Shared Space,

Shared Space,

Shared Future

The renewal of Exeter’s Academy Building and venerated Assembly Hall

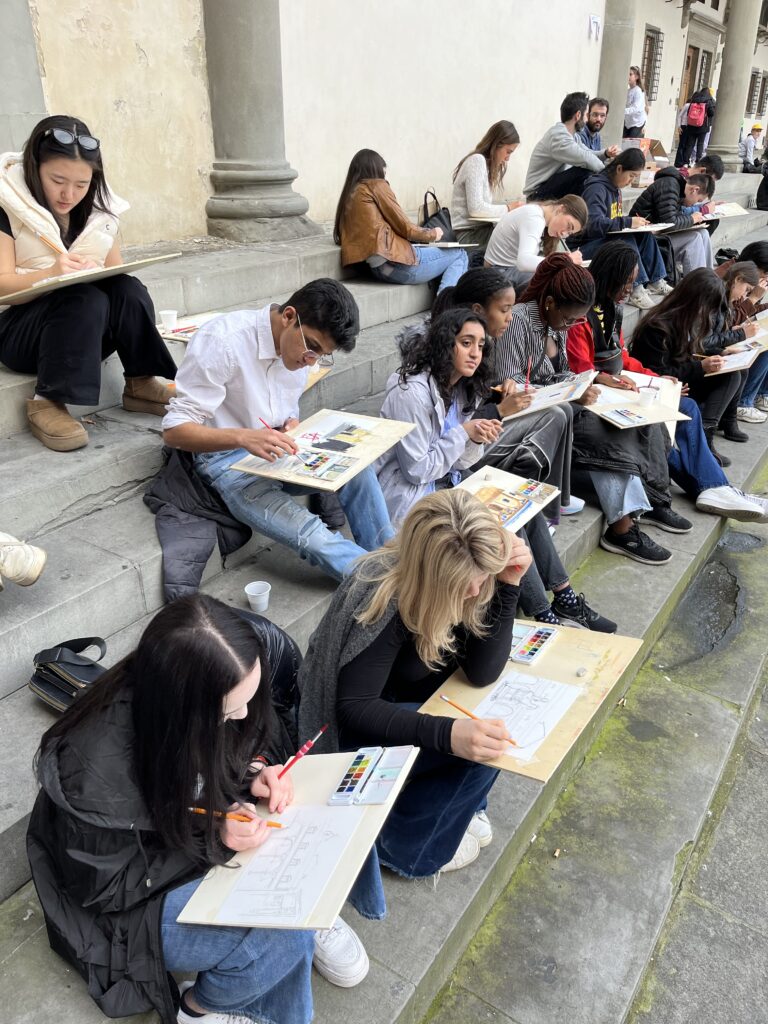

The air was thick with anticipation of the school year’s end and the summer ahead one late-spring day when the temperature climbed above 90 degrees. As students gathered in the Academy Building for the last all-school assembly of the year, historical photos of Assembly Hall flashed on the projection screen. It was a clue that this assembly not only would feature the traditional student speakers and slide show celebrating the graduating class, but also would hold a deeper significance.

The concert choir sang two numbers that morning, including “Rest” by Ralph Vaughan Williams. The choice was appropriate for a space that would be “placed away, but returned to in a few brief months,” said choir director Kris Johnson, the Michael V. Forrestal ’45 Chair for Music.

This was the last assembly in the hall as the Exeter community has known it for more than five decades. A planned two-year renovation of Assembly Hall and the Academy Building began that afternoon.

“This room is about to change, but our purpose in coming to assembly will remain the same,” Principal Bill Rawson ’71 said. “We say goodbye to this room with some sadness because of the experiences we’ve had here and our familiarity with the room. We also are excited to imagine what assemblies will be like when all students and faculty can attend in person in a beautifully expanded and restored space and … with air conditioning.”

For the final time before the new Assembly Hall opens, Rawson dismissed students with a resounding “senior class!”

Academy Building Over Time

From the time Exeter welcomed its first 56 students in 1783, an Academy Building has served as the center of academic and community life on campus.

1782-94

Exeter’s first students and faculty share four classrooms in this two-story wooden school house on Tan Lane. It has expanded and moved several times, finally settling on Elliot Street in 1999.

1794-1870

As the school grows, a larger Academy Building is built along Front Street. The Georgian-style building serves the school for nearly 80 years before a fire destroys it.

