Six questions for Ilya Kaminsky

Daniel Zhang ’22 asks the Ukraine-born poet about politics and poetry, writing in a foreign tongue, and tips for young writers.

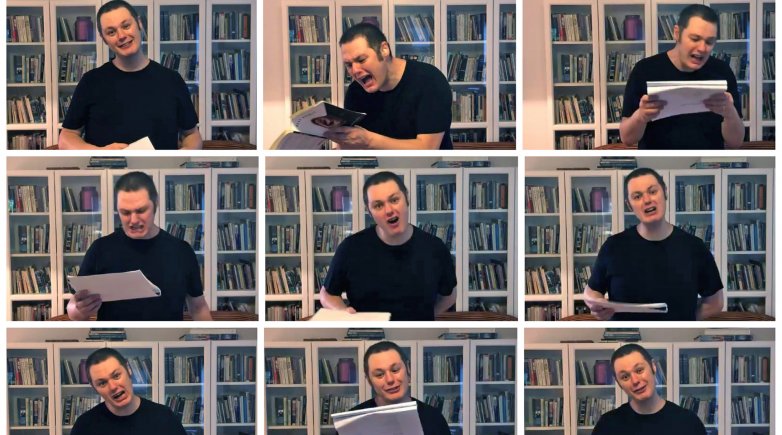

Images from Kaminsky's reading of poems from "Deaf Republic."

Ilya Kaminsky started off this year’s Lamont Poetry series with a reading that was vivid with passion. His Q&A with students, held the next day, was energized both by Kaminsky’s natural warmth and the students’ eager questions. Perhaps not surprising for this poet whose latest book, “Deaf Republic,” led the BBC to name him one of the “12 artists that changed the world in 2019.”

Described as a “two-act play in which an occupying army kills a deaf boy and villagers respond by marshaling a wall of silence as a source of resistance,” “Deaf Republic” has direct ties to Kaminsky’s own life as a Ukrainian immigrant to the U.S. who lost his hearing at the age of four.

One of the students strongly affected by Kaminsky was Daniel Zhang ’22, a poet himself and frequent contributor to The Exonian. Zhang “sat down” with the author via Zoom for a wide-ranging conversation. Below are lightly edited excerpts from that interview.

You chose to write “Deaf Republic” in English as opposed to Russian, your native language. What transforms for you personally when you write poetry in English?

I came to the U.S. when I was 16, and I was still writing in Russian for a while.

My father passed away, and he was the person who taught me poetry to begin with. And so it felt weird to write Russian about the death of the person who taught you the language. It felt like, "What am I doing? Am I making art out of this?" And I decided, maybe mistakenly, "Well, maybe some of the poems I write might help my family because it's such a personal subject."

But if you're a poet, you don't really have a choice. You have to write. And so English provided this kind of escape, if you will, because nobody in my family could read English and I didn't really know [English]. I had just come to America. … We came to [the] U.S. in '93 and he passed away in '94.

So it was a private language, and I liked that it was. It felt interesting to have English just for myself, to be in the same room with English and nobody else in that room. The language, I thought, had a home for a certain kind of grief.

You have a very distinct reading style, one that's very expressive and varies greatly in tone, inflection and volume. Is that a public performance or is that a private act for yourself as a poet?

I'm one of those people who like to revise a lot and who believe that revision is really the heart of the writing process. Revision is what makes writing new and fresh and interesting. But once you publish a book you can no longer revise the poems.

Well, that's not imaginative! You can still revise it in your rhythm. You can change line breaks. You can change emphasis. You can change momentum. And that is what makes it interesting for me, the reading itself. Otherwise, it would be something that I do over and over and over again.