Cabinets of

Cabinets of

Curiosities

Exeter’s vast and distinctive specimen collections spark active learning and exploration.

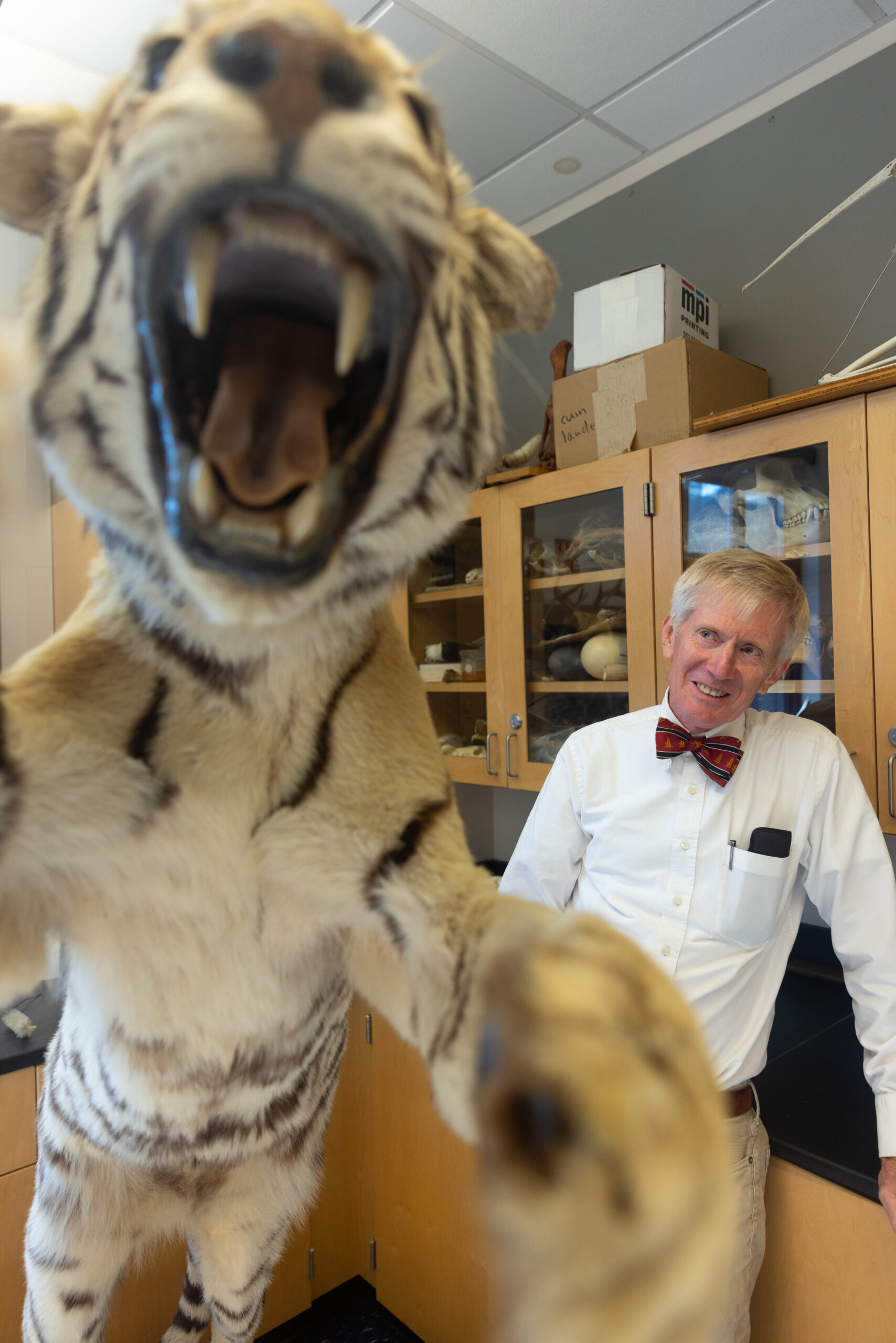

A towering taxidermy tiger. Brain matter suspended in acrylic. A fossil more than 140 million years old.

