriage, including three enslaved individuals: Robin, Phillis and Dinah.

Among wealthy white New Englanders of his time, Phillips was far from unique. As historian Wendy Warren wrote in her 2016 book, New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America, by the early 18th century “slavery was embedded in the New England colonies, an accepted and familiar part of the society.”

Instructor in History Kent McConnell, a member of the Exeter steering committee to study slavery, says, “Many men of [Phillips’] stature would have owned enslaved persons.” He adds that many men would have similarly inherited themas part of their wives’ dowries, a common way of ensuring financial security at the time. “There’s so much profit being generated around chattel slavery,” he says. “It’s part of a global economic system that deeply reaches into the lives of the colonies in so many ways.”

As the Revolutionary War dawned, attitudes toward the institution of slavery began to change. “White enslavers are struggling — in varying degrees, obviously, but they can’t ignore the realities of the proclamation of ‘all men are created equal,’ ” McConnell says. Antislavery sentiment built across New England in the 1770s, and individual states — beginning with Vermont in 1777 — passed laws to restrict slavery.

Sometime in the late 1770s, Phillips most likely joined a growing movement among New England slave owners by manumitting, or granting freedom to, at least some of his enslaved people. By 1778 — three years before he and Elizabeth signed the founding documents of theAcademy — neither Phillis nor Dinah was part of the Phillips household. Crosbie wrote that town records show Phillips was taxed for two male enslaved people from 1778 to 1780, and for one from 1781to 1785. When he died in 1795, Phillips owned no enslaved people; his will stated, “I give to my man-servant (Slave I have none) such part of my wearing apparel as my Executor shall think fit.”

Among the untold stories the steering committee seeks to illuminate are the lives of the men and woman Phillips enslaved. From the Exeter News-Letter article and other contemporary accounts, we know a fair amount about Dinah’s later life and interactions with early Academy students. The historical record contains less information about the two other individuals Phillips acquired in the 1740s with his first wife’s estate. Phillis, described in Nathaniel Gilman’s will as“my Negro woman,” was most likely older than Dinah, who was described in that will as “the Negro girl named Dinah.” A Gilman family history later stated that Phillis was a gift to another Gilman relative in Yarmouth, Massachusetts, around 1771.

Information is notably lacking about Robin. Unlike Phillis and Dinah, he does not appear in the Gilman family genealogy but was probably enslaved by Phillips for more than three decades. Judging from Exeter tax records, Robin was most likely the last individual Phillips enslaved, and he was either emancipated or died around 1785.

A stereograph image of the third Academy building from the 1880s

The fourth individual Phillips enslaved— believed to be the second enslaved person he paid taxes on in the late 1770s —was a man named Corydon. No records have been found to indicate when or where Corydon was born, and how Phillips came to enslave him. Corydon was not among the individuals Sarah Gilman inherited from her late husband. Crosbie wrote, “In his day-book, kept late in life, [Phillips] speaks frequently … of his black man, Corydon, whom he hired out at various times to the Gilmans, when he himself had no work for him.” After Phillips granted him his freedom, likely around1780 or 1781, Corydon appears to have lived as a boarder in Exeter with Hannah (Merrill) Holland, a free Black woman, and her daughter, Catherine.

Corydon, who survived Phillips bymore than two decades, is believed to have lived more than 100 years. In Corydon’s later life, Crosbie recorded, Phillips Exeter Academy and Phillips Academy paid his living expenses; Exeter paid two-thirds of the total cost and Andover the remaining one-third. Records in the Academy archives show invoices related to this financial support, with the last one dated April 1, 1818, the date of Corydon’s death.

In investigating the stories of these four enslaved individuals linked to Exeter’s early history, the committee relied not only on previously published histories of the Academy, but also on the work of Barbara Rimkunas, curator of the Exeter Historical Society, who has worked with her staff to compile numerous stories about Black residents of Exeter in the Revolutionary War period and beyond. As a commercial and political center of the region at the time, Exeter had a relatively large free Black community after the war, reaching nearly 5% of the town’s population — the largest percentage in New Hampshire at the time.

