One of the first things I noticed in the classrooms where I was learning Latin and ancient Greek is that, in high school, I was one of the few students of color. And in college, in some cases I was the only student of color. And this served as a pretty swift education in the politics of accessibility and, crucially, in the many different structural impediments that arise and that are systematically perpetuated in the face of those who might be interested in learning the language but who happen to be brown like me.

Yeah. I think I’m the only Latinx student in the classics in my grade. What other conflicts emerged by being the only one, or one of the few, who studied the language?

The resistance that was most tangible and, in some respects, most immediately compelling came from some of my close friends. I was involved in Latinx stuff on campus and counted among my close friends some of the folks who had profiles that are very similar to mine.

We were all first-generation immigrants and/or children of immigrants. And there was this pretty significant fissure that opened up in our friend group, around the time when sophomores were declaring concentrations or majors, between people who thought that it was important to concentrate in a field that was practical and that could set us up to do public-facing and activist work, and folks who thought, “I’m here at Princeton. I can do whatever the hell I want. This is what this education is supposed to be.”

So, when one of my friends and I were discussing our decisions to major in classics or major in comp lit or major in French, our third friend interjected and really chastised us. He said, “What are you doing with this blanquito stuff? You’re just majoring in these white people fields.”

The point that my friend was making was not actually a trivial one. It had to be taken seriously because there was this big issue of, well, how do we take our education in classics and make it into something that can be public-facing? And how … do I move productively in this space and seek, in classics, resources for the liberation of my folks, right? And that became the most urgent question that guided me through my undergraduate years and beyond.

How do you think that I, who am not as well-versed in the classics, could bring the classics back to my community and help them?

[The] classics can be useful to you in your negotiations with your community if you proceed from the assumption that you are sharing something that will then serve as a site for mutual sharing and exchange, and that they may have much more to teach you about classics than you will have to teach them.

Because they, your community, the communities in which you grew up, the communities in which I grew up, they are hard at work continuously re-elaborating their own classicisms. They have an understanding of their histories and those histories utilize some of the same conceptual structures that you learn in these classrooms. Right? So they’re classicists too.

What’s the future for you in the classics and what do you think the future is for the classical languages?

I worry about the future. Is there a future? Well, assuming that we don’t die in some nuclear holocaust in the next 10 years, or that the environment does not completely implode on us, although it certainly will, I see my future as proceeding down several parallel paths.

My work in Roman history will continue to be at the core of how I identify myself as a classicist. That work is very much driven by attention to questions of human mobility, human forced mobility, enslavement and trafficking, and how these are recoverable from the various sources at our disposal, not just in connection with the Roman Mediterranean, but in other free, modern Imperial systems.

