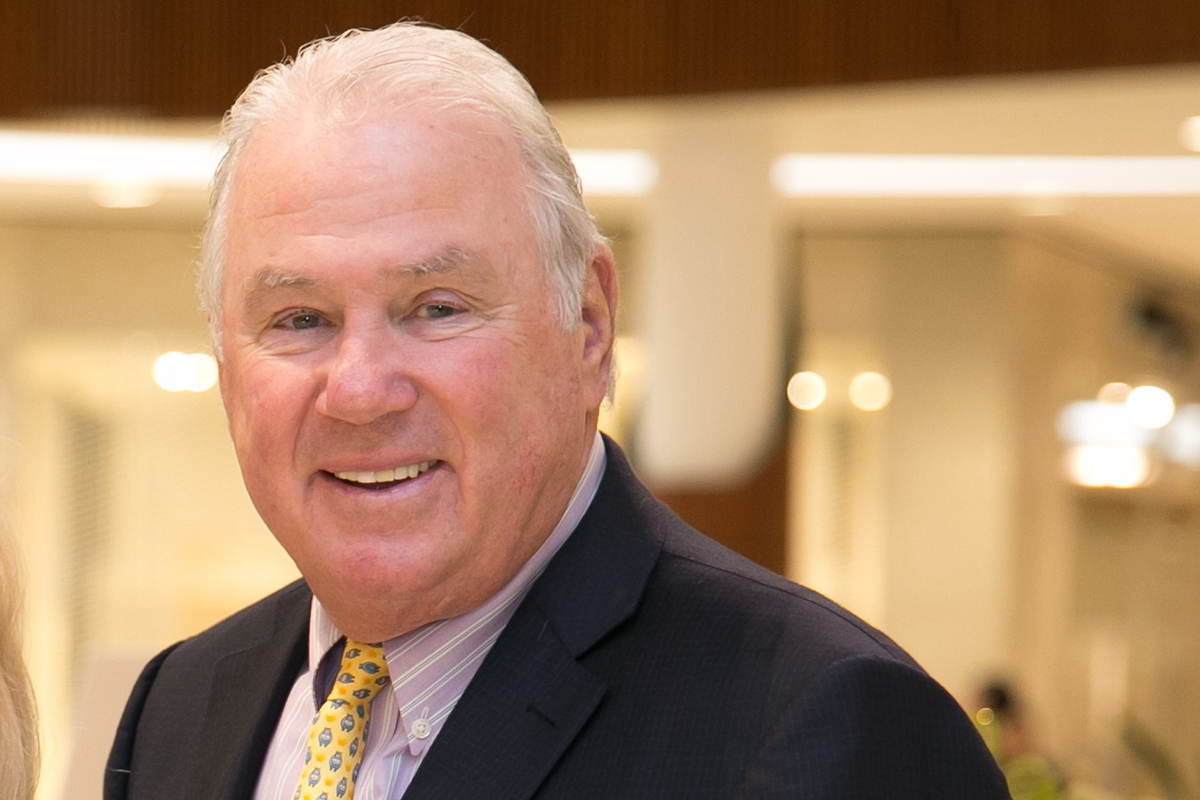

Joe O’Donnell

One-time MVP of the Exeter baseball team Joe O’Donnell ’63 showed his son, Joey, how to hit the stitching off a ball. Yet he didn’t teach him to run the bases — Joey’s teammates did that for him. Because he was born with cystic fibrosis, by the time Joey’s legs were strong enough to beat a throw to second, his lungs were too weak, his body too easily fatigued.

Cystic fibrosis is an inherited disease that causes mucus to get so thick and sticky that it clogs airways, rendering breathing nearly impossible and triggering frequent lung infections. It also accumulates in the tubes between the pancreas and the small intestine, making it difficult for the body to absorb nutrients.

Today, newborns nationwide are screened for the disease, but that was not the case in 1974. Instead, Joey’s mother, Kathy, observing that something seemed wrong with her 3-month-old firstborn, took him to doctors until he was given the blanket diagnosis of “failure to thrive.” It wasn’t until a couple of months later that cystic fibrosis was pinpointed.

“It was like being hit with a tidal wave when we got that death sentence,” O’Donnell says. At the time, that’s pretty much what a diagnosis of cystic fibrosis was for children: The sole treatment options were drugs that worked only until the child developed resistance to them, and O’Donnell says he didn’t dare imagine his son would survive more than a few years. For a brief time, however, Joey grew and lived a somewhat normal life — he was elected class president in seventh grade, and had the lead in the school play — while cheerfully educating his classmates about the disease.

“He was very comfortable advocating for CF,” O’Donnell says. “He was that kind of kid — a very engaging, sparkly kid.”

