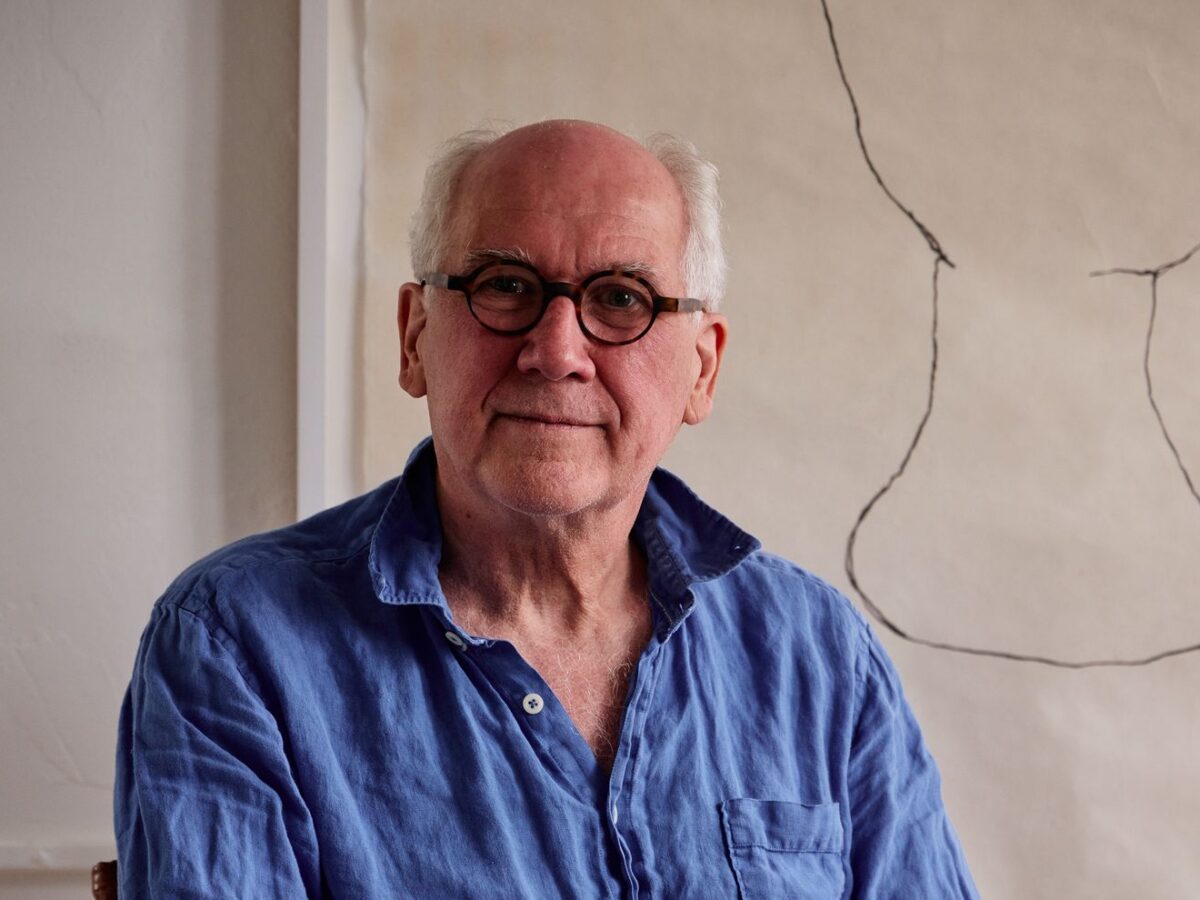

Nate McBride ’70: Building by listening

Architect 'Nate' Donald Craig McBride ’70 shares the secrets to his success.

When he was a child, Nate McBride ’70 asked his father, a doctor, what he did all day. “I listen,” his dad replied. “If I listen long enough and well enough, the patient will self-diagnose.”

As an architect, McBride doesn’t treat patients, but he likewise finds that he cannot do his job without careful listening. It’s a skill that comes naturally to someone who has always been curious and, in his own words, “compelled to understand more about human nature.”

During his two years at Exeter, McBride read Erich Fromm and Malcolm X in his (decidedly non-theocentric) religion class. As a Stanford undergraduate, he studied cultural anthropology, psychology, poetry and literature — “anything to help me understand what humankind is about,” he says.

