Faculty

Faculty

Passions

With wide-ranging interests and experiences, each Academy faculty member brings a unique set of talents and insight to the classroom. This personal lens is a superpower, adding nuance and passion to the curriculum, often leading to exciting new courses that both reflect the adaptability of Exeter’s course offerings and the instructor’s academic excellence and personality.

Meet five of the 247 faculty members who bring their full selves to the table —and the classes they have inspired.

Instructor in Science Summer Morrill ’11 in her classroom.

Genetics of Cancer

Summer Morrill ’11

Instructor in Science

Summer Morrill ’11 fell in love with studying biology and genetics while a student at Exeter. But it was her family history of breast cancer that inspired her to study genetics at Tufts, then in graduate school at MIT. “I’ve had the experience of meeting with a genetic counselor to try to understand what’s going on,” she says. “The things I’ve researched and discovered may not make a conscious impact during my lifetime, but there’s something empowering about studying it.”

While Morrill considered becoming a genetic counselor, she decided she was more suited to the academic side of science, especially after gaining teaching experience during graduate school. She teaches a course in cancer biology, BIO586: Molecular Genetics. She proposed it as a special course based on several students’ initial interest, but when she offered it, 25 students signed up. “So many students approached me asking for this course,” Morrill says.

Why so much interest? “Cancer research is a huge field with really interesting biology happening now,” she says. “Also, students personally are interested in learning more about cancer research. The disease touches a lot of families, friends and, at this point in their lives, they probably know someone who has cancer.”

Students in Morrill’s course read current research on cancer genetics and do lab work focused on learning techniques of DNA isolation, analysis and manipulation. Morrill also organizes a panel of biologists — representing organizations including Boston Children’s Hospital, the National Institutes of Health, and Merck — to meet students and answer questions. “The questions the students ask are what researchers are currently asking in the field, which is amazing,” she says.

Morrill is creating further iterations of the course, giving students more opportunities to tie together different elements they have learned, such as thinking how gene mutation works and what the human body can and can’t do in response. “If they understand a problem at multiple levels, that’s going to benefit their problem-solving ability when it comes to thinking about human disease and how we’re treating patients,” she says.

“A course like this can teach students that science is more than just memorizing a set of facts. It’s about being comfortable with the unknown and asking the right questions to further your understanding of the field. I think there’s huge value in that for students — even one who doesn’t want to go into cancer biology — to have the experience of connecting pieces together and doing research of your own to figure out what’s going on in such a new field.”

Instructor in English Jason BreMiller teaching in the Academy woodlands.

Wild About Nature

Jason BreMiller

Instructor in English

Jason BreMiller is as passionate about the outdoors as he is about literature. Last winter, to illustrate concepts discussed in his ENG420 course, he led students on a walk through the woods to build a fire, cook, then taste a deer heart from an animal he had humanely harvested.

At different points in his teaching career — before and after arriving at Exeter in 2012 — BreMiller has guided students through ice caves in Iceland, up Tanzania’s Mount Kilimanjaro and through the Serengeti because he believes place-based education helps students learn. “I’ve tried in my pedagogy to set a high bar of traditional academic rigor but explore different possibilities for its delivery,” BreMiller says.

His ENG572: Literature and the Land course is centered around weekly field trips — hikes through forests, visits to local orchards, explorations of the New Hampshire Seacoast — connected to the stories students read and discuss in class. “Literature and the Land is really built around deepening students’ awareness of and connection to place, and relying on the body of literature that’s conducive to that,” BreMiller says. “It’s perfect for seniors who are poised to reflect about transition. We visit places designed to prompt them to think about what it means to have a relationship to place that’s both good for human and biological communities.”

BreMiller spent much of his childhood exploring the outdoors, observing animals and learning to bow hunt with the help of his father, a wildlife enthusiast who often brought animals into the house. “My childhood was unusual in the sense that you’d go get ice cream and all these bird specimens would just spill out of the freezer,” he says. “I also remember we glued a turtle back together that had cracked its shell on the road. I grew up with a deep affinity for natural spaces and a comfort with being outdoors.”

