Nurturing our future

A conversation with children’s book author Gwendolyn Wallace ’17

Gwendolyn Wallace gives children’s literature a new perspective. By centering Black history and Afrodiasporic voices, she says, she hopes to inspire youngsters to “step into their transformative power.”

Wallace draws from her upbringing in Connecticut, visits with grandparents in South Carolina and academic pursuits to seed her plots. She holds a master’s degree in public history from University College London and is in the first year of a History, Anthropology, Science, Technology and Society (HASTS) Ph.D. program at MIT.

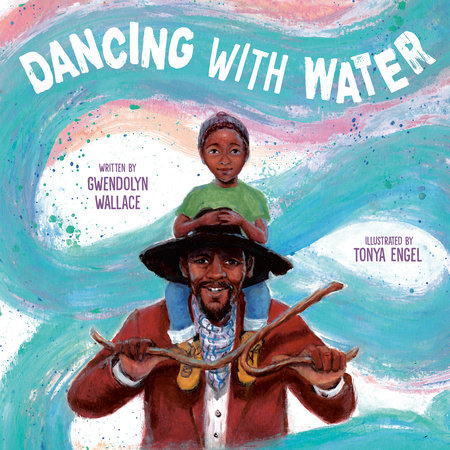

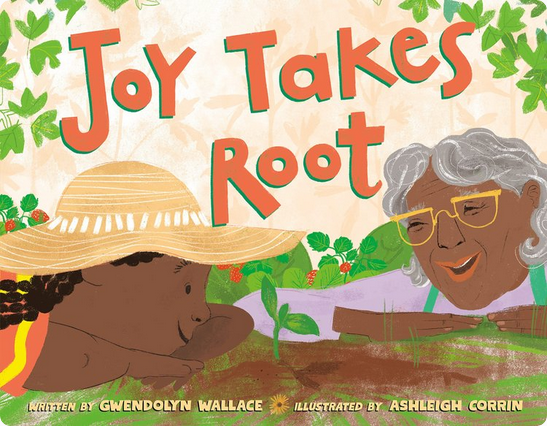

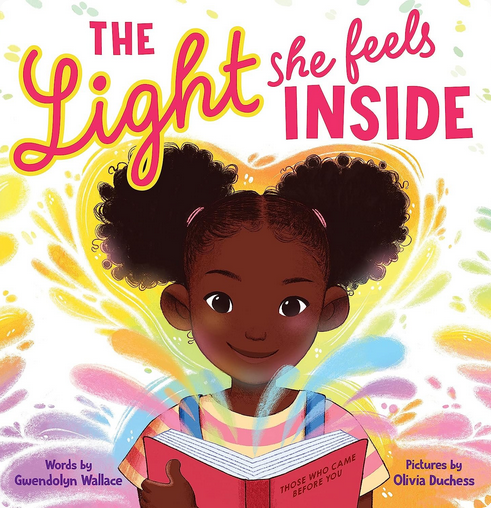

Her book The Light She Feels Inside, published in 2023, offers canny lessons in the history of resistance, name-checking sheroes such as Ida B. Wells, Fannie Lou Hamer, Nina Simone and the Combahee River Collective. In Joy Takes Root, also published in 2023, Wallace portrays a Black grandmother and granddaughter bonding over their mutual love of gardening. Dancing with Water, due out this year, is about the tradition of water divining and opens the door, she says, to conversation about “environmental racism, water protection and water rights.” We caught up with Wallace to hear more about her writing.

You place great importance on representation in stories. Does that drive your books?

I think a lot about what it means for children and adults to see themselves in stories, and it’s not helpful when that conversation begins and ends with visual representation. As a Black woman writing about the experiences of Black children and Black people, my goal is to speak to a distinctly Black mode of living and way of thinking that draws from my experiences. That goes beyond just seeing someone who looks like you: it’s also important that I’m giving children tools in my books, that I’m passing on lessons that I wish had been explained to me when I was 6. I approach writing for children and interacting with them with the understanding that we, as adults, have just as much to learn from them as we have to teach them. I want to hear their vision of the world and let them know that they have a safe place to share that, to combat the messaging telling them that they’re too small or too quiet or too little to have anything important to say.

