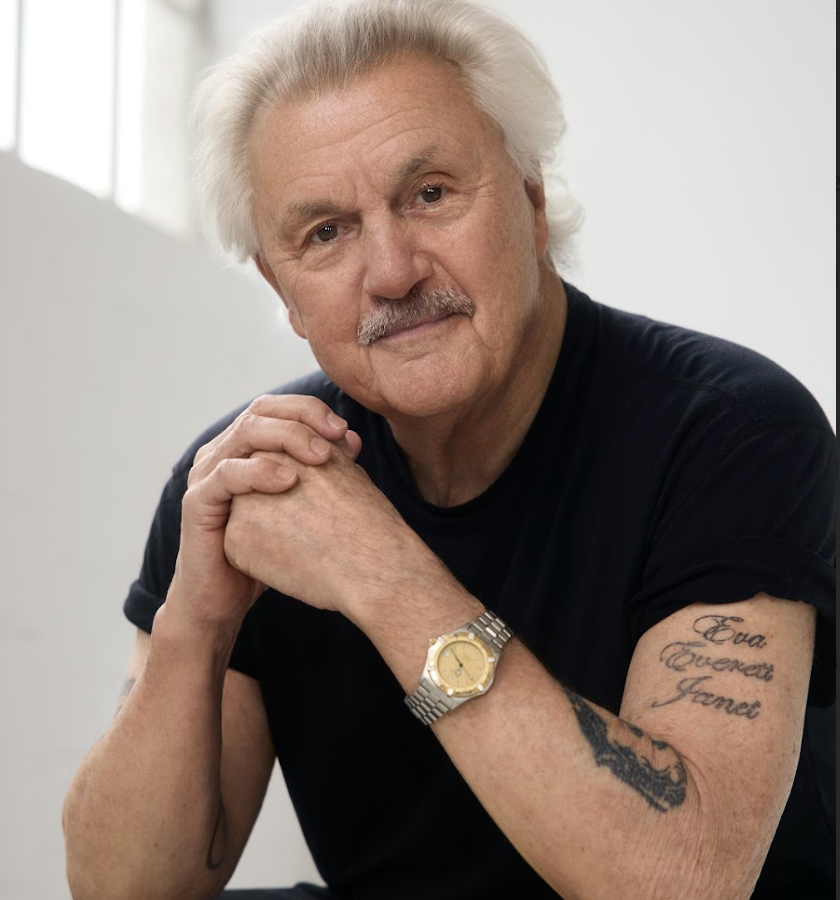

Identity, Belonging, History: A conversation with novelist John Irving ’61

For fans of author John Irving ’61, his most recent novel provides a host of familiar comforts: tattoo parlors, Viennese romps, unconventional family dynamics and, of course, a thinly veiled version of Phillips Exeter Academy. But that novel, Queen Esther, also ventures into uncharted territory, especially when tracing the enigmatic exploits of its titular character, a Jewish orphan named Esther Nacht. Irving — a standout wrestler at Exeter and a lifelong devotee of the sport — discussed his new book with current varsity wrestling coach Justin Muchnick. Here’s some of their conversation.

Let’s start with your main character, Esther. How does she drive this novel?

Esther is born in Vienna in 1905. By the time she’s a 3-year-old, her life has already been shaped by antisemitism. She returns to her birth city in the 1930s, when many Viennese Jews are leaving (or have already left). I wanted my Esther to be the embodiment of the Esther in the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. She is the epitome of hiddenness — a secretive, behind-the-scenes operator. But when she reveals herself, watch out! Esther is making up for the Jewish childhood she was denied; she’s going to be the best Jew she can be. I wanted her to be part of the founding of the State of Israel. Her birth child, Jimmy, is my POV character, but Esther is the novel’s main character; she’s the one who makes everything happen. The objective of this ending-driven novel — which concludes in Jerusalem in 1981 — was to create, in Esther, an empathetic Zionist.

On that ending: Why Jerusalem, and why 1981?April 1981 is when — in my life — I was invited to Israel by the Jerusalem International Book Fair and my Israeli publisher. I accepted the invitation at the urging of my favorite European publishers. They were Jewish with longstanding ties to Israel. They were leftist, nonobservant Jews who’d criticized the right-wing Likud government of Menachem Begin for accelerating the settlements in the West Bank. They said the Israeli presence there, and in the Gaza Strip, might make Palestinian self-determination harder to achieve — they believed then that a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict could slip away. Queen Esther is a historical novel, and a historical novel foreshadows the future. In April 1981, the seeds were sown for an eternal conflict.

