Walking in the footsteps of soldiers

Empathy deepens relevance for students researching the Civil War in a new Exeter Innovates course.

Students in "A People’s War: Digital Humanities in the Study of America’s Civil War Era" gather at a monument to solders from the 20th Maine Regiment.

For the 12 students enrolled in A People’s War: Digital Humanities in the Study of America’s Civil War Era, channeling the lives of Civil War soldiers has led to unexpected discoveries: a searing sense of loss still evident in long-ago handwriting, the emotions of a young farmer forced to fight brutal battles, the pain of public shaming reserved for those shot in the back.

Working with the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg and Gettysburg National Military Park, these students have become contributors to the Killed at Gettysburg project, a collaborative venture that aims to aggregate thousands of stories from the 46,000 estimated battle casualties. The project’s goal is to collect data, one soldier’s story at a time, that researchers can mine for decades to come.

In the coming weeks, each student will write narratives about soldiers from two New England regiments: the 5th New Hampshire and the 20th Maine. Watch for their stories at the project website, killedatgettysburg.org.

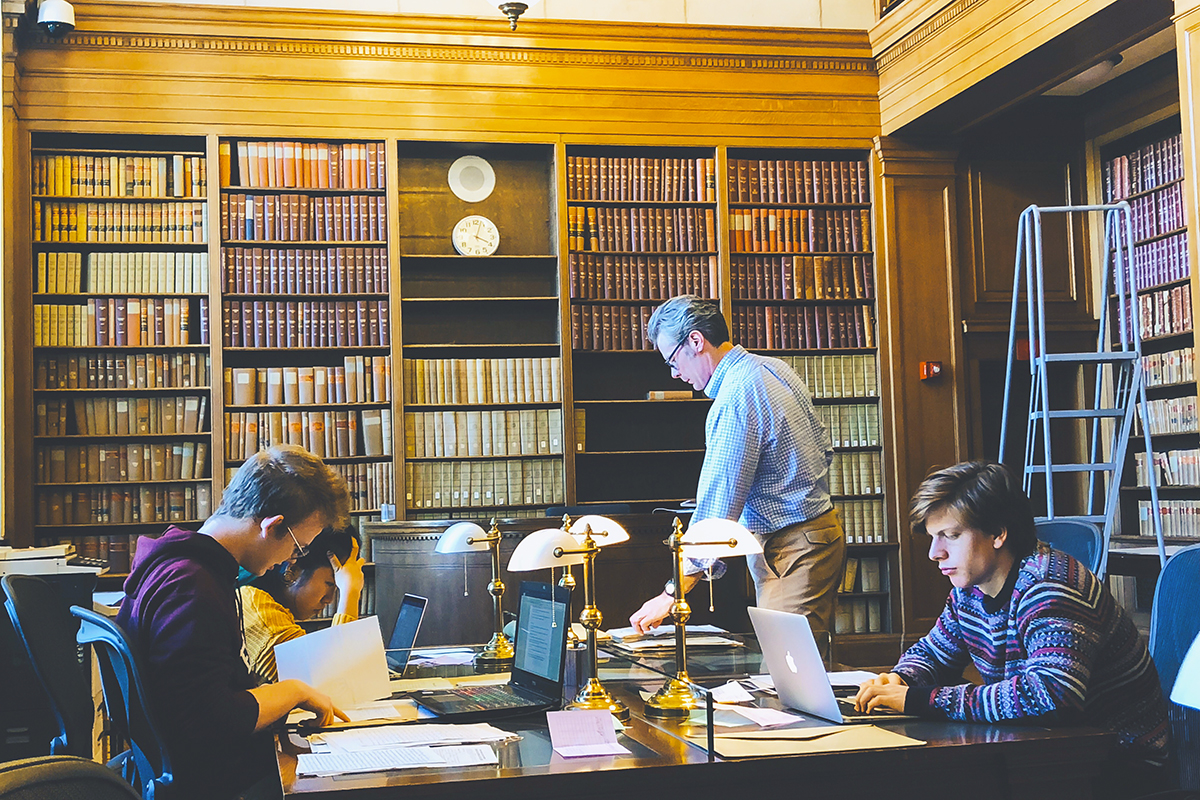

We met with the students and History Instructor Kent McConnell, who developed this new course, to discuss their spring break trip to Gettysburg, Antietam and the National Archives. Below are edited excerpts from the conversation that took place in Elm Street dining hall.