Committee resources also included research by Alexanderia Baker Haidara ’99 and a senior project by Andrew Yuan ’24, titled “Legacy of Slavery at Phillips Exeter Academy, 1770-1870.” Yuan, who completed the project as part of a research-focused history course during his upper year and served on the student branch of the committee on slavery, was inspired by similar efforts at Harvard and other institutions to begin looking into Exeter’s connections to slavery, both around the time of its founding and through its early decades.

“It’s a part of history that has not been recognized as it should have been,” Yuan said in 2024. “There was a need to really get down in the archives to know what went down during the years of Exeter’s founding as an institution, how slavery shaped it and how we as a community are reconciling with that fact.”

Just as Crosbie in 1923 acknowledged John Phillips’ ownership of enslaved people, later chroniclers of the school’s history have shed light on sometimes difficult truths about minority representation at Exeter through the years. The Committee to Study Slavery and Its Legacy at Exeter has also made efforts to further illuminate the experiences of early generations of Black students at Exeter, and to share some of their largely untold stories.

Moses Uriah Hall, who came to the Academy in 1858 and fought in the Civil War after his graduation in 1861, was previously reported (including in this magazine) to be Exeter’s first Black student. But as Julia Heskel and Davis Dyer wrote in After the Harkness Gift: A History of Phillips Exeter Academy Since 1930 (2008), “many believe that blacks were enrolled in the school as early as 1790.” They note that formal student records were lacking until the mid-19th century. And current Academy archivists say that explicit collection of student racial identification data did not begin until the late 1990s.

By the late 19th century, Exeter saw a growing number of Black students, many of whom lived in a boarding house owned by J.W. Field. They represented a small minority of the student population, but a number of these early Black Exonians became leaders on campus and went onto distinguished careers.

Although it’s difficult to cite exact figures, given the nature of student records at the time, the number of Black Exonians appears to have declined after the first decade of the 20th century and did not begin to rise until the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s.

This lack of racial diversity at Exeter reflected a much larger societal shift in the country. After the collapse of Reconstruction, many Southern states enacted legislation that restricted the freedom, safety and economic opportunity of Black citizens. As a result, beginning in 1910, millions of African Americans left the South and moved to urban centers in the North, Midwest and West, a so-called Great Migration that transformed the country.

An escape from the Jim Crow South did not mean freedom from racial prejudice.The years after World War I saw a sharp increase in racial violence, with riots breaking out in Chicago and other cities. The widespread success of D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation — screened at the White House and praised by President Woodrow Wilson — helped legitimize the resurgent Ku Klux Klan. The Birth of a Nation was also the first film shown at the Ioka Theater in downtown Exeter when it opened in November 1915. As Rimkunas reported in the Exeter News-Letter in 2015, the advertising campaign for that debut featured several costumed Klansmen riding around town on horseback.

In addition to this complicated historical context, Heskel and Dyer explore one explanation for the limited number of Black students at Exeter during the first half of the 20th century: the per-onal views of Principal Lewis Perry, wholed the Academy from 1914 to 1946. The authors drew on the words of Perry’s successor as principal, William G. Saltonstall, who weighed in on what he called the“sensitive” subject of minority representation at Exeter in his 1980 biography, Lewis Perry of Exeter: A Gentle Memoir.

“Blacks had attended Exeter long before Perry’s time and done well,” Saltonstall wrote. He then quoted from a letter Perry wrote in March 1936 to his longtime correspondent Vernon Munroe, a graduate of the class of 1892 who served as president of Exeter’s General Alumni Association. Perry had received a missive from Lucien V. Alexis, a Black alumnus of the class of 1914 who appears to have inquired about sending his son to the Academy.

“We have not had any colored boys in school for eight or ten years,” Perry wrote to Munroe in the letter, which is included in Perry’s correspondence files in the Academy archives. “Now the intimacy of the Harkness Plan, with all the boys in our own dormitories, makes things still more difficult. Frankly, I have learned enough about the school since I have been here to be very sure that a colored boy is hurt rather than helped by his entrance into Exeter.”

