Science Project

Instructor in Science Andrew McTammany ’04 explores the interplay between curiosity, assessment and student engagement

“Our daughter ate a rock,” I told my spouse as he returned from crew practice one afternoon. “I tried to stop her, but she’d swallowed it by the time I got there.”

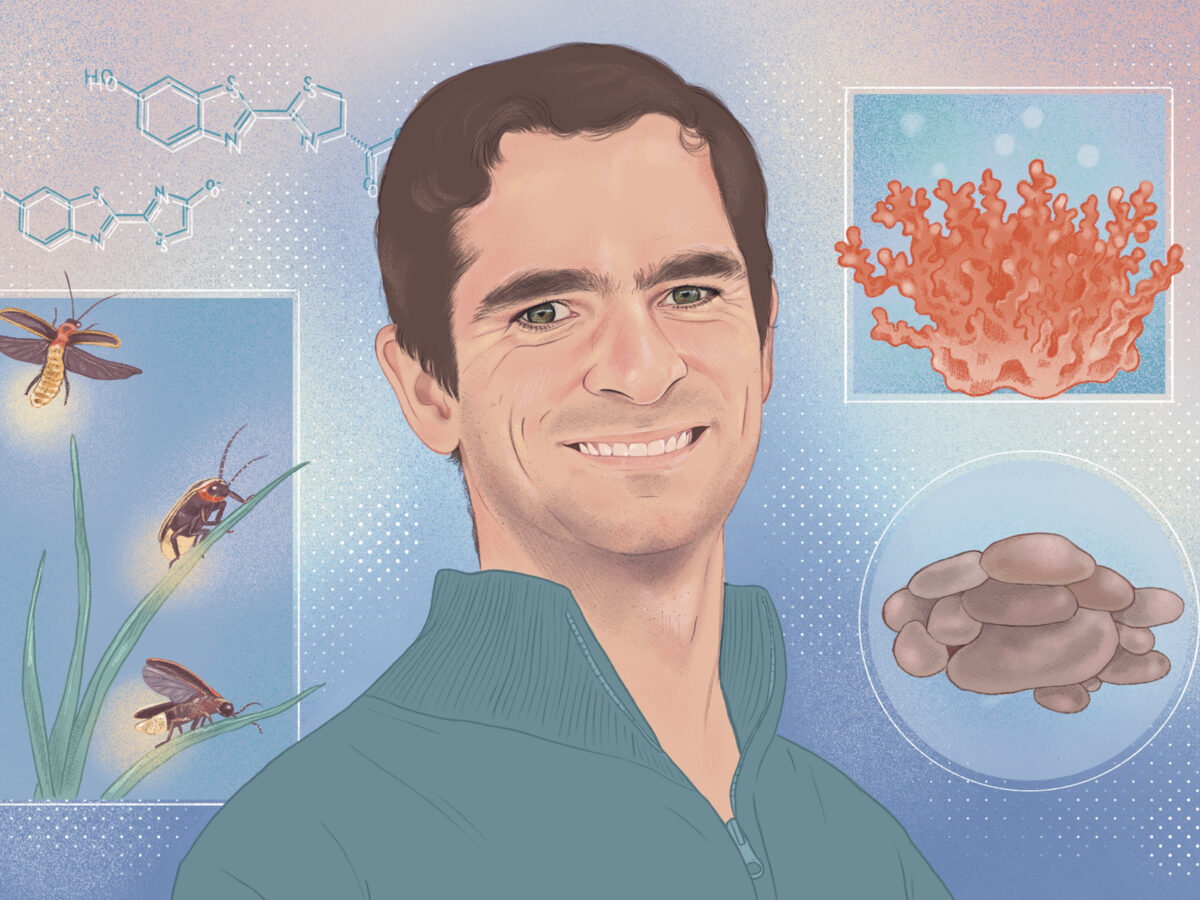

Curiosity is a strong, and sometimes uncontrollable, impulse. My daughter’s urge to taste a rock (honestly, it was a small pebble) is not much different from what piqued my interest in organic chemistry: the desire to know more about the world. Like my daughter — whose favorite phrase is “What’s this?” — I’m constantly asking questions. Mine are slightly different, and chemistry has been the lens that I’ve used to find answers. Why do fireflies flash at night? A reaction between luciferin and the enzyme luciferase. Researchers call this type of curiosity “joyous exploration” and have investigated its role in learning and motivation.

The most frequent response I get when I share that I’m a chemistry teacher is, “I hated that subject.” I never quite know what to say other than to list the course I dreaded most (history). But I often wonder, what is it about chemistry that elicits such a strong reaction, and is there any way to get students more excited to learn it?

Each spring, Exeter’s Center for Teaching and Learning asks for project proposals from faculty looking to research a topic during the following school year. Usually, I am a bit of a dabbler, a stone skipping across the water’s surface. A yearlong project seemed like a great way to focus on a single topic, to dig into the research on curiosity, assessment and student engagement, and hopefully to find a way to combat chemistry’s PR problem.

During the fall term, I wanted to learn how students felt while completing chemistry homework, studying for exams and working at the lab bench. It came as somewhat of a surprise, but most students said they enjoyed learning the topic and some even found the subject interesting. They just weren’t too keen on studying for the tests. They reported feeling nervous, anxious and “cooked,” and constantly worried whether they had studied enough. And most students wanted more practice — practice tests and problems to help build their confidence. Maybe chemistry wasn’t the problem, and it was the tests that left a bad taste. Perhaps a different type of assessment could improve student engagement.

Instead of tests and lab reports, I asked students to explore a topic of their choice and explain it the way a chemist would. For another assignment, students created a small art exhibition inspired by the concept of entropy. I hoped that they would enjoy these projects, worry less and feel more confident in themselves.

The students amazed me with their wide range of topics — such as coral, diet soda and ceviche — and their projects. One senior made a video of her interpretive dance of statistical thermodynamics. Another mixed and layered two songs to create an acoustic interpretation of entropy and disorder. A third showed a video of lightning bugs blinking synchronously in an Appalachian forest and explained to the class how chemiluminescence can produce something so cool.

Before my partner returned from the boathouse, I Googled “what to do if your child swallows a rock.” I wasn’t too worried, only wanting to fill in a gap in my knowledge. This is called epistemic curiosity. Directionless curiosity, like shoving a handful of pebbles in your mouth, is known as diversive curiosity. Turns out, when you blend diversive and epistemic curiosity, work can seem like play.

Illustration by Becki Gill

This article was originally published in the summer 2025 edition of The Exeter Bulletin.