After pursuing studies in environmental humanities in college and graduate school, BreMiller gravitated to mountaineering and backpacking, completing a NOLS outdoor educator mountaineering course and becoming a field instructor. “These pieces fit in my teaching career, where I saw the value of being outdoors with students and observing firsthand the magic that is both intellectual and deeply internal by teaching in wild places,” he says.

BreMiller is the founder and director of Exeter’s Environmental Literature Institute, a weeklong conference for teachers, and established INT519: Green Umbrella Learning Lab, an integrated studies course which gives students an opportunity to dig into sustainability projects on and off campus. Among its successes were the introduction of RedBikes, a campus bike share program, and an initiative to raise the awareness of local drinking water quality. “The kids are developing the skills to execute high stakes, complex projects with real outcomes for the community, which in mymind is the logical extension of Harkness pedagogy,” he says.

One idea BreMiller is contemplating is a field-based, interdisciplinary course on the philosophy and ethics of hunting. It invites many complex questions but, most important to BreMiller, it takes those conversations outdoors.

Drawing on Experience

Tara Lewis

Instructor in Art and the Clowes Teaching Chair in Art

Tara Lewis believes all students are artists, whether they have been sketching for years or have not picked up a paint brush since elementary school. A painter who often shows her work in New York City galleries, Lewis has taught painting, drawing, 3D design, printmaking and photography at all levels around a Harkness table in the Frederick R. Mayer Art Center. She draws on her dual passions in contemporary art (especially pop art) and portraiture to inspire students. “I love to weave the contemporary art world into my course content in a very impactful and tangible way,” she says.

Lewis regularly invites working artists to meet and work alongside students. American artist William Wegman visited campus to discuss the whimsical compositions he creates featuring dogs — mostly his Weimaraners in various costumes. Casey Cadwallader ’97, creative director for the fashion brand Mugler, made a guest appearance. Portrait artist Nicolas Coleman ’16 set up a mini studio in Lewis’s classroom and painted in tandem with students.

Some of these visits lead to further inspiration and connection. After hosting painter Will Cotton, several of Lewis’s former students went on to become studio assistants and interns. “The students gain technical inspiration that enhances their own studio practice,” Lewis says. “But it’s great when alumni come into the art classroom because I have them talk about what they were creating in high school or simply what they were like then. I want the students to realize that artists were actually 16 once too.”

Lewis enthusiastically shares personal experiences and insight in her ART408: Advanced Projects: Painting Portraits course. “My own studio practice is rooted in portraiture, and I love collaborations due to the unexpected and rewarding outcomes that can occur,” Lewis says. “I can’t help but let who I am spill into the classroom!” Early in the course, Lewis introduces possible portrait subjects through music videos, photography, literature, other artists’ work and more. Students develop a concept for the portrait they want to create, find a model, then create a portrait throughout the term.

Last spring in New York, a chance collaboration with model Brooke Shields led to an exhibition of Lewis’s pop culture-infused portraits of her and her daughters. She uses that example to motivate students.

“I love to share tips about the portrait process,” Lewis says. “I tell students to be present in the moment — know your concept, idea and subject you wish to portray. Make a documentary on canvas!”

Clara Peng ’24 and Instructor in History Troy Samuels explore artifacts.

Serving Up History

Troy Samuels

Instructor in History

Troy Samuels is known for making learning history a whole-body experience. Students in his HIS568: History Through Food course, for example, examine the relationship between cultures and food around the world through readings, then prepare a meal based on the concepts they’re discussing. “We have Harkness in the classroom, then we have Harkness in the kitchen,” Samuels says.

The course was inspired by a student project in one of Samuels’ 300-level European history classes. “A student from Venezuela researched the creation of Venezuelan food at the intersection of European and South American culture, which I thought was really cool,” Samuels says. “There are so many rich intersections between how food and the everyday lives of people interact with history.”