To support his position, as chronicled by Saltonstall and later by Heskeland Dyer, Perry cited advice that he said Booker T. Washington, president of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, had once given Al Stearns, who was principal of Andover from 1903 to 1933. Washington,Perry wrote, had told Stearns that “it was a great mistake for colored boys to come to either Exeter or Andover.”

Washington, who died in 1915, was probably the most prominent Black thinker in the country when he gave that advice. Having shot to fame with the publication of his autobiography, Up From Slavery, he wrote and spoke extensively about his belief that Black Americans should pursue training in trades like carpentry, mechanics and farming. He saw this as a crucial way for them to attain employment and economic stability without actively challenging the segregationist systems of the time. (Washington’s own son, Booker T. Washington Jr., attended Exeter for a time but left in 1907 before graduating. According to a report in the New York Times, Principal Harlan Amen denied that his departure was due to racial discrimination, stating that the younger Washington had left after being ordered to “confine himself in his dormitory certain hours for study.”)

Washington’s views had put him at odds with Black leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois, who argued against racial segregation and co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). But they struck a chord with Stearns, who — like Perry — grappled with the question of minority students at the school he led.

In Youth From Every Quarter: A Bicentennial History of Phillips Academy Andover (1979), Frederick S. Allis cited a letter Stearns wrote in 1928. In it, Stearns explained that in his early years as principal, he “fought vigorously for the colored boys in our midst and for those who sought to enter.” Later, Stearns began to doubt that position, writing that it seemed “these fellows were being harmed more than helped by the school.”

Stearns sought advice not only from Washington, but also from Hollis B. Frissell, a white Andover alumnus who served as principal of the historically Black Hampton Institute in Virginia; both men helped confirm his later perspective. From 1910 until Stearns’ tenure ended 23 years later, only one African American student graduated from Andover, according to “Our DEI History,” published on the school’s website. (In 2021, Andover introduced its Committee on Challenging Histories, the equivalent of Exeter’s committee.)

In his biography of Perry, Saltonstall wrote with warmth and admiration, calling him one of “the great headmasters who led their schools for decades and shaped much of independent secondary education in the twentieth century.” Thanks to Perry’s leadership, along with the revolutionary $5.8 million gift from the philanthropist Edward Harkness, Saltonstall wrote, Exeter embarked on “anew era of education,” transforming thes chool into what it would become today.

Yet when it came to the “question of minority representation at Exeter,” Saltonstall was no less direct. “Even within the context of [Perry’s] day this was a blind spot,” he wrote. “While it may not be fair to judge a person by the standards of a different age, Perry denied Exeter’s democratic tradition in permitting limits on the numbers of blacks and Jews in the academy. He never specifically discussed quotas of any kind, but he did suggest that limits would be advisable.

