By contrast, Delgado had only six students in Transition Spanish for Heritage Speakers when it launched in the fall term, but he predicts that number will grow. “The Hispanic population is rising in the United States, and we are going to be dealing with a very big number of students in similar cases,” he says.The growing number of heritage language classes at secondary schools and universities across the country reflects the reality that the United States is increasingly becoming a bilingual country. According to a 2021 report by the global nonprofit organization Instituto Cervantes, the United States has the world’s fourth-largest Spanish-speaking population (counting only native Spanish speakers). By 2060, Instituto Cervantes estimated, 27.5% of the U.S. population will be of Hispanic origin, making it the country with the world’s second-largest Spanish-speaking population.

At Exeter, Hispanic/Latino students currently make up around 8.2% of the student body, according to self-reported surveys conducted by the Admissions Office. But the number of students who fit the heritage speaker of Spanish profile is growing, Pérez-Andreu says, leading to the introduction of the course this year.

Jackie Flores, who has taught Spanish at Exeter since 1997 and oversees the Spanish language placement tests for incoming students, argued strongly for the addition of a heritage Spanish course. “I taught the 100-level course for many years, and I always found it so uncomfortable having that one Latino or Latina student who stood out, and everybody around the table either feeling intimidated or thinking, ‘Why is this student in my class? Don’t they already speak Spanish?’” She has also seen many Hispanic students skip learning Spanish altogether because they think they already know the language.

Patrick Snyder ’25 nearly became one of those students. Throughout his childhood in San Antonio, Texas, Snyder says, his mother, who is Mexican, spoke Spanish to him, but he would never speak back. When he enrolled at Exeter as a prep, he decided to take Chinese. “I wanted to challenge myself, I guess,” he recalls. Last fall, he made the switch to the new Spanish for Heritage Speakers course. “I’ve loved it,” he says. “Having that half-Latino in me, I love learning the language and getting into the culture more.”

Like Snyder, other students in the class report that their relatives spoke to them in Spanish from an early age and that they answered only “ in English. “I’ve always been able to understand what people are saying, but being able to speak and write is a whole different thing,” says Celia Valdez ’26, whose father is Chicano and whose mother is of mixed Cuban and white heritage.

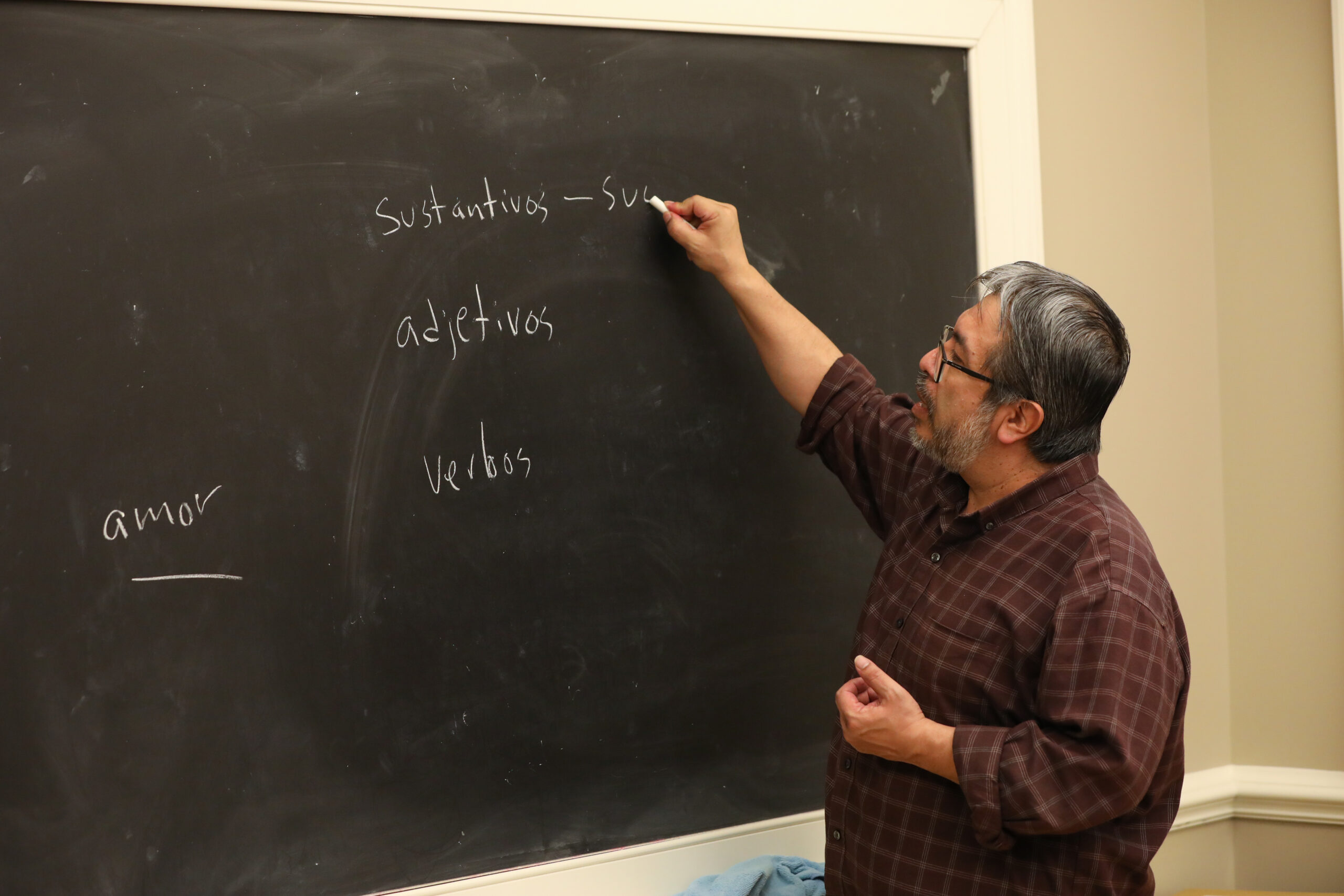

One problem, Delgado says, “is that Spanish in the United States has been stigmatized in general.” A native of Mexico, he came to Exeter in 2020, after teaching Spanish and Latino Studies to undergraduates at Harvard University and Boston College. He adds: “These kids are often reluctant to learn Spanish because they have learned that Spanish is second in language, second in culture. This is the other thing you have to create: a pride for the language and their cultures, their heritages.”

Albinson is now taking SPA503: Family, Community and Contemporary Life. “My language requirement will be fulfilled by the end of this term, and that’s all thanks to being in the heritage class.” He plans to use the increased flexibility to polish his Spanish through more classes, and to take electives like epistemology, anthropology and economics.

Albinson is now taking SPA503: Family, Community and Contemporary Life. “My language requirement will be fulfilled by the end of this term, and that’s all thanks to being in the heritage class.” He plans to use the increased flexibility to polish his Spanish through more classes, and to take electives like epistemology, anthropology and economics.