1872-1914

The third Academy Building is designed to replicate the second as closely as possible, but in brick. Academy chronicler Frank H. Cunningham describes it as “perfect in its proportions and graceful in its outlines.” The building nonetheless meets the same fate as its predecessor.

1915-2025

In the wake of another devastating fire, Exonians raise $200,000 — some $6.2 million today — for the construction of a fourth Academy Building. It incorporates nearly 1 million water-struck bricks and white Vermont marble. An addition to the north side is built in 1931. An update is completed in 1969.

2025-

Construction begins on a comprehensive renewal of the Academy Building that preserves its historic character while expanding and reimagining it for Exeter’s future.

Academy Building by the numbers

Approximate number of required assemblies each year

Seating capacity of the new Assembly Hall

Square feet of the new Design Lab

Number of geothermal wells serving the Academy Building, Phillips Hall and the renovated dining hall

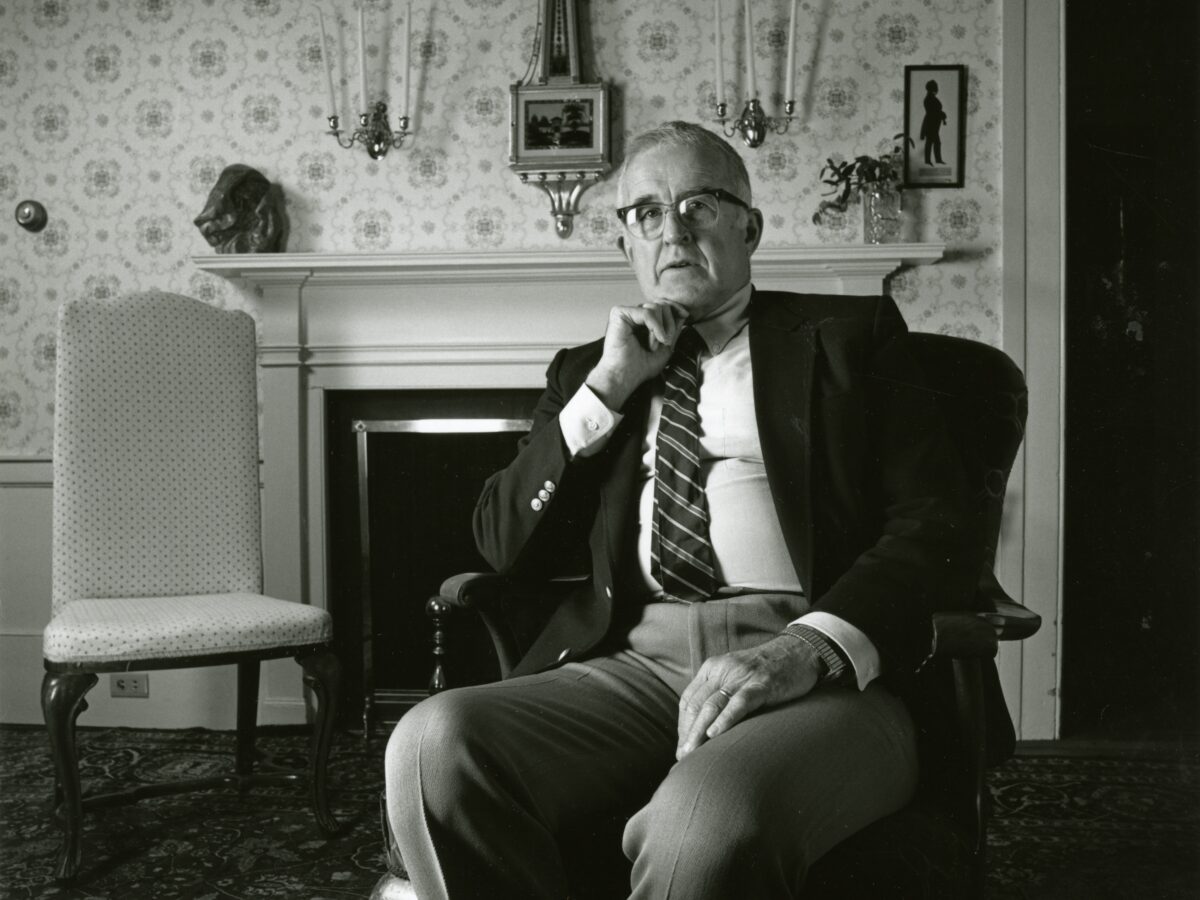

As the project moves forward, 35 portraits that hang in the Assembly Hall were taken down and stored for safe keeping.