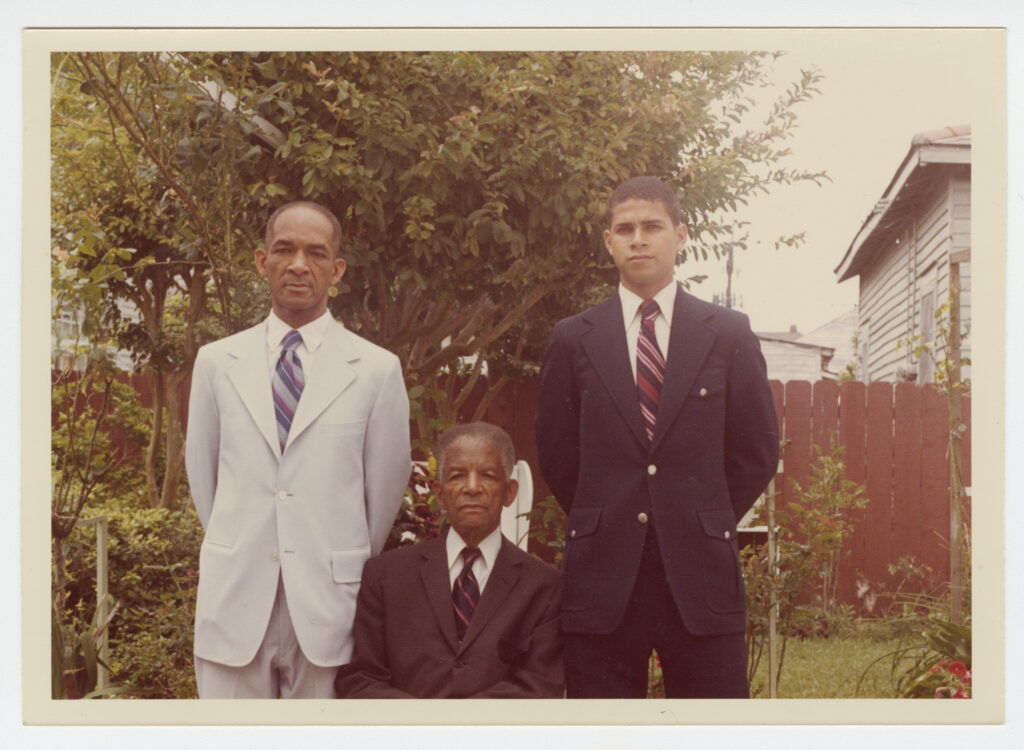

The Alexis family: Lucien V. Alexis Jr., class of 1938; Lucien V. Alexis, class of 1914; and Lucien V. Alexis III, class of 1973

This difficult history is reflected in the stories of two early Black Exonians and their sons, who sought to attend the Academy during the later years of Perry’s principalship. The first was Lucien V. Alexis, the alumnus from theAcademy’s class of 1914 whose letter to Perry prompted Perry’s correspondence with Munroe in March 1936. Then in early 1940, Eugene Clark, class of 1904, wrote to Perry regarding his son, Eugene Clark Jr. Alexis attended Exeter for one year before going to Harvard, where he graduated cum laude in 1917. When he wrote toPerry, Alexis was the founding principal of McDonogh 35 Senior High School, the first (and at the time only) public high school for Black students in Louisiana.

The Academy archives did not record Perry’s response, but Lucien V. Alexis Jr. ’38 arrived at Exeter not long after. Heskeland Dyer wrote that the younger Alexis was not permitted to live in a dormitory, so he lived with the track coach, Ralph Lovshin, who also experienced marginalization as a Roman Catholic during his early years at Exeter.

Alexis, who joined the fencing team, was the only Black student in his graduating class at Exeter. He then became the only Black student in Harvard’s class of 1942, and the first Black player on the university’s lacrosse team.

On April 16, 1941, The Exonian published a letter to the editors from Maurice Rashbaum Jr. ’41. “A week ago Saturday, Rashbaum wrote, “an event happened which I believe should be brought to the attention of every Exonian who believes… that men of all races, creeds, and colors should be treated alike.” Rashbaum referred to the Harvard lacrosse team’s trip to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. The Navy coach refused to let his team play against Harvard if Alexis was on the field. The Harvard coach stood his ground, but the university’s athletic director overruled him, and Alexis was forced to head back to Cambridge while his teammates took the field without him (Navy won, 12-0).

The incident made national news, The Harvard Gazette reported, inspiring public recriminations against both Harvard and Navy. Rashbaum joined in this outcry, arguing that “there certainly ought to be published a public apology by Navy for this ineffaceable blot on the honor of our country.” When Alexis and his team traveled to West Point, New York, to play the U.S. Military Academy a week later, Black cadets led a cheering group that welcomed them.

Alexis was later accepted to Harvard Medical School but was told he could not attend because the incoming class had no other Black student for him to room with. He returned to New Orleans, where he ran a small business college — and sent two sons to Exeter, Lucien ’73 and Llewllyn ’74. Last fall, Harvard honored him with a portrait inits Agassiz Theatre as part of the Portraiture Project of the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations.

Two years after Alexis graduated from Exeter, Perry appears to have discouraged Clark from sending his son to theAcademy. During his time there, Clark lived with other Black students in J.W.Field’s boardinghouse. After graduation, he began a distinguished career in education and retired in 1953 as president of Miner Teachers College, a historic center of Black education in Washington, D.C.

