'Aim high, have fun,

'Aim high, have fun,

and find joy'

Principal Rawson rings in the school’s 245th year — and his last at the Academy.

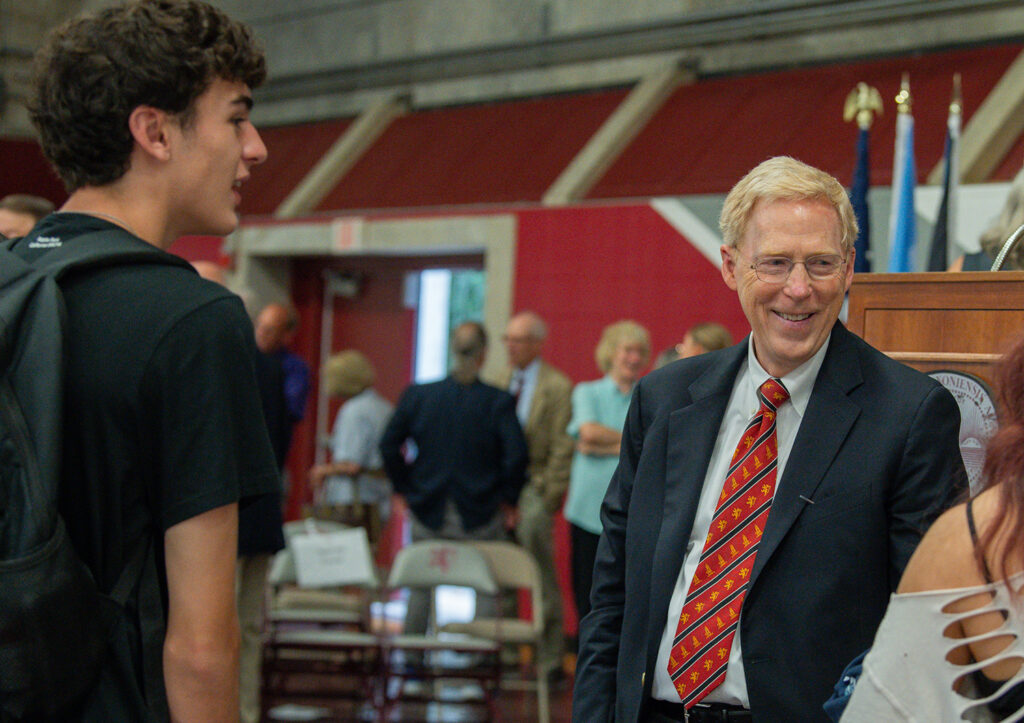

A buzz filled Love Gymnasium on Friday as Principal Bill Rawson ’71; ’65, ’70 (Hon.); P’08 welcomed students, faculty, staff and emeriti to the Opening Assembly of Exeter’s 245th school year. Students rose to their feet and applauded as the faculty proceeded into the gymnasium to start the ceremony, followed by a line of students bearing flags from the 40 countries represented in Exeter’s student body.

Assistant Principal Eimer Page, Dean of Faculty Meg Foley and Dean of Students Ashley Taylor joined the principal onstage for the assembly. Foley introduced this year’s new faculty members and the five longest-serving faculty members, while Page honored some of the Academy’s distinguished emeriti faculty, all of whom stood to be recognized by the audience.

Principal Bill Rawson ’71; ’65, ’70 (Hon.); P’08 encouraged the Academy to lead with empathy throughout the school year. Rawson, retiring at year’s end, delivered his final Opening Assembly address as principal.

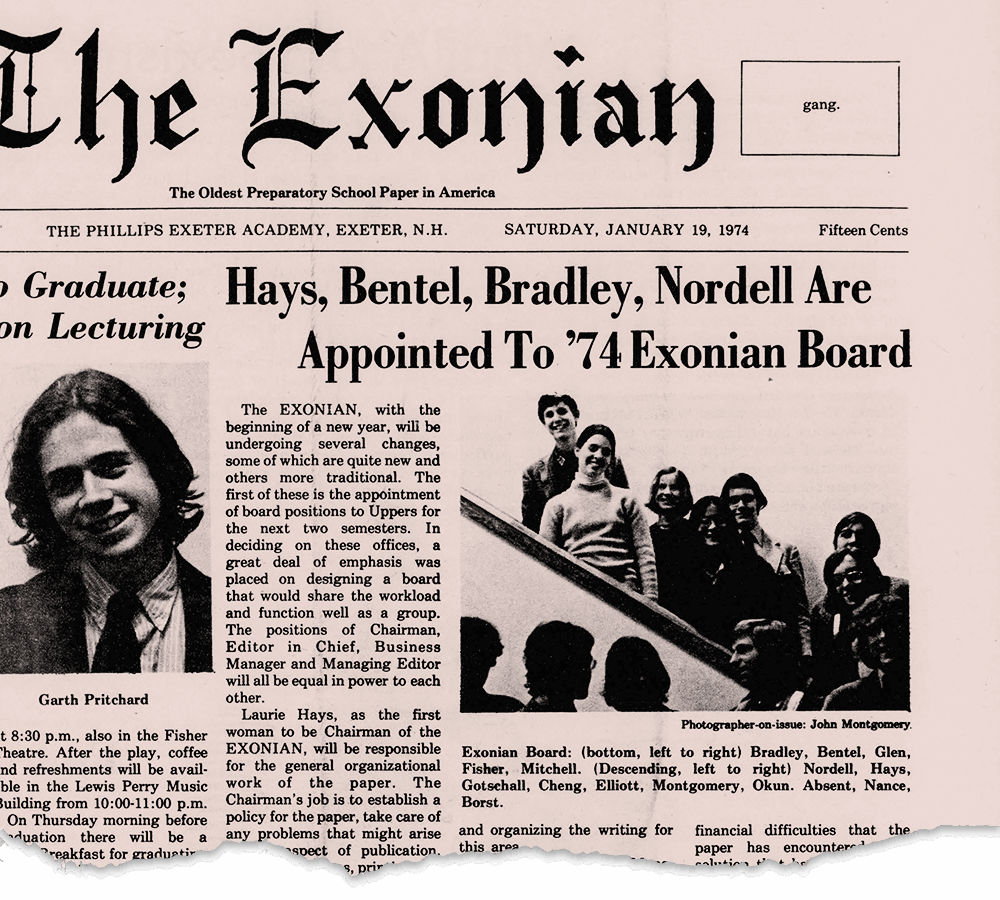

I found my life’s passion, and a good way to hide from academics, at The Exonian. I vividly remember the day that Roy Cohn ’74 said to me, “We have chosen you to be the first woman chairman of The Exonian because it’s about time for a woman to lead the paper.” (He might have said “girl.”) He made sure to clarify that this was not a DEI decision, adding, “We also think you are the best person for the job.” Thank you, Roy!

I found my life’s passion, and a good way to hide from academics, at The Exonian. I vividly remember the day that Roy Cohn ’74 said to me, “We have chosen you to be the first woman chairman of The Exonian because it’s about time for a woman to lead the paper.” (He might have said “girl.”) He made sure to clarify that this was not a DEI decision, adding, “We also think you are the best person for the job.” Thank you, Roy!