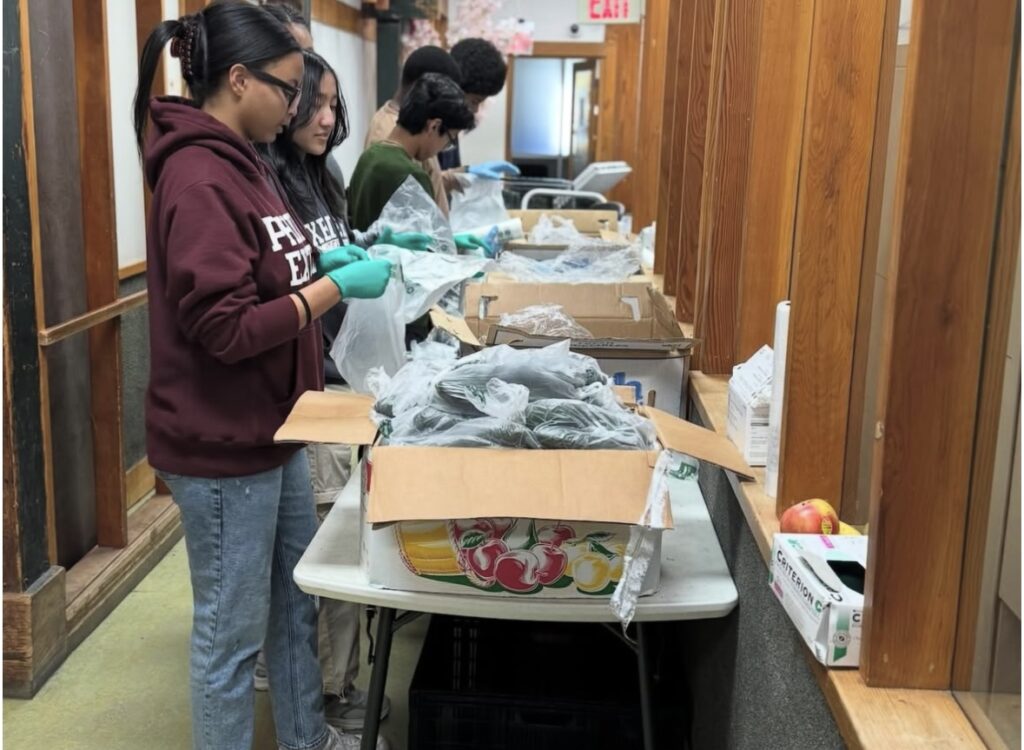

Inside the Academy Building (clockwise from left) The marble staircase will be preserved and restored. A new 2,600-square-foot Design Lab will offer students an expanded and permanent makerspace.

Behind the Lectern

Behind the Lectern

The politicians, writers, scientists and luminaries who have graced the stage

For decades the Academy has hosted a who’s who of speakers on the Assembly Hall stage. Tastemakers from the world of politics, writing and business have recited tales of accomplishments or provided messages of inspiration for the impressionable audience.

“What is consistent with the assemblies I love wasn’t the topic, but the speakers’ energy,” Morgan Momen ’27 says. “Being exposed to great speakers in high school gives us a head start and allows us to take note of what works in other people’s speeches and apply it to our own.”

In the lead-up to his successful presidential campaign, Jimmy Carter spoke to Exonians in February 1976. Eight days later, his successor, Ronald Reagan, did the same. Presidential runners-up Michael Dukakis and Bob Dole each made appearances in the late ’80s. Others from the political sphere like civil rights leaders John Lewis and Julian Bond, Carol Moseley Braun and Ron Paul have all spoken at assembly.

Authors who have spoken at Exeter include James Baldwin, Arthur Miller, Doris Kearns Goodwin, Jorge Luis Borges, Gwendolyn Brooks and poet and four-time Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Frost, who was a regular assembly speaker throughout the first half of the 20th century. Alumni authors Gore Vidal ’43, George Plimpton ’44, John Knowles ’45, John Irving ’61, Dan Brown ’82 and Roxane Gay ’92 have graced the Assembly Hall stage, with Brown delivering an annual address to preps in recent years. Academics Noam Chomsky, Henry Louis Gates and Cornel West and scientists J. Robert Oppenheimer, Jane Goodall and Sylvia Earle are all part of the storied list of assembly speakers.

“If you were to think about the people who have spoken onstage, and the impact they have had on student lives, it’s really powerful,” Principal Bill Rawson ’71 says.

Which assembly speaker do you remember? Share your memory with us at bulletin@exeter.edu.