It’s a conflict that’s taken on a renewed relevance in recent years — perhaps more than you were expecting during the writing process.

The novel has certainly predicted that these troubles were likely to be ongoing. Of course, I wish for a peaceful resolution. I’m hoping for a lasting peace, for the Israelis and the Palestinians.

When researching this book, did you visit Israel? Have you been back since 1981?

It was important to me that I not go back to check my facts — not until I had a finished draft. The dialogue mirrors what I remember being said to me, or what I overheard. But in a historical novel, the dialogue must also be what was commonly said in that time and place. My early readers — several Israeli contacts and friends — assured me it is.

Once the novel was drafted, in July 2024, I visited Jerusalem, to talk to these early readers and to refresh my memory of the visual details — to go where I’d gone 43 years ago. When I was there in 2024, the war in Gaza was ongoing. In the Muslim Quarter, there were no tourists on the Via Dolorosa — the Way of Sorrows, where Christ carried the cross to be crucified. No tourists in the Christian Quarter — not even at Christ’s tomb, in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. I was alone in the evenings, reading over my day’s notes, mapping out where I would go the next day. Most evenings, my Israeli friends were at anti-Netanyahu protests.

Backtracking from your novel’s ending to its beginning: You included a cameo from Dr. Wilbur Larch, the saintly abortionist-cum-orphanage director from The Cider House Rules.

The beginnings of my novels are often the most autobiographical. I’m conscious of grounding my novels in recognizable locations, and with some familiar character types, but this is the first time that I have re-created or revisited an old character. The reasons for doing so had everything to do with my trajectory for Esther. I needed an orphanage for an abandoned Jewish child. I knew of an orphanage where she would be treated well.

Dr. Larch is much younger than readers or moviegoers who know The Cider House Rules will remember, and there’s an entirely different cast of characters among the unadopted orphans, but I knew Dr. Larch would find out all he could about Esther, and that he’d find the best possible family for her, although they wouldn’t be a Jewish family.

I love Dr. Larch but, for obvious reasons, I’ve got a soft spot for the novel’s wrestling scenes. You’ve set these in Vienna, in a grimy but cosmopolitan gym called the Turnhalle Leopold.

I tried to be truthful to the wrestling gyms I visited when I was in Vienna in 1963–64. At that time, there were more Greco-Roman wrestlers than freestyle wrestlers — freestyle being closer to folkstyle in the U.S. Because Queen Esther is a political novel, I chose to focus on two Soviet and two Israeli wrestlers as characters. Some of the Soviets in Vienna in ’63-’64 were KGB operatives, and some of the Israelis were Mossad operatives — or “working for Wiesenthal” as Nazi hunters. In the novel, I wanted the Soviets and the Israelis to be the only wrestlers that my character Jimmy was close to.

You’ve seen a lot in the sport, both as an athlete and as a coach. So, from one coach to another, what’s your go-to piece of coaching advice?

I was lucky to be associated with excellent wrestling coaches, all in first-rate programs. This began with Coach Seabrooke at Exeter (a Big Ten champion at Illinois, and a two-time NCAA finalist), and it continued when I was at Pittsburgh and Iowa. Great clubs, great coaches. Many of my teammates and workout partners were champions — and so were my sons, both of whom I coached. My son Colin won a New England Championship for Northfield Mount Hermon; my son Brendan won the same title for Vermont Academy. But I, as a wrestler, never got past the semifinals at any tournament — in my Exeter years, in my university years or postcollege.

My foremost advice to a coach, at any level, is you have to know who the superior athletes are, and you have to recognize the hard workers who aren’t as gifted athletically. You coach to the individual. A good athlete will end up on top in a scramble; you coach that guy differently than you would a wrestler who’s not as talented. Some guys thrive in scrambles; other guys get killed in them. Know the difference!

—Justin Muchnick is the varsity wrestling coach at the Academy and a Ph.D. candidate in classics at the Institute of Classical Studies.

This article was originally published in the winter 2026 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.