Q: You are each in the process of developing narratives about two soldiers who died at Gettysburg. How did it feel to be on the battlefield, literally walking in their footsteps?

Jane Collins ‘19: On the battlefield, some of the students pointed to rocks. “That confederate soldier was standing behind that rock when he killed this guy.” We had a direct view, as if we were the solders, a bird’s eye view instead of looking at maps.

Marie Leighton McCall ‘18: Hearing those stories – that man stood right here. That really resonated.

Harry Saunders ‘18: A lot of these soldiers were our age. That was a big thing for me. … I spent a lot of the time thinking, wow, could I have charged? What type of atmosphere do you have to be in to make you do acts of war? They were really just kids.

Chi-Chi Ikpeazu ‘18: The soldiers were our age, walking across the battlefield, and they fought during the summer. OK, I do sports. Walking across the battlefield with how many pounds of armor and trying to encourage myself even though I might die in a couple of seconds? Those aren’t equal. It was nearly impossible to equate myself to the solders, but at the same time it was so possible because these people were individuals, not just part of a huge machine that fought 150 years ago.

Q: Can you talk more about how these connections with your subjects were forged?

Wendi Yan ‘18: Before we went on the trip we had already done a whole term of research. Knowing that context helped a lot with feeling a connection. … When we went to the National Archives we were saying – this is my soldier.

Kent McConnell: You are pointing out a linguistic shift to “these are our men.” I think that linguistic shift was really important: this personalization of history, where you can understand it a little more deeply.

Saunders: When you’re at the National Archives reading a letter signed by the guy who wrote it, realizing these are his genuine thoughts: It’s a wow moment. Like being on the battlefield walking where they were walking. People were shot where we were walking.

Winslow MacDonald ‘18: One of the solders wasn’t actually killed at Gettysburg. He was shot at Gettysburg, put on furlough and sent back to Maine. There was a backlash. People were saying that he didn’t die with honor because he died three weeks later. I wanted to defend him. Yeah, he was here. He was shot. He died from the wounds that were inflicted on him there.

Maria Heeter ‘18: I was reading the records from a mother who was trying to request a pension because her son and husband had died in the war. She had all these great testimonies from other people that said she’s depressed, she can’t work, she can’t physically get out of bed. Nothing was in her handwriting, it was all other peoples’. But, they needed her to sign one thing, and there you could see her shaking handwriting. She could barely hold whatever she was writing with. I didn’t realize how much you could learn just from the handwriting of someone.

McConnell: One of the things that I was hoping to get out of the project is that, as you get closer to events in the historical past, you see that things could have gone differently at different times. When we look back at the Civil War we tend to mythologize. You learn that Gettysburg and Vicksburg were the turning tide of the Civil War. Well, two weeks later there were major draft riots in New York City. I’m pleased to see you trying to make sense of the granular as well as telescoping back and understanding the broad picture. That’s really important for Americans to understand when we make major decisions about going to war or not. Mythologizing is all part of the story we want students to appreciate for the [Killed at Gettysburg] project as a whole.

Q: This course is one of the new, experimental Exeter Innovates courses. Did it differ from others you’ve taken at Exeter?

Saunders: I’ve always loved history, especially here at Exeter. The reason I liked other classes was because of debating and analysis. This class didn’t feel like that – it felt more investigative. It helped me realize there are still a lot of frontiers of history that haven’t been explored yet.

Yan: I was attracted to the methodology of this class. It’s cool to “live” in a historical period for a while. This was a more independent type of research: more cohesive, comprehensive.

Q: What surprised you most from your experiences in this course?

Heeter: The space and eeriness of Gettysburg and how it impacted me.

Kianan McDonald ‘18: The idea of telling history as the story of an individual. It’s very subversive to this more mythological view of history where you have grand forces doing this or doing that. Individual history is a way to counteract that to get a completely, wildly different view on historical events.

Yan: I struggled with how much truth I could actually find. It made me wonder how, even when you’re doing a lot of research, there might be a whole different story behind it. And maybe you’ll never be able to find out.

Saunders: Just how slow and hard historical work is.

Ikpeazu: I really respect research now.