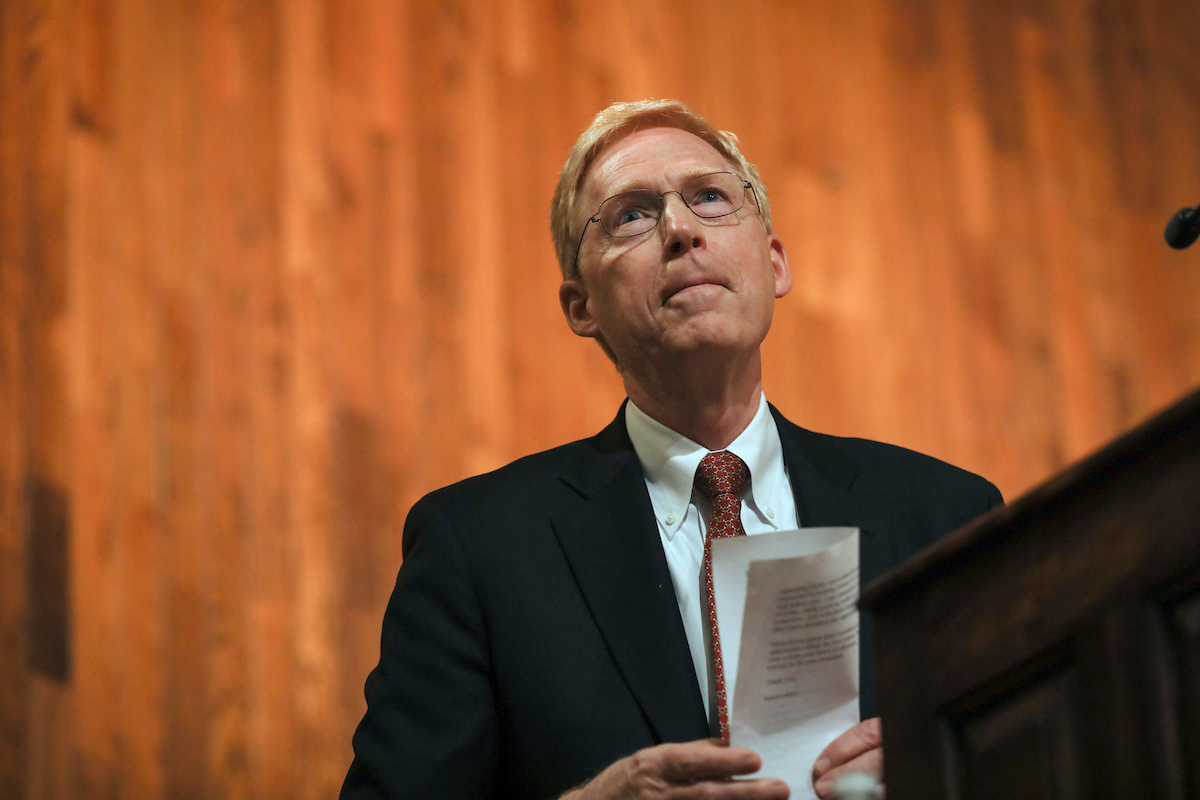

I am also committed to continuing the work that was begun in the memoir itself and that work, as I see it, consists both of a concern for the public face of scholarship and a heightened awareness of how this lived and embodied experience can and should move to the forefront of public conversations about classics.