“My dear Dr. Perry,” Clark wrote. “I wish to acknowledge your kind letter of March 13, 1940, in which you very frankly explain the situation at Exeter with reference to colored students. From your description of conditions I agree with you that it would be unwise for me to send Eugene to the Academy.”

“However, as an alumnus of Exeter,” Clark continued, “I believe that it would be decidedly beneficial to the general student body at Exeter to have a few well-selected colored boys in their midst and living under normal conditions, for the boys at Exeter will ultimately be leaders in their various life activities and should have as part of their education an opportunity to develop tolerance and the democratic way of living.”

A Home for Early Black Exonians

By the 1890s, Exeter had two permanent dormitories on campus — Abbot Hall, opened in 1855, and Soule Hall, opened in 1894 — but was not yet a fully residential school. Those who did not live in the dorms rented rooms from families in and around Exeter.

Many of the Academy’s early Black students rented rooms in the same home, owned by local businessman James William Field, a member of Exeter’s class of 1890. Listed in student directories in the PEAN yearbook as “J.W. Field’s House,” the building also housed Field’s business, where he traded and sold furniture, carpets, rugs and other home goods and offered repair and packing services.

Here are a few of the Exonians who lived at 248 Water Street and some information about their lives.

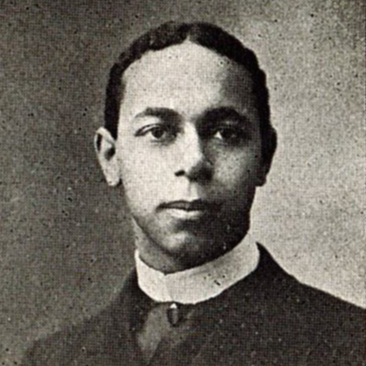

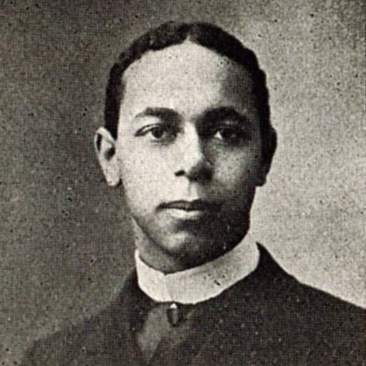

Roscoe Conkling Bruce, class of 1898

Roscoe Conkling Bruce, class of 1898

The son of a Reconstruction-era U.S. senator from Mississippi, Bruce arrived at Exeter in 1896 from Washington,D.C. In his two years at Exeter, he joined the Golden Branch debating society and was elected to The Exonian’s board of editors. He later won numerous awards for orating and debating at Harvard. After serving as academic director of the Tuskegee Institute, he worked as a principal in the District of Columbia public school system, eventually rising to assistant superintendent of the district’s African American schools.

John Tazewell Jones, class of 1900

John Tazewell Jones, class of 1900

Jones, who hailed from Old Point Comfort, Virginia, isbelieved to be Exeter’s first Black four-year varsity athlete.He excelled in football and track at the Academy beforegoing on to play football at Harvard College. At Harvard,Jones befriended Franklin D. Roosevelt, the future U.S.president, with whom he maintained a lifelong friendship. Around 1917, Jonesmoved to Brazil, where he worked for more than two decades as a businessrepresentative for U.S. firms.

Ernest Marshall, class of 1904

Ernest Marshall, class of 1904

Marshall came from Baltimore and spent three defining years at the Academy. He was highly regarded by his peers and was the first Black student to be elected as a captain of an athletic team in the Academy’s history. Marshall set records in track and field and captained the football team in 1903. He continued his education at Williams College, University of Michigan and the University of Chicago before becoming one of the first Black graduates of Northwestern Medical School. Marshall went on to find professional success as a professor, coach and physician. (For more about Marshall, read “Strength and Character” in the Fall 2023 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.

