James E. Coleman Jr. ’66; P ’16

Growing up in segregated Charlotte, North Carolina, James Coleman ’66 witnessed injustice and discrimination — and was moved to fight it. During his senior year in high school, Coleman worked for local civil rights lawyer Julius LeVonne Chambers, who successfully litigated a case forcing the Charlotte public schools to desegregate. “His office and home were bombed,” Coleman says. “To me, that meant he was threatening the status quo, and that being a lawyer was a way to do that.”

During his senior year in high school, Coleman worked for local civil rights lawyer Julius LeVonne Chambers, who successfully litigated a case forcing the Charlotte public schools to desegregate. “His office and home were bombed,” Coleman says. “To me, that meant he was threatening the status quo, and that being a lawyer was a way to do that.”

Coleman has carried the lessons learned that year through his long career as an attorney, both in private practice and government service. As a professor at Duke University School of Law and director of the school’s Wrongful Convictions Clinic, he helps students champion the wrongly accused. “Trying to remedy a miscarriage of justice is one of the highest callings we have as lawyers,” he says.

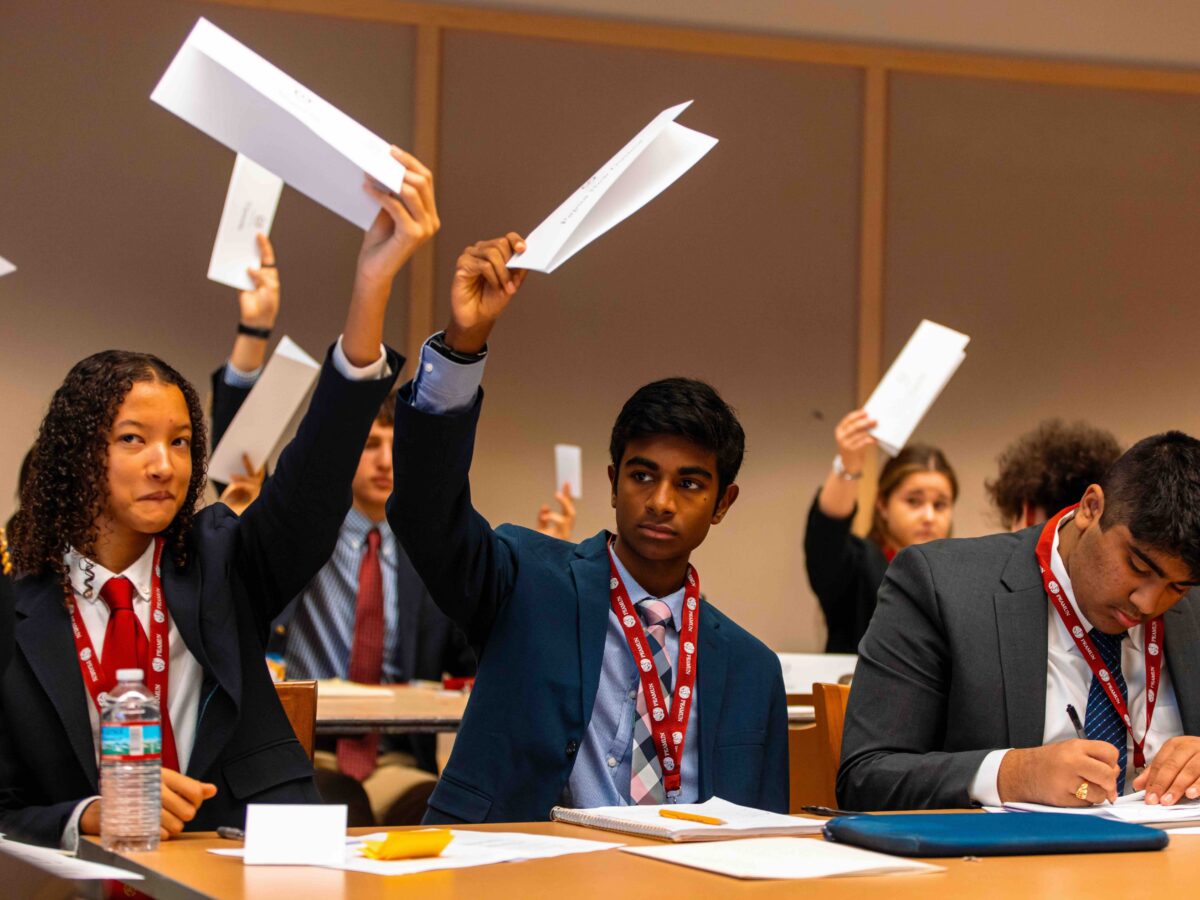

The summer before interning with Chambers, Coleman attended Exeter for a five-week academic enrichment program. It was a summer of firsts: his first experience living away from home; his first classes with white students and teachers; his first discussions around a Harkness table. Drawn by the educational opportunities Exeter afforded, he returned for a postgraduate year in 1965.

In an essay entitled “Living in the Shadow of American Racism,” published in 2022 in Duke’s Law and Contemporary Problems journal, Coleman recalls writing English essays at Exeter about growing up in a segregated country. A classmate, the grandson of a U.S. president, wrote about traveling with his grandfather. “Such diversity was not the purpose of my admission to Exeter,” he wrote, “but it was a natural consequence … facilitated by the Harkness method, where we were all equal around the table.

After graduating from Harvard University and Columbia Law School, Coleman worked in various positions in the public sector, including deputy general counsel for the U.S. Department of Education. He later joined Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering, a law firm specializing in federal court and administrative legislation. Active in the firm’s pro bono program, he advised civil rights organizations and represented clients in discrimination cases.