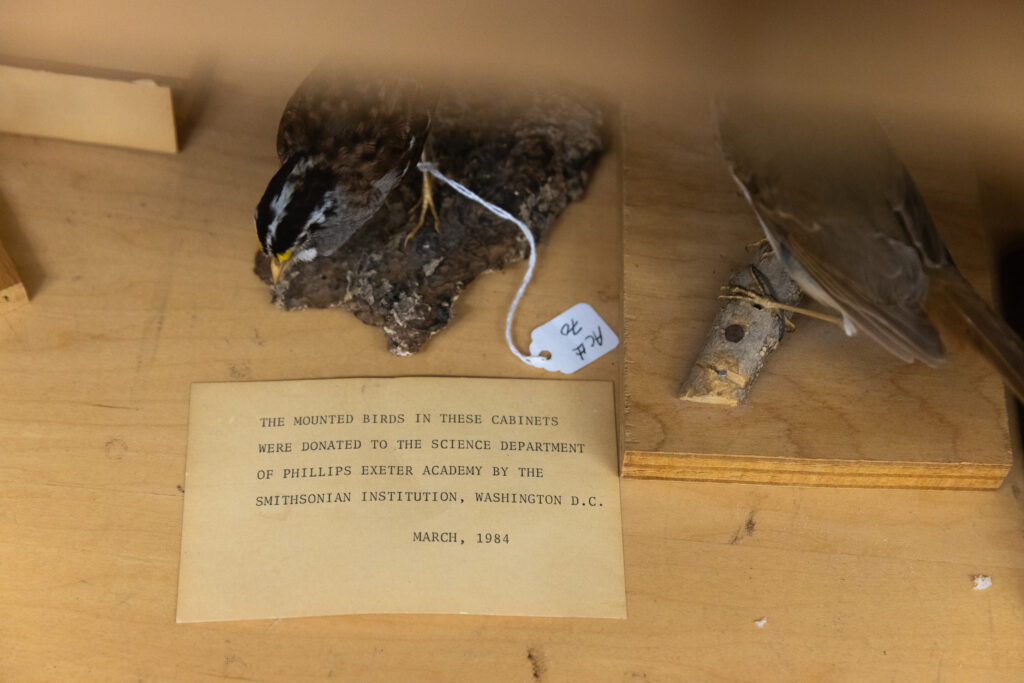

These are just a few of the treasures tucked away in drawers, shelves and cabinets in the Phelps Science Center. Handled by students across disciplines, the specimens — including skins, skeletons, fluid-preserved animals, pressed plants and rocks — are a fundamental component of science research and instruction at Exeter.

“It is kind of unique to have something like this accessible at a high school level,” Science Instructor Chris Matlack says of Exeter’s bird skin collection. “The kids are getting classes here using collections that, frankly, they’d have to wait for a particular university to see.”

Instructors say the collections are invaluable as they help students grasp the scientific method, connect abstract concepts to real-world examples and spark curiosity.

“Natural history collections are what got me excited about biology growing up just a few blocks from the American Museum of Natural History in New York City,” says Scott Edwards ’81, professor of organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard and curator in ornithology at the university’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, which holds approximately 21 million animal specimens. “The fact that Exeter had a specimen collection was really important to me.”

Edwards has seen the positive influence the collections can have with his own students. “They love handling the birds and being able to look at them closely,” he says. “Because that’s what you need to do to really understand a species. You need to be able to look at the details of the feather morphology, how the feathers line up along the wing margin, the precise shape of the head and bill, the webbing on the feet. It’s these details that make natural history collections important for students.”

Even in the digital age, specimen collections remain just as vital today as they were when biologists began preserving them more than 200 years ago — perhaps even more so.

“Specimens provide really important windows into how species have been affected by humans, including climate change and environmental pollutants,” Edwards says. “Using specimens, we can see what chemicals an individual has encountered, and we can actually go back in time to when the specimen was collected and compare those individuals with individuals today to look for trends.”

Here’s a look at a few of the Academy Science Department’s extensive preserved specimen collections, including what they are, and how they are used in class.

Savannah sparrows contained in tubes for preservation; Instructor in Science, Chris Matlack; a mounted bird donated by the Smithsonian Institution.