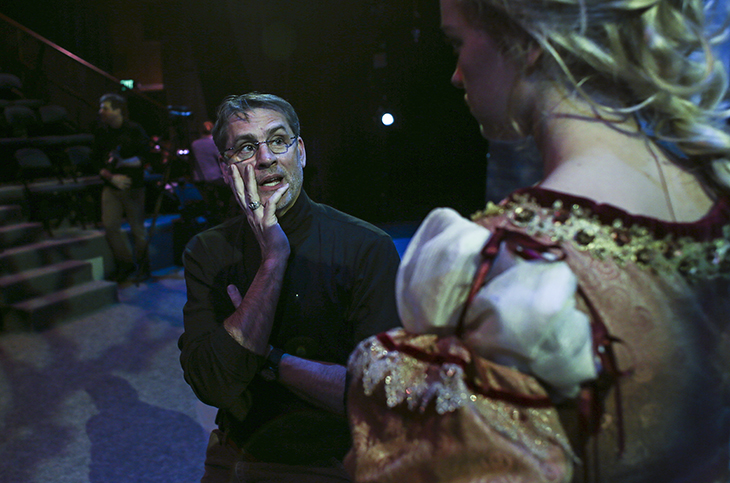

Rob Richards

You might say Rob Richards’ love of theater began in utero. His mother was a puppeteer, using elaborate marionettes to stage plays on the family’s property for years. “I was in her abdomen while she was performing,” he says, “and then backstage listening to all the voices.”

The plays were put on in the family barn — “we always had to have a family barn,” he says — and the community parked in the family’s fields. “These were relatively sophisticated marionette shows,” Richards says, ticking off names like The Wind in the Willows and Cinderella.

Richards studied theater as an undergraduate, considering at one point graduate school at the University of Connecticut, which has a renowned puppetry program. “I longed for a career in puppetry for a long time,” he says, “But I got the acting bug in college, so I went for an MFA in acting.”

Richards studied theater as an undergraduate, considering at one point graduate school at the University of Connecticut, which has a renowned puppetry program. “I longed for a career in puppetry for a long time,” he says, “But I got the acting bug in college, so I went for an MFA in acting.”

But Richards says puppetry continues to inform what he does today as chair of the Theater and Dance Department and the director and producer of many of the Academy’s Mainstage performances each year.

“In theater, puppetry is everything — everything on a smaller scale,” he continues. “It’s the all-knowingness — getting into the technical side of things.” The focus on the small and big picture simultaneously helps Richards see the nuances of the plays he produces.

The Laramie Project, which Richards directed in the spring of 2016, is just one example. The play centers on Matthew Shepard, a young University of Wyoming student who was severely beaten and tortured for being gay and who ultimately died.

“I hadn’t picked up on the Matt Shepard story for some reason,” he says. “When I read it, I was devastated. I thought this is the one. I thought it was so relevant to today.”

Richards staged the play like a town meeting, where the audience literally sat among the actors. “Then they could really be a part of it,” he says, noting audience members were even lit up at times.

The theme and story made it a challenging play to participate in, Richards says. “I felt out on a limb. It was definitely risky to do but well-received.

“And it was important for Exeter,” he adds. “I had a cast member who thanked me for changing his perspective on how to see people. That might have been the biggest reward of the whole thing. He was way out of his comfort zone, but he wanted in. He came through beautifully. There was some transformation there.”

That kind of commitment by the students to being challenged is part of what Richards, who has been at the Academy since 1994, loves about his work. “They’re open-minded and so capable on so many levels. Every one of them is a Renaissance person,” he says. “That’s humbling and motivating. I like being a teacher of the imagination and creative thinking — innovation and ensemble — rather than training someone to be an actor.”

While Richards may have felt out on a limb producing The Laramie Project, you can literally find him up in a tree during his time off. For the past three years, he has been building a tree house in the yard of his 1723 house.

The tree house sits among five pine trees. “They have dictated to me how to do it,” he says, noting he is not a fast carpenter. “There are very few right angles.”

Richards uses salvaged goods wherever he can. The windows are made from discarded splash guards from the Exeter dining hall. His most recent project? Laying the floors, using some free walnut flooring he found in front of a house. He’s also on the lookout for a nice thin door if anyone has one.

Richards hopes to finish the tree house soon. His daughters, the recipients (in theory at least), are 9 and 11. But it’s already a haven in a life of busy days. “It’s peaceful. It sounds a little like a ship,” he says. “Even these big pines, they move.”

And the tree house already has some tenants. “The red squirrels think it’s their house now.”

—Janet Reynolds