We think of a library, even now in the digital age, as being most of all about books. The Class of 1945 Library certainly has many of those. Since its opening in 1971 with 80,000 volumes, the collection has grown to 140,000, and it continues to expand through databases that give access to library holdings throughout the world. But it is about so much more. As these letters make clear, our library is a place of stored memories and shared experiences, a place of community connection across generations, a place where the holdings are just the beginning of the story.

More than 50 years ago, the Program Statement, written by the library committee that recommended Louis Kahn as architect, suggested the new library be about what takes place inside, calling for a building that was “no longer a mere depository for books and periodicals, the modern library becomes … a quiet retreat for study, reading, and reflection; the intellectual center of the community.” Surely, over its first five decades, the Academy Library has fulfilled that directive, and beyond. Not only a quiet place for reflection and study, the library has touched the lives of so many — students and faculty, of course, but also alumni, parents, staff and friends outside the Academy community. Its impact demonstrates that the wisdom of author Wendy Lesser’s comment on its architecture, in her biography of Kahn, also applies to what’s happened on the inside of our library, that “There is always something new to be discovered here: that is the main thing the library seems to be saying.”

“There is always something new to be discovered here: that is the main thing the library seems to be saying.”

Wendy Lesser, author “You Say to Brick: The Life of Louis Kahn”

In what is surely a most important moment in the library’s history, both symbolically and practically, Librarian Jacquelyn Thomas ’45, ’62, ’69 (Hon.); P’78, P’79, P’81 decided to place a Harkness table in the middle of Rockefeller Hall, thereby acknowledging that the icon of Exeter’s pedagogy should have pride of place in the library, that it, too, should be recognized as a classroom, albeit a very large and glorious one. Classes have met there ever since, undisturbed and focused, as patrons walked by observing at the table what Exeter is all about.

Harkness tables and Harkness classes in the library have proliferated, so that the dozens of classes held there annually in the early years now number in the hundreds. Prominent among them were those in Junior Studies, an interdisciplinary course for preps begun when the new curriculum was adopted in the mid-1980s. At the end of fall term, all preps and their instructors gathered in Rockefeller Hall for their first Exeter “graduation,” complete with officiants garbed in academic robes, proclamations read and time capsules stored. Four years later, those preps, now seniors, opened those capsules to revisit the artifacts inside from their first term at the Academy.

As preps matured as scholars, the extent of their use of library resources grew, culminating for many in the History Department’s term paper, when 300-plus uppers and a few seniors descended on the library each spring. A collection of sources as extensive as ours, not to mention online databases, allowed students to explore most any topic they could conjure up, such as Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago as a Cold War weapon through recently released CIA documents; or the 1918 influenza pandemic in New York through the official papers of the city’s Department of Health; or Henry Kissinger’s role in the opening of China through the foreign relations papers in our stacks.

Sometimes this research produced unexpected discover-ies. In 2014, upper Dana Tung included in her bibliography Richard Nixon’s Six Crises, in which she found a “dickey slip” issued to T.G. Katzman on Nov. 14, 1972, 42 years earlier, for missing A.A. Polychronis’ science class. On the opposite side was a note, written by Nathan Radford ’91, stating “… T.G. got this Dicky even before I was born and who knows maybe I’m writing this to someone who isn’t even born yet. … Don’t get stressed. … Stop to smell the roses. Listen to the Grateful Dead. Jerry saves. … Good luck.” Here the library brought together, through Dana’s discovery, three Exonians, generations apart. Dana added her own note to the book, along with Nathan’s, awaiting discovery by a future Exonian.

