For the record: Beatlemania sweeps through Exeter

Eric Schultz brings the 'Fab Four' to life in studying the history of pop music.

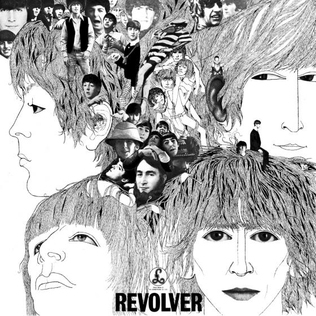

Late in the spring term, students trickling into the round room on the second floor of the Forrestal-Bowld Music Center are greeted by the sounds of side one of the Beatles’ Revolver. The iconic album, the group’s seventh full-length release, is the focus of the period’s discussion in MUS202: History of American Popular Music.

Manning the turntable, Instructor in Music Eric Schultz lifts needle from vinyl as the class reaches critical mass. This is the second of two periods devoted to the biggest act in pop music history and, more specifically, the album that cemented the change of the band’s image from boy-next-door pop stars to long-haired psychedelic pioneers.

This senior-level course explores trends in popular music in the United States and how that music reflects the cultural and political landscape in which it was made. Students are graded on “needle-drop quizzes” in which a song from a previously discussed album is played and they must name the artist, title and the year it was released. Schultz says he has been teaching some version of this class for more than two decades. The class syllabus covers a period of nearly 100 years, and he laments being able to give the Beatles only two days of conversation, noting that the University of Liverpool offers a master’s degree program on the so-called Fab Four.

Throughout the period, Schultz weaves in the historical context of Beatlemania and the immeasurable influence on not only pop music, but also the fabric of Western culture. He cues up archival footage of John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr arriving in the U.S. for the first time, landing at New York’s newly named John F. Kennedy International Airport in February 1964, greeted by thousands of frenzied fans.

“What was the major event in U.S. history that happened before this that had a real impact on people?” Schultz asks.

“J.F.K. gets assassinated,” Dhruv Nagarajan ’25 quickly responds.

“November 22, 1963, John F. Kennedy, a very popular president, assassinated in front of onlookers in Dallas,” Schultz continues. “So, then trauma, drama, bad vibes. Then Christmas. Then the new year. Then the winter. People want to be happy and the country is sick of not being happy, and then these guys show up. Look at these guys: matching haircuts, matching suits, all designed to make your dad want to hang out with them. And — it worked.”

Schultz chronicles two other important Beatles-centric cultural waypoints: the group’s first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show — estimated to have been watched live by half the country — and their chance encounter with Bob Dylan in a New York City hotel.

“We’ve talked about the drug culture of the ’60s,” Schultz says, “and this is where we really start to see that come to the fore, because Bob Dylan shows up and gives the Beatles their first marijuana joint.”

Eric Schultz deconstructs the allure of The Beatles during a meeting of his senior elective, MUS202: History of American Popular Music.

Schultz plays The Ed Sullivan Show performance as heads around the Harkness table begin to bob and feet begin to tap to the beat of “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” “This is 1964,” he says. “There are no hallucinogens involved in this. This is clean as a whisper.”

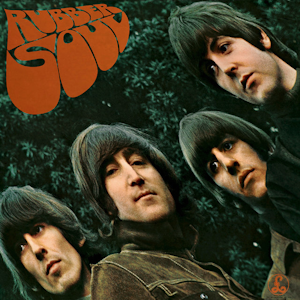

“The biggest change happens between these two albums,” Schultz says, motioning between projections of 1965’s Rubber Soul and 1966’s Revolver.

“The song ‘Yellow Submarine’ is on Revolver; you should know that yellow submarine is street slang for a type of illegal drug in London — think of the shape of a pill,” Schultz says to stunned students.

“My kindergarten class sang that song,” one replies.

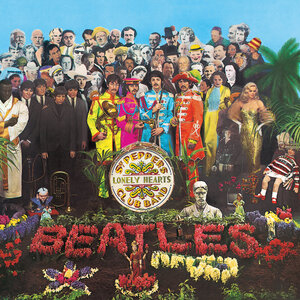

Schultz goes on to explain that the change in style wasn’t the only massive shift in the band’s output. As the complexity of their sound continued to expand with the 1967 release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the group had not played a concert for nearly a year and would play live only once more — in 1969 on the rooftop of their recording studio in London.

“The Beatles spent eight hours recording their first album. They spent 900 hours in the studio for this one,” Schultz says, holding up a copy of Sgt. Pepper’s. “This is them saying: ‘We’re not doing live music anymore. We’re only going to make albums in the studio. And that way, we don’t have to worry about whether or not we can play it live.’”

With the final minutes of class dwindling, Schultz races through the band’s final albums and slow unraveling, again lamenting, “There’s never enough time to talk about the Beatles.”

This story was originally published in the Summer 2025 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.