In another case with intense media coverage, Coleman chaired an internal committee investigating accusations of rape against several members of the Duke University men’s lacrosse team in 2006. Again, he focused on the need to not rush to judgment. “We wanted to make sure the facts were accurate,” Coleman says. “It’s easy to convict an innocent person, and, in a sexual assault case, it’s particularly hard to prove after a conviction that the perpetrator is innocent.” Charges against the team members were ultimately dropped because of inconsistencies in the accuser’s testimony and ethical violations by the district attorney.

In another case with intense media coverage, Coleman chaired an internal committee investigating accusations of rape against several members of the Duke University men’s lacrosse team in 2006. Again, he focused on the need to not rush to judgment. “We wanted to make sure the facts were accurate,” Coleman says. “It’s easy to convict an innocent person, and, in a sexual assault case, it’s particularly hard to prove after a conviction that the perpetrator is innocent.” Charges against the team members were ultimately dropped because of inconsistencies in the accuser’s testimony and ethical violations by the district attorney. “I was in some tiny museum, looking at evidence of tortoises that had gone extinct,” Dunfey recalls of her time in the Galapagos. “When you’re in a place like that, you’re so aware of biology, animal evolution, this whole notion of extinction. I thought, [the story of the bison] is such an American tale of de-extinction. It’s about our relationship to the natural world, which we ignore at our peril… but it’s also about our relationship to each other, as humans.” Drawn to the idea of sharing one more uniquely American story with millions of public television viewers, Dunfey put her retirement on hold, and signed on to produce the film.

“I was in some tiny museum, looking at evidence of tortoises that had gone extinct,” Dunfey recalls of her time in the Galapagos. “When you’re in a place like that, you’re so aware of biology, animal evolution, this whole notion of extinction. I thought, [the story of the bison] is such an American tale of de-extinction. It’s about our relationship to the natural world, which we ignore at our peril… but it’s also about our relationship to each other, as humans.” Drawn to the idea of sharing one more uniquely American story with millions of public television viewers, Dunfey put her retirement on hold, and signed on to produce the film.

Once she returned stateside, Steffensen pursued a second master’s degree in divinity and became ordained a priest in 2012. As assistant to the rector at Grace Episcopal Church in Alexandria, Virginia, she ministered to the church’s Latino congregation, La Gracia, helping them develop their sense of leadership and mission in the parish and wider community.

Once she returned stateside, Steffensen pursued a second master’s degree in divinity and became ordained a priest in 2012. As assistant to the rector at Grace Episcopal Church in Alexandria, Virginia, she ministered to the church’s Latino congregation, La Gracia, helping them develop their sense of leadership and mission in the parish and wider community.