Benjamin Seldon, class of 1907

Benjamin Seldon, class of 1907

A native of New Jersey, Seldon was a member of Exeter’s football team. During his time at Exeter, he wrote to prominent sociologist and writer W.E.B. Du Bois, author of the influential essay collection The Souls of Black Folk. “I feel it is just the book that every Negro should possess, therefore I am desirous of becoming an agent for it,” Seldon wrote. This correspondence led to decades of communication and collaboration, as Seldon joined Du Bois’ pursuit of Pan-Africanism, or efforts to unify people of African descent around the world. After supporting U.S. troops as an executive secretary for the YMCA during World War I, Seldon spent time traveling in Europe and doing scholarly work at the University of Toulouse. Back in the United States, he oversaw the Negro Adult Education program of the Works Progress Administration in New Jersey in the 1930s, and later held a post in the War Finance Division of the U.S. Treasury Department.

— Panos Voulgaris

The Committee to Study Slavery and Its Legacy at Exeter continues to explore and celebrate the stories of Black alumni like Lucien Alexis Sr. and Jr. and Eugene Clark, and to fully recognize their contributions to the life and history of Exeter. As it moves into the second phase of Rawson’s 2023 charge, the committee will study and acknowledge the early generations of Black students at Exeter, and offer suggestions for further examination of their experiences and those of other historically marginalized groups.

This includes an effort — begun at the 55th anniversary celebration for the Afro-Latinx Exonian Society in2023 — to record the oral histories of students of color to include in Exeter’s institutional memory. Magee Lawhorn, co-head of the committee and director of Archives and Special Collections, is spearheading this endeavor.

“It’s really about capturing these stories for people who come after us,” Lawhorn says. “Often with history, you get photographs, you get paper, but you don’t always get the person talking about themselves, and I think that’s really important.”

Eric Logan ’92, chair of the Trustees’ Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee, says: “The idea of youth from every quarter, of Harkness — all of that is centered in having different people who can have broad discussions around a given fact basis. Being able to fill in gaps in the history of Exeter is critical to us being able to do what we do as Exonians, which is sit around a table and discuss the implications of that history, both then and now.”

A particular area of interest for the Trustees, Logan believes, is ensuring amore complete understanding of the school’s history as Exeter approaches the 250th anniversary of its founding in 2031. “It’s important for us to understand the facts, to know who we as an institution are,” Logan says. “When you look at a school with the history and legacy of Exeter, history means a lot, and it’s important that we can be as robust as possible with the history that we tell.

Members of the Committee to Study Slavery and Its Legacy at Exeter, or CSSLE: (back row) Sarah Pruitt ’95; Panos Voulgaris, instructor in physical education and varsity football coach; Kent McConnell, instructor in history; Magee Lawhorn, CSSLE co-head and head of Archives and Special Collections; Kevin Pajaro-Mariñez, assistant director of equity and inclusion; (front row) Laura Wood, director of the Class of 1945 Library; Stephanie Bramlett, CSSLE co-head and director of equity and inclusion

The committee shared some of the results of its work in a school assembly in January that aimed to raise student awareness and understanding of Exeter’s history with slavery and its legacy. In the presentation, co-heads Stephanie Bramlett and Lawhorn, and other committee members, shared some of the “untold stories” they have been exploring. They include Robin, Phillis, Dinah and Corydon, as well as Moses Hall, class of 1861, and some of the Black Exonians from the late 19th and early 20th century. They also explained the committee’s charge, in the context of similar initiatives at institutions around the country, and emphasized the importance of every Exonian’s story.

“All of us have these stories that contribute to this broader Exeter legacy and Exeter experience,” Logan says. “I think it heightens every student’s experience to understand where they lie on this continuum of the history of the Academy.”

At the end of the assembly, students and faculty gathered in Elm Street Dining Hall to enjoy some cake and “ale” (cider) in tribute to Dinah. Lawhorn researched recipes for traditional African American dishes and worked with Dining Services to create the community event.

“It was powerful to learn about these stories,” Andrew Voulgarelis ’25 says, “and to see how the community was focused on trying to learn as much as possible about this small group of people who made a big difference at the Academy, and helped make it what it is today.”

Sarah Pruitt ’95 is a staff writer for The Exeter Bulletin and a member of the Committee to Study Slavery and Its Legacy at Exeter.

This article was originally published in the spring edition of The Exeter Bulletin.