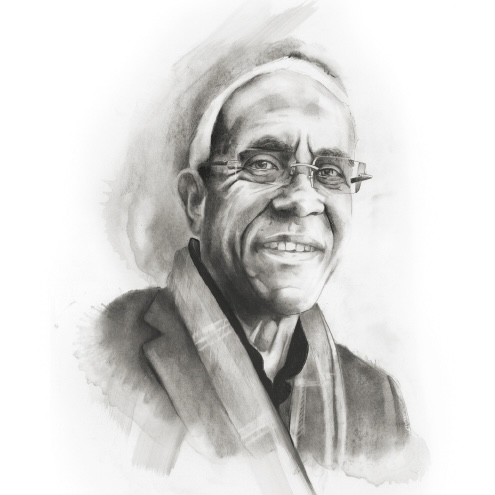

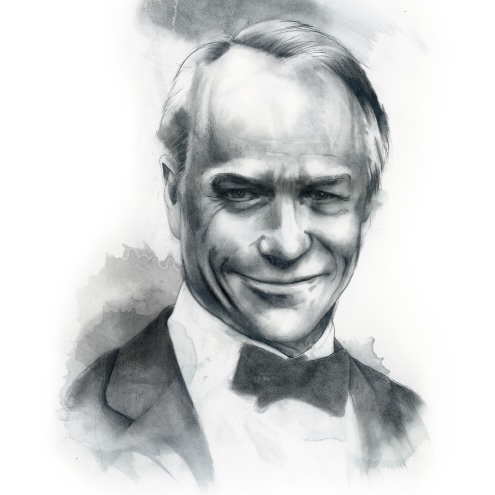

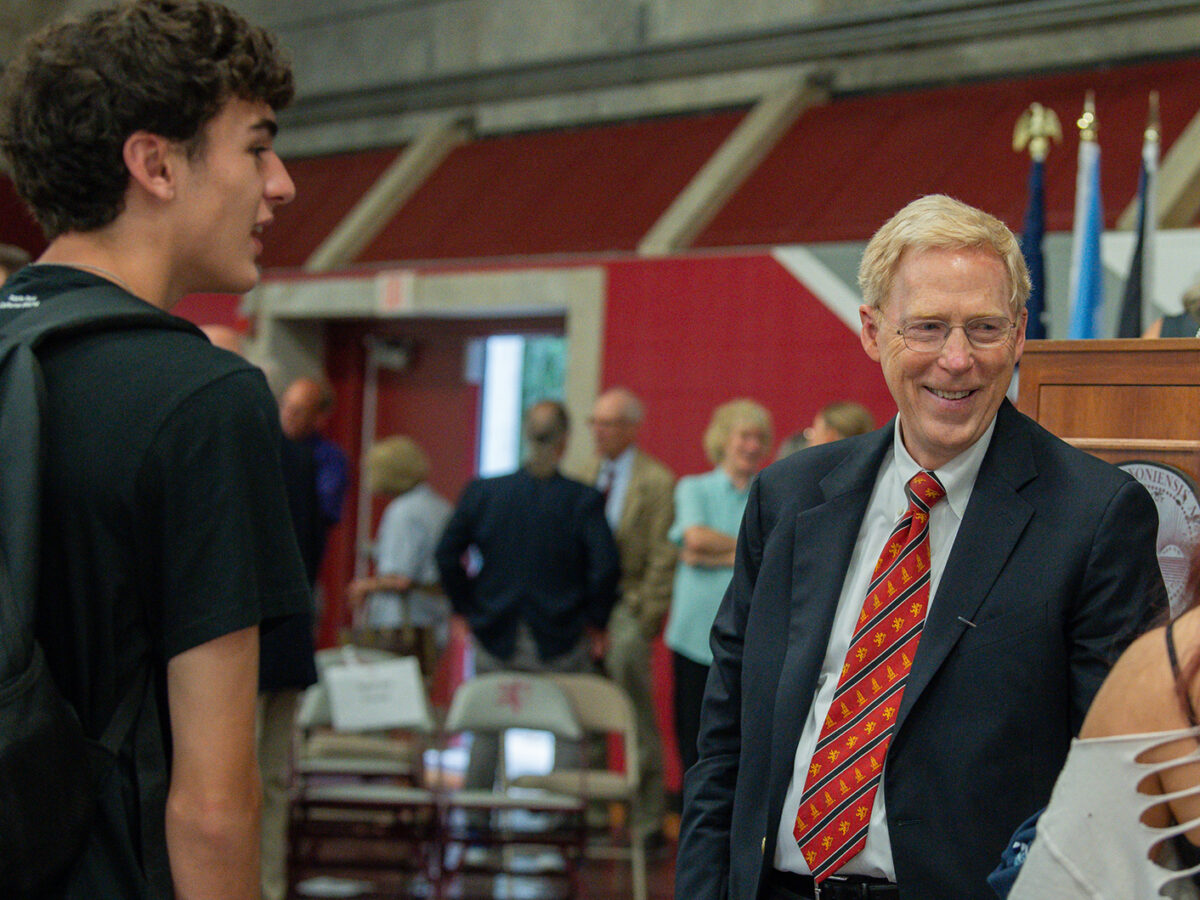

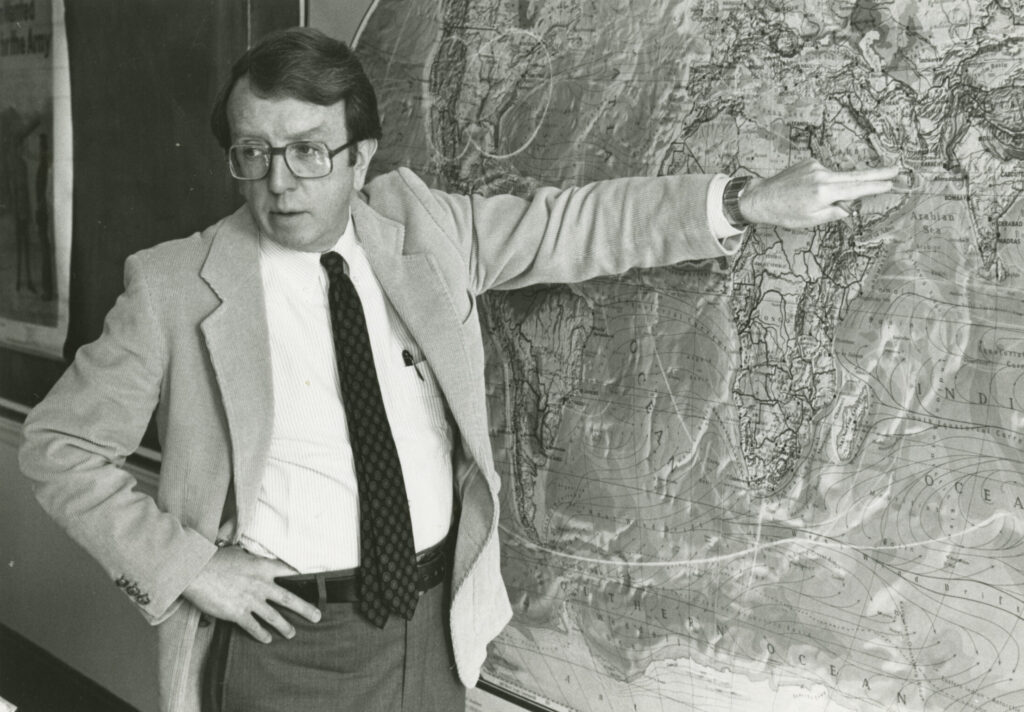

So, when folks think of classics, I would want them not to think about, say, white men like the ones in this room [referring to portraits hanging on the walls]. I would want them to think about folks of color, and I want their default image to be folks of color. And I want that to be their default image because I want them to recognize that the classics … is not really about the ancient Greeks and Romans, and it’s not really about dead white men because the Greeks and Romans weren’t white. They would have not really understood our racial categories.

They have been constructed as white by centuries of scholarly discourse.

I would like to see more direct and concerted grappling with this: How is whiteness itself an artifact of a particular configuration of scholarly practices that rely, in part, on the association of Greeks and Romans with early modern Europeans who saw themselves as the heirs of Greece and Rome and [who] simultaneously claimed a heritage in ancient Greece and Rome and, at the same time, assigned the Greeks and Romans racial attributes, which were then deployable and weaponizable against folks who were deemed not white?

The last aspect of the future of classics, and of my future in it, has to do with … whether classicists need to be better at interrogating the racial underpinnings of their practice.

Johan Martinez Arriaga is from Chicago and is a co-head of the Afro-Latinx Exonian Society, and a proctor in Main Street dorm and the Office of Multicultural Affairs.