In 1986, Joey died at age 12: “It was the end of a dream,” O’Donnell says. But rather than turn away from CF, the O’Donnells dug in and established The Joey Fund.

“It is by far the most important thing that I do. It is Joey’s legacy,” says O’Donnell of the fund, an independent organization that in 30-plus years has brought in hundreds of millions of dollars to support CF research. It’s also a family affair: The O’Donnells’ daughters, Kate and Casey, both of whom were born after Joey’s death, have been involved since they were young children. The organization hosts a dozen or so fundraisers annually, but its signature event is The Joey Fund Film Premiere. When it debuted 33 years ago, O’Donnell had wanted to create an experience that was different from the traditional dinner and speaker fundraising format. He decided to offer a casual reception with food supplied by area restaurateurs and a screening of a film not yet out in theaters.

The first year, 62 people attended. Last November, about 1,200 people got a sneak peek at Molly’s Game, an Aaron Sorkin movie starring Jessica Chastain, Idris Elba and others. The event netted $1.2 million for The Joey Fund. O’Donnell attributes such support to the motivating progress being made in treating the disease.

O’Donnell’s fish-out-of-water story of coming to Exeter carries its own hint of Hollywood. Growing up in Everett, Massachusetts, a blue-collar city in the shadow of Boston Logan International Airport, O’Donnell was captain of the football and baseball teams and an honors student at Malden Catholic High School. He already had a couple of Ivy League acceptances in hand when he met with Harvard’s director of admissions, who recommended a postgraduate year. O’Donnell, who had never heard of the Academy, admits to having adopted an “us versus them” attitude and was not the least bit interested. His parents, however, seized on the idea.

He arrived on campus in September 1962 bewildered, O’Donnell says, to find himself surrounded by so much green and greeted by a male cheerleader. That was Craig Stapleton ’63, who had been assigned to O’Donnell as a guide, and whose invitation to play squash (“I didn’t know it was a sport — I thought you ate it, and I didn’t like it, so I said no.”) was the beginning of O’Donnell’s slow realization that there didn’t have to be an “us” or a “them,” something he makes a point of conveying to young people today. The year affected O’Donnell so profoundly that at their 50th reunion in 2013, he and Stapleton, a former U.S. ambassador to France, announced a fund they were establishing to provide 10 gifts each year “to underwrite annual financial aid packages for one-year seniors and/or postgraduate students.”

After he graduated from Exeter and then Harvard College, O’Donnell’s career took some interesting turns: He coached baseball at Harvard and taught school in Everett before earning his MBA at Harvard Business School and serving as that school’s associate dean of students. He then founded Boston Culinary Group Inc. (originally Boston Concessions Group Inc.), a food service management company acquired by Centerplate in 2010. O’Donnell is chair of the merged company, which manages food service operations in 250 stadiums, ski areas, amusement parks and theaters nationwide. O’Donnell also founded Belmont Capital and owns Allied Advertising Agency and Kings Bowl America.

O’Donnell still finds time to be an active philanthropist, both regionally and nationally. Harvard’s baseball field and its head coaching position bear his name. He has also served on the university’s Board of Overseers and on the boards of the Children’s Hospital Trust, Malden Catholic High School, the Winsor School and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, among other organizations. He was named to President George W. Bush’s Advisory Committee on the Arts and served as chair of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Milestones Campaign in 2010, where O’Donnell helped the foundation exceed its original fundraising goal of $175 million by $75 million.

But it’s The Joey Fund that occupies much of his passion, energy and time. In addition to the film premieres, the fund hosts billiards nights; the annual Kings Cup bowling competition, in which private equity firms buy lanes; and Hot Dog Safaris, where people can eat all the hot dogs they want.

The efforts of O’Donnell and his family, and the fund’s staff and volunteers, have paid off.

The Joey Fund has raised more than $250 million to date. O’Donnell directs as much as 5 percent of those funds toward smaller gifts for Boston-area residents with cystic fibrosis, such as an air conditioner for a Bostonian who was struggling to breathe at home, and a stationary bike for someone who wanted to exercise regularly. The remainder, after administrative expenses, goes to the national Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, money that has played a very real role in supporting the research and development of breakthrough treatments. One such treatment is ivacaftor (brand name Kalydeco and developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals). It is the first therapy to actually address the cause of cystic fibrosis, rather than just relieve its symptoms. O’Donnell says another treatment is on the horizon, and that could potentially up the cure rate from 65 percent of cases to 95 percent.

“Things are looking good for the CF kids,” he says, acknowledging the work is bittersweet: “You can’t help but think if only [these breakthroughs] had happened 30 years earlier, things would be different for Joey.” Yet without Joey’s eponymous fund and his devoted parents, those successes might not ever have been possible.

— Sarah Zobel

Editor’s note: This profile first appeared in the winter 2018 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.