At the same time, he was fascinated by the spaces and structures surrounding people. Exeter’s dorms prompted an epiphany: “My relationships with people in Hoyt — which were ‘What floor do you live on?’ — were entirely different from those I forged when I was in a cluster in Main Street B,” he says. Different spaces, he realized, had the power to “engender profoundly different human experiences.”

He ultimately earned a Master of Architecture degree at Yale School of Architecture and founded McBride Architects in 1983.

Exterior and interior views of the multi-cabin compound Nate McBride ’70 designed overlooking Penobscot Bay in Maine.

Now, 40-plus years later, McBride presides over an eclectic oeuvre. He has constructed snug seaside cottages and renovated palatial midtown Manhattan town houses. He has built art galleries and institutional spaces. He has designed houses of worship. His clients include homeowners, business moguls, artists, colleges and Tibetan monks, among others. Not bad for a guy who says half-jokingly that he hopes his epitaph will read, “He Almost Crossed Everything Off His List.”

Differences notwithstanding, every project he undertakes relies on the same figurative foundation. “I have to be humble enough to listen,” he says. “To do a project, I need to understand who the person is that I’m sitting with and talking to, what their larger context is. If I’m going to make art and also make responsible buildings, I need to have a deep understanding of somebody other than myself.”

Gently but relentlessly, he mines his clients for insights: What do they do when they get up in the morning? How do they spend their days? What are their habits or rituals? What is their connection to or history with the physical site? How do they plan to use the space? And the underlying critical question, “What is most important to you?”

“What we’re doing is a process of self-discovery, then building something that’s reflective of that,” McBride says. He is simply the self-described “trip guide,” asking the right questions, challenging preconceptions and offering suggestions (“sometimes softly and sometimes adamantly”) with the goal of creating a structure that reflects the client’s deepest self. He has discovered that uncomfortable budget conversations are a blessing, because “you really get to essentials. You can’t have all that, so what’s really important?”