Based on themes provided by Samuels, each week two student “chefs” create a menu around a recipe they select and join Samuels in the basement of the Elizabeth Phillips Academy Center to cook a three-course meal. Exploring various themes such as food and economy, or food and empire, students prepare a variety of dishes — for example, lamb stew using ingredients adapted from a Babylonian cuneiform tablet or lobster rolls after discussing food and social status. They’re urged to taste everything (barring dietary restrictions or allergies). And, under Samuels’s supervision, they’re learning real cooking skills. “One of the broader trends we explore is how interconnected our world is,” he says. The class becomes a community event, especially on cooking days. “People invite their friends to help cook, to try things, to understand what they’re doing, and it becomes a little party,” he says.

In addition to cooking, Samuels encourages his students to engage with the active work of historians: digging. He is an archaeologist and a specialist in the material culture of understudied people in the ancient world. As a senior staff member on the Gabii Project, an international archaeological initiative in Italy, he has offered Exeter students the opportunity to work with him at the site outside Rome for the past two summers. “They’re the only high school students there, and they really distinguish themselves because they’re so insightful and energized,” Samuels says. “It’s also a great opportunity for them to experience a different side of being a historian.”

Samuels jokes that, “with a name like Troy, I was doomed to be an ancient historian,” but his hope is for students to find joy in learning history. “It’s about finding engagement with the past and that search for complexity and understanding and how that can be really rewarding,” he says.