Dancing with Water, Joy Takes Root and The Light She Feels Inside by Gwendolyn Wallace ’17.

Your first two books feature libraries and gardens. What do those places mean to you?

I wrote Joy Takes Root and The Light She Feels Inside in 2020, and both touch on questions I was wrestling with at the time. I wrote The Light She Feels Inside first, when demonstrations for racial justice were getting quite a bit of media attention, and a lot of people were engaged. I was struck by how artists and writers I was following then were thinking not just about things that we need to get rid of, but also about the excitement and joy and imagination that’s required to build a world after those changes.

I wanted to give that feeling to children, to help them understand that there’s this long lineage of hopeful, powerful and resistant people whom they came from, who dealt with the same feelings, and who found something to do about it; I wanted to say, “None of those things are too far out of your reach.” As a kid, libraries were a safe space — I felt freedom to read and explore — so I wanted to share my love for libraries as imaginative, as generative, as nurturing spaces.

And Joy Takes Root?

That came from the same time frame. I had COVID; I was very sick for many months, back in my childhood bedroom, relying on my parents in a way that I hadn’t since I left for Exeter. I was struggling with exhaustion, fatigue and brain fog, feeling distant from my body. One important thing that helped me get back to that feeling of embodiment was gardening. I spent a lot of time with my hands and feet in the dirt, thinking about my ancestors, thinking about my body, thinking about the connections I feel to plants and animals. My paternal grandmother was an avid gardener; she taught me so much about plants, and how to think about myself in the world. Joy Takes Root is about my paternal grandmother; Ms. Scott, the librarian in The Light She Feels Inside, is named after my maternal grandmother.

Is there a shared thread running through your fiction and academic work?

There’s a topical thread of wanting to connect with the people I came from, wanting to understand Black history, to highlight histories of Black resistance. There’s also this methodological thread: play. When I was a child, I loved to play and make things and try every art form under the sun. As I got older, I lost some of that curiosity, some of that willingness to play. Writing for children, then turning back to my adult writing, helps me keep that playful spirit, that spirit of experimenting and pursuing paths that might not make it into the final draft.

Your Ph.D. encompasses history, anthropology, science, technology and society. Have those areas always been of interest?

I’ve always felt uncomfortable placing myself in one discipline. When I went to Yale and found the Program in the History of Science and Medicine, something clicked, and I thought, “Oh, this is where I want to be, working at all these different scales and time periods, where I get to use lots of different methods and lots of different parts of my brain.”

Was Exeter influential in shaping your worldview?

Exeter introduced me to so many different topics and thinkers that I would not have otherwise discovered at that time. My favorite courses at Exeter were Courtney Marshall’s Toni Morrison and Sydnee Goddard’s Animal Behavior. In Animal Behavior, we were studying mice and mazes, and to have that kind of opportunity before college was amazing. To read and think about a good chunk of Toni Morrison’s work for a semester is something a lot of people don’t get ever in their lives, certainly not until college. Having the chance to think deeply, to walk into every class thinking, “I might not have understood everything that happened in the reading or the homework last night, but I do have something valuable to say about it” — that definitely shaped how I see the world and how I move in it.

Tell me about the new book you are working on that’s due out this year.

Dancing with Water is about the tradition of water divining, that there are people who can sense water underground and dig wells for their community. I set it in the Black South to open a conversation with children about things like environmental racism, water protection and water rights. The main character, Kit, is nonbinary, and learning this tradition from their grandfather. It’s also a story about gender fluidity and what it means to feel safe in your body, learning something that is being passed down to you, something that is yours.

And you have another title, about pioneering Black science fiction writer Octavia E. Butler, coming out in 2026.

Yes. Imagine New Suns will be the first picture-book biography of Octavia Butler, which I am honored to have had the opportunity to write — and sad that it took this long for her to have a picture-book biography. I didn’t learn about Butler until I was in college. If I had learned about her earlier, about her use of experimentation and play, she would have been another person that I could have seen myself in.

— Daneet Steffens ’82 is a books-focused journalist. She has contributed to the Bulletin since 2013.

This article was first published in the winter 2025 issue of The Exeter Bulletin.