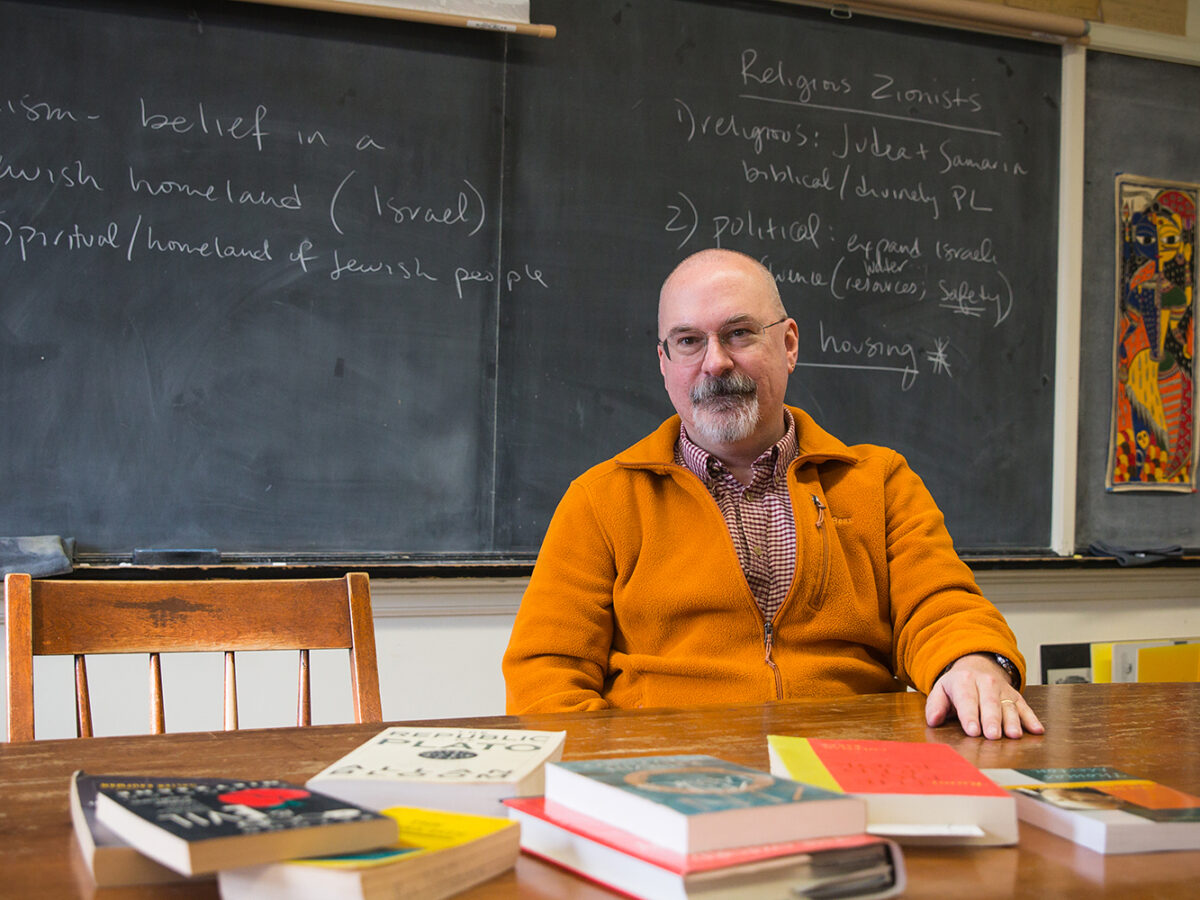

When a friend offered him a pro bono job designing community, spiritual and educational buildings for Tibetans in Nepal and India, McBride, a native Iowan, knew he would have to educate himself. Harking back to the Harkness table, he turned the initial client meetings into lessons.

“You need to teach us first what Buddhism means,” he said. Visiting Tibetan monks in red robes (“Such pageantry!” McBride says) flowed into his Tribeca office, where they ate plain lettuce and taught McBride’s team about Buddhism, about the diaspora that landed Tibetans in Nepal and India, and about the importance of helping the next generations of Tibetans “understand their traditions, history, who they are and who they could be in a new world.”

As a result of such intensive cross-cultural lessons, McBride was able to design a Buddhist monastery in Pokhara, Nepal, and a school and community center in Mundgod, India, for which the Dalai Lama laid the cornerstone. The sites are quite different: The colorful Nepalese monastery manages to be both imposing and festive, while the low Indian buildings exude serenity, rising organically from the surrounding green. Both feel consistent with the equanimity that characterizes Tibetan Buddhism.

In obvious ways, these projects were anomalous for McBride. But at a deeper level, he says, they were simply “an extreme example of what should happen on every project.” Whether a house, a library or a spiritual center, he adds: “There’s an element of ritual to the day. Some of us call it habit, but you take it to another spiritual level and all of a sudden, it’s a religious set of traditions. Understanding and building the experience of the spaces around those rituals is essentially no different than what I do with a client at home.”

Depending on the project, McBride might need to consider yet another partner: the land itself. “I need not just a humility about whom I’m building for, but a humility about the place in which I’m building,” he says. “To do that sensitively and successfully requires listening to the land. It sounds very woo-woo. (I am a ’60s child, and I did do time in California!) But to feel the wind, and see how the sun grazes the land in the morning and evening, really informs how the building, as Louis Kahn would say, ‘wants to be.’ ”

Sometimes, he’ll have one idea but the land will have another. A few years ago, clients hired him to build a house on a particularly dramatic site: a tumble of undulating green, ribbed with piney ridges, culminating in a spectacular precipice overlooking Penobscot Bay in Maine. Awed by the immense grandeur, McBride could not figure out a way to fulfill the clients’ request. “To build the [desired] square footage in a singular structure would have been in competition with what is astoundingly beautiful on its own, which is the landscape,” he says. “How to be reverent and meld with the landscape, instead of trying to command the landscape?”

McBride designed this Buddhist monastery in Pokrah, Nepal.

As he explored the area, an unexpected mental image took shape. Instead of one massive structure, he envisioned a small compound of three wooden cabins, each with a unique view. “The cabins began to find their place in the land,” he says. “The land was informing the position of those places.” These days, McBride lives in Connecticut with his wife, an interior designer and frequent collaborator, in an 18th-century wooden house: a cozy hobbit home, with low beamed ceilings and cheerful floral wallpaper, renovated and decorated by the couple. He’s considering collecting his thoughts in a book, “not because they’re necessarily original,” he says, but because it would “in a way be more meaningful to me than putting together the oeuvre because these thoughts are what’s led to the life’s work.”

And what is most important to him? “Dreaming, imagining, seeing and understanding.” Also, an outdoor shower. “It will change your experience of yourself and your world,” he says. Take it from the architect.

This story was originally published in the spring 2025 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.