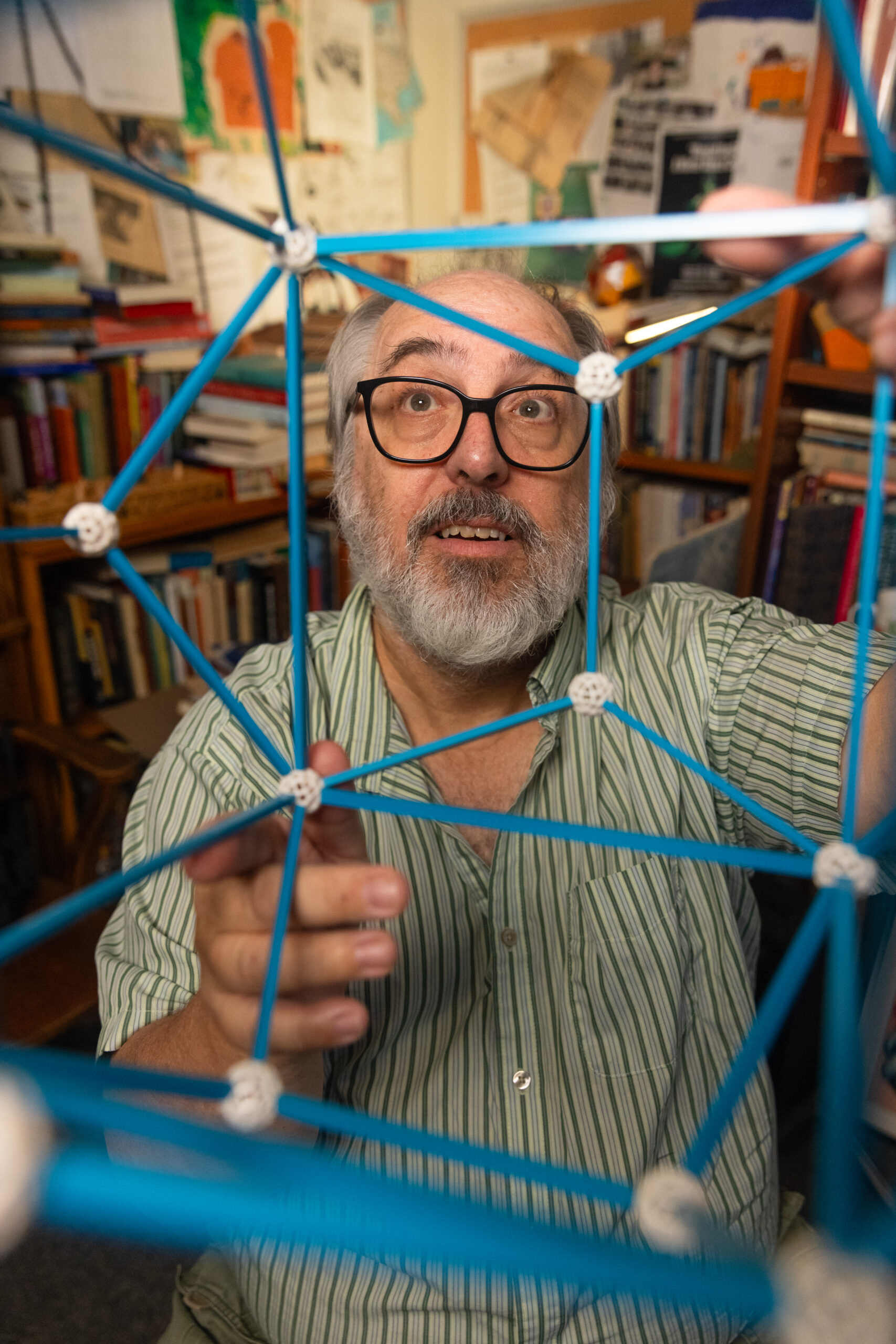

Calculated Fun

Jeff Ibbotson

Instructor in Mathematics

Learning advanced mathematics concepts isn’t necessarily fun and games — except in Instructor Jeff Ibbotson’s MAT690: Selected Topics in Mathematics course, where games are the point. In it, students explore how game theory — the study of strategic interactions whose outcome for each participant depends on choices of all involved — is an effective way to apply mathematical calculations to strategic thinking.

“Game theory allows students to see applications of mathematics in a different way because the concept is based on the idea of agents playing a game against one another or as part of a group,” Ibbotson says. “Games like the Prisoner’s Dilemma have aspects of conflict and cooperation, and can apply to situations in politics and economics.” Two of his students applied the game theory model of cooperation to show how hermit crabs trade shells, writing and illustrating a picture book to explain their findings.

Ibbotson aspires to teach mathematics beyond theorems and formulas, and attract a broad range of students, some who enjoy math and others who feel they should give math another try. Maybe because Ibbotson didn’t always know mathematics would be his route to happiness.

“When I was in college, I was a physics major and I wound up completing a physics program,” he says. “I took English classes, but eventually the style of arguments got to me. I was like I want something where there’s a provable answer. Not that I didn’t enjoy arguing, I do. … but it was when I was in real analysis that I fell in love with the mathematics of infinity.”

Drawing on his vast interests in art, religion and history, he uses spherical paintings on a globe to illustrate six-point perspective or passes around a graspable dodecahedron to help students visualize complex ideas. In another course he developed,

MAT40H: History of Mathematics, students study numbering systems from ancient Egypt, Babylon, China, India and other non-Western cultures — and have an opportunity to build their own. “They invent their own symbols and the stories behind the symbols,” Ibbotson says.

Ibbotson has been able to share his fondness for physics in an integrated studies course about the intersection of mathematics and sound. Using content based on his research into distribution theory and partial differential equations, students use trigonometric functions like sine and cosine to model complex sound waves (which correspond to musical concepts like pitch and volume). An avid Marvel and DC comic book fan, Ibbotson hasn’t integrated comics into his math courses, but he plans to.

In everything he teaches, Ibbotson strives to impart that learning mathematics is an effective way to learn to think, especially around the Harkness table. “That pedagogy feels right to me,” he says. “We want students engaged as soon as possible in doing mathematics. We have all sorts of problems that can go in various directions and sometimes the students find original ways to solve them. We celebrate that.”

Debbie Kane is a longtime contributor to The Exeter Bulletin. Her work has also appeared in AIA NH Forum, New Hampshire Home and New Hampshire Magazine.

This article was originally published in the Fall 2024 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.