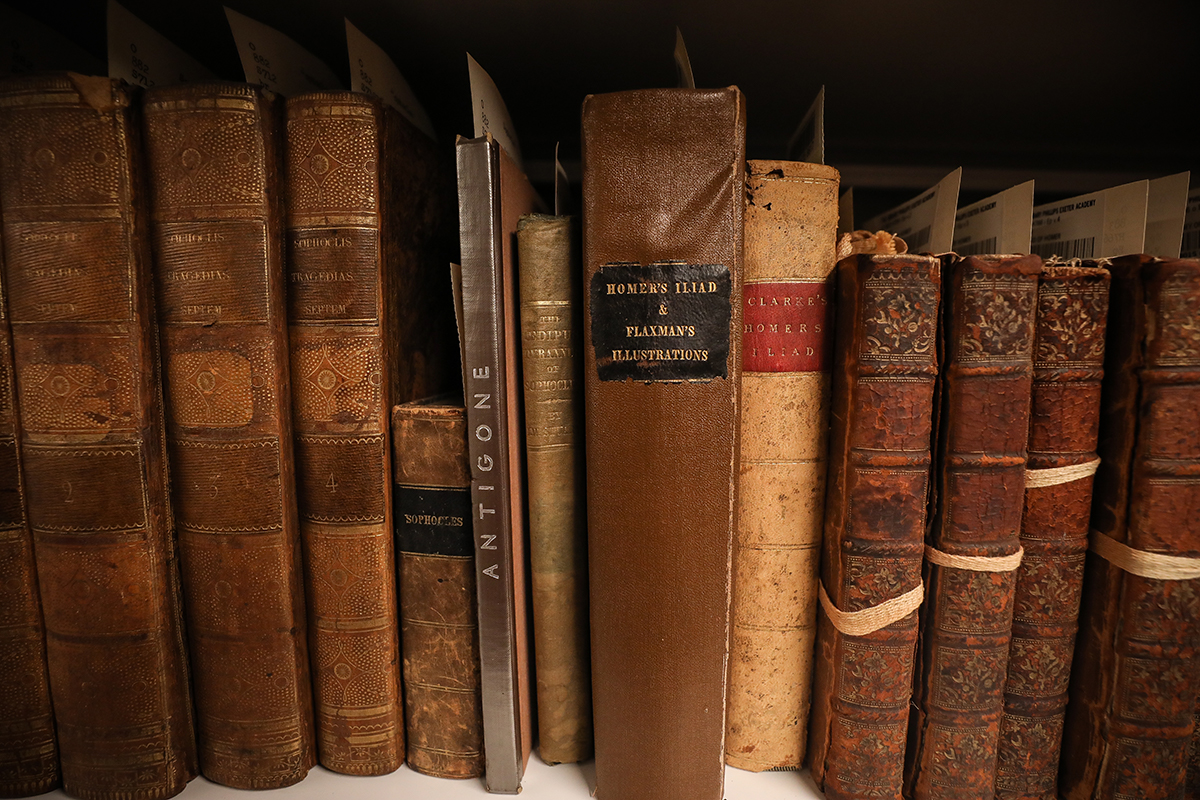

English classes have long made use of the library’s rare copy of Shakespeare’s Second Folio from 1632 and, more recently, his Fourth Folio, students delicately leafing through with white gloves to marvel at these treasures. Homage to The Bard has taken more robust forms, including the 450th birthday celebration with students, faculty and alums standing on the Harkness table in Rockefeller Hall performing scenes from his plays. That was just part of a spectacular that also featured poetry on a Caliban theme written by English Instructor Todd Hearon and set to music by Greg Brown ’93. The students of English Instructor Becky Moore’s Children’s Literature course used the library’s design itself for a class in which they partnered with children from the Harris Family Children’s Center. Having identified the countless geometric shapes one sees simply by looking around and up in Rockefeller Hall, Becky’s students helped the youngsters find and name them, increasing their mathematical vocabulary.

English classes have long made use of the library’s rare copy of Shakespeare’s Second Folio from 1632 and, more recently, his Fourth Folio, students delicately leafing through with white gloves to marvel at these treasures. Homage to The Bard has taken more robust forms, including the 450th birthday celebration with students, faculty and alums standing on the Harkness table in Rockefeller Hall performing scenes from his plays. That was just part of a spectacular that also featured poetry on a Caliban theme written by English Instructor Todd Hearon and set to music by Greg Brown ’93. The students of English Instructor Becky Moore’s Children’s Literature course used the library’s design itself for a class in which they partnered with children from the Harris Family Children’s Center. Having identified the countless geometric shapes one sees simply by looking around and up in Rockefeller Hall, Becky’s students helped the youngsters find and name them, increasing their mathematical vocabulary.

The Art Department also made constructive use of the design features of Rockefeller Hall. One assignment for an architecture course required students to build a parachute device that would cradle an egg. After the parachute was dropped from the upper levels, it would hopefully land the egg safely, unbroken, on the floor. Naturally, the final day of this project, when students launched their parachutes, became a spectator sport as eager onlookers watched the result: safe landing or … splat. That event has since been moved outside the building, for obvious reasons. And the Modern Language Department for a time oversaw a browsing area and video collection for eager linguists. These examples help explain how the library has secured its place as one of the Academy’s most exciting classrooms.

doubt logged many hours rummaging through the collection. Other Exeter faculty have found the library to be a welcoming host for presentations of their published work, as when Dolores Kendrick read from her Women of Plums: Poems in the Voices of Slave Women, just one of the many Academy authors to find there an appreciative audience.

doubt logged many hours rummaging through the collection. Other Exeter faculty have found the library to be a welcoming host for presentations of their published work, as when Dolores Kendrick read from her Women of Plums: Poems in the Voices of Slave Women, just one of the many Academy authors to find there an appreciative audience.

extensive collection of original manuscripts is Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny on the Bounty. While many of the Special Collections are housed in the archives for safekeeping, the Bates Mountaineering Collection of 500-plus titles is housed in its own room open to the public. When the Academy received the 300-plus films of the Ottaway/Adams Silent Film Collection, a showing of “The Phantom of the Opera” marked the event, signifying the collection’s availability for entertainment as well as research. In 1987, the library published a pamphlet, Rarities of Our Time, which details all of the impressive holdings in the Special Collections, yet another part of the library’s inventory of discoveries to be found.

extensive collection of original manuscripts is Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny on the Bounty. While many of the Special Collections are housed in the archives for safekeeping, the Bates Mountaineering Collection of 500-plus titles is housed in its own room open to the public. When the Academy received the 300-plus films of the Ottaway/Adams Silent Film Collection, a showing of “The Phantom of the Opera” marked the event, signifying the collection’s availability for entertainment as well as research. In 1987, the library published a pamphlet, Rarities of Our Time, which details all of the impressive holdings in the Special Collections, yet another part of the library’s inventory of discoveries to be found. they weren’t similarly successful one December night in ferreting out persons hidden away. Then-Librarian Ted Bedford recounted how students snuck out of hiding after the 9 p.m. closing to decorate the giant Christmas tree in Rockefeller Hall, so that surprised librarians found the next morning an evergreen, previously decorated only with lights, now adorned with all manner of cranberry and popcorn garlands and handmade ornaments. Given the tree’s height of 30 feet, that was, as Bedford reported, “no easy task, even for elves with high SAT scores.” Other uninvited guests were not so constructive. Take the Andover students who released 57 mice, painted blue, on floor 3M, requiring their capture by librarians, on their hands and knees. Jackie Thomas patrolled the next day with her cat, McCavity, to ensure the job was complete.

they weren’t similarly successful one December night in ferreting out persons hidden away. Then-Librarian Ted Bedford recounted how students snuck out of hiding after the 9 p.m. closing to decorate the giant Christmas tree in Rockefeller Hall, so that surprised librarians found the next morning an evergreen, previously decorated only with lights, now adorned with all manner of cranberry and popcorn garlands and handmade ornaments. Given the tree’s height of 30 feet, that was, as Bedford reported, “no easy task, even for elves with high SAT scores.” Other uninvited guests were not so constructive. Take the Andover students who released 57 mice, painted blue, on floor 3M, requiring their capture by librarians, on their hands and knees. Jackie Thomas patrolled the next day with her cat, McCavity, to ensure the job was complete.

Lacasse feels the building’s impact on a more immediate level, too, having studied it since he was in design school. “It falls into a very small category of projects that, having studied it and finally getting to see it in person, exceeds expectations,” says Lacasse. “Oftentimes when you’ve built up an admiration of a building through books and magazines or other formats, when you actually visit, them they sort of fall flat.” This was the opposite, he says. “I think it’s the emotional experience that you get from the light and the warmth and the inviting nature of the finishes, the sensory experience. This was, ‘Wow, this is better than I thought!’”

Lacasse feels the building’s impact on a more immediate level, too, having studied it since he was in design school. “It falls into a very small category of projects that, having studied it and finally getting to see it in person, exceeds expectations,” says Lacasse. “Oftentimes when you’ve built up an admiration of a building through books and magazines or other formats, when you actually visit, them they sort of fall flat.” This was the opposite, he says. “I think it’s the emotional experience that you get from the light and the warmth and the inviting nature of the finishes, the sensory experience. This was, ‘